RSF SOCIAL FINANCE AT A GLANCE

Location: San Francisco, CA

Founded: 1936

Employees: 35+

Structure: Nonprofit

Clients: 1,700+

Impact: $275 million+ in loans and over $130 million in grants have been made since 1984

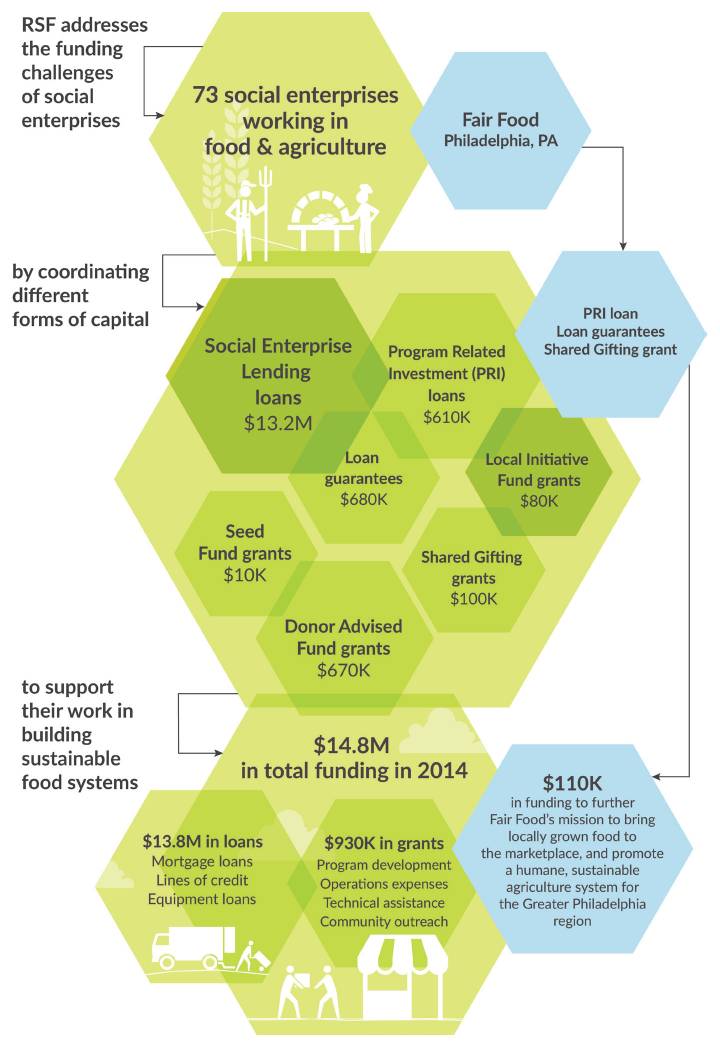

In short: Financial services organization, including a social investment fund and a program related investing fund, that provides low-interest loans and grants to for-profit and nonprofit institutions that serve a social or environmental purpose

Founded in 1936 as the Rudolf Steiner Foundation, San Francisco-based RSF Social Finance is a nonprofit financial organization dedicated to transforming the way the world works with money. RSF’s mission is to transform the often complex, opaque, short-term focused, and anonymous nature of the financial system into a world where financial transactions are direct, transparent, personal, and based on long-term relationships. No small task. At the helm of this effort stands Don Shaffer, who has been president and CEO since 2007. We sat down with Shaffer at his office in the Presidio to discuss shifting the paradigm of the financial industry and what companies typically need to scale successfully.

How did you develop the three focus areas that RSF typically concentrates its investments on?

Don Shaffer: We focus on food and agriculture, education and the arts, and ecological stewardship. These came directly out of the work that Rudolf Steiner did in the early 20th century in Eastern Europe. He was a philosopher, scientist, and all around Renaissance person. The brand-name things that Rudolf Steiner brought to the world are Waldorf education and biodynamic agriculture, but he also made contributions to architecture and economics. The founders of RSF read his lectures on economics from 1922. Just as a biodynamic farmer looks at his or her farm and soil in a holistic way, or as a Waldorf schoolteacher looks at his or her students and school in a holistic way, we’re trying to look at money in a more holistic way.

How do you assess the impact that you can expect from an organization when you are deciding whether or not to invest? What are your criteria for your investments?

DS: We lend money to both for-profits and nonprofits. Our portfolio consists of a $100 million loan fund, which is our primary vehicle for putting money out in the world. Half of the social enterprises we lend to are for-profits and half are nonprofits. The primary thing we’re looking for across the board is, do these organizations have a social or environmental purpose as their primary reason for being, such that they would not be in business but for the environmental or social issues that they’re helping to address?

We use the B Impact Assessment Survey as one way to determine and benchmark an organization and its practices. But in addition to that, we have a much more qualitative, relationship-oriented methodology that we’ve developed over 30 years that looks at the intention of the management group and the business.

That’s the very first thing that we look at. A business that we’re looking at may be phenomenally profitable and any bank would want to lend to it, but we don’t even look at it until after we’ve looked at the social or environmental piece. And it can’t be something simple like using organic ingredients. What we’re looking for is a holistic commitment to harnessing business as a force for good. We’re looking at whether the business is an advocate for change, for example, and not just that it’s doing something that happens to coincide with a positive trend in the marketplace.

What is the rationale behind dedicating half of your portfolio to for-profits and half to nonprofits? Are the terms of the loans the same for each type of organization?

DS: It wasn’t until 10 years ago that we started actively making loans to for-profits. In the early 2000s we sensed that there was a growing number of values-aligned business enterprises that we also wanted to lend money to. We’ve gone from 100 percent nonprofits to 50 percent nonprofits only in the last 10 years. In not-so-distant future, I think that more of our funds will be going to for-profits than nonprofits.

The terms of the loans do differ. We make mortgage loans or construction loans to nonprofits such as schools. These are asset-backed loans, and so they typically have five-year terms and the non-profits typically get the lowest base interest rates that we offer. For the for-profits, we’re more often doing lines of credit, accounts receivable financing, or inventory financing, all with rolling one-year terms. They pay our base interest rate plus some kind of risk premium based on how risky we think the loan is.

Can you explain RSF’s business model?

DS: We have approximately 1,700 investors in our loan fund and they expect to receive their money back plus a relatively small return. Historically the return has been 3 to 4 percent, but right now it’s lower because interest rates are lower. People think of it like a bank CD because you can put your money here and take all or a part of it back out every three months. So it’s fairly liquid in that respect, and it’s very low risk – we have 100 percent repayment rates to our investors in the last 31 years and we intend to keep that up. We use the funds that are invested by the investors to make loans to about 90 borrowers. Our loans are between $250,000 and $5 million, with an average around $800,000.

Our special sauce is that we do a very good job at assessing risk so that we can make sure we get our investors’ money back. We also do a good job at being catalytic in the sense that many of the organizations that we fund would not be able to get a bank loan because they’re either too early-stage or they’re too hard to understand. For example, when Revolution Foods came to us for a loan, I don’t think anyone else in the Western Hemisphere would have made a loan to them at that time, because it was just a little too early and it was just a little too hard to understand the business model. And now of course the company has done phenomenally well and is backed by a very large bank. That’s a common story for us.

Does RSF only make loans or do you make equity investments as well?

DS: Our core competency is direct lending. On occasion we make direct equity investments but not out of the same pool of funds. We also have funds that are philanthropic in nature. In many ways we’re kind of like a bank and a foundation combined, but the large majority of what we do is just lend money.

What sort of trends are you seeing in impact investing?

DS: Certainly the advent and advancement of B Corps has been a huge trend that we’re fans of because it allows people to know the standards by which a social or environmental purpose organization is working. I think that on the investment side there are many, many more socially conscious investors who want to go beyond just removing certain stocks from their public equities portfolio and want to do more direct investing in social enterprises. It’s a very exciting time. I don’t see it as a fad — I think it’s a long-term trend that could eventually change how markets operate in general.

What’s concerning you most about the traditional finance system right now?

DS: I have lots of concerns about the traditional finance system, so I’ll have to do the short version. Rampant short-termism is a big problem. The domination of the capital markets by a handful of gigantic banks is a problem. The opaque nature of the banks’ business models is a problem — they prefer that most people not ask too many questions about how they make money. Of course, another big problem is that those banks have many, many shareholders who want the banks to do well. It’s this perverse thing where we’re all complicit in the big banks getting bigger because we own shares of their stock and want them to do well, and meanwhile they’re out there systematically crushing all the small guys.

The good news is that more people are asking more questions. Just as the local food movement has encouraged a lot more transparency and encouraged people to ask where their food comes from and what the ecological conditions are like, people are now starting to look at capital and where they get their funds for their business as a fundamental ingredient in their business. We’re seeing more companies coming to us saying that they’d like to be to part of the RSF community because they really don’t believe in Bank of America or Citigroup, for example. They want their funds to be aligned with their business values in the same way that their organic, fair trade ingredients are.

How do we shift the paradigm within the financial industry to avoid these sorts of problems?

DS: One way is through crowdfunding. There are now ways for both accredited and non-accredited investors to get involved with financing inspiring social enterprises in their regions. If you’re interested in making a direct investment in an organic food company in your region, there are more ways to do that today than there ever were before.

I’m not a big believer that top-down policy change is going to be effective. Real changes are going to come from the grassroots awareness and consciousness shift that is happening right now. The way for those changes to happen fast and in the most lasting way is for people to actually get involved with direct investments or direct loans. Even if it’s a small amount, $100, $500, or $1,000, there are ways to do that today that you couldn’t do 10 years ago, which is really exciting.

Can you tell us a story of one of RSF’s investments that really sticks out to you and epitomizes what RSF does?

DS: Common Market Philadelphia is the first one that comes to my mind. Haile Johnston and Tatiana Garcia-Granados are two social entrepreneurs in Philadelphia who started a local and organic food distribution business because they sensed that small family farms in the Philadelphia area were not able to find a reliable market beyond farmers markets and the people who support CSAs . Perhaps more importantly, they sensed a huge need for healthy and nutritious food, particularly in the inner-city areas in Philly at schools and hospitals.

Common Market has had a classic David and Goliath story. It had to go up against much bigger entrenched distributors just to get a toehold in with the big institutional buyers. It has done a phenomenal job, and now Common Market owns a building in North Philly and has created something called the Philly Good Food Lab, which is supporting sustainable agriculture enterprises throughout the whole greater-Philadelphia area. It will soon be opening a Common Market Atlanta, and it is helping literally hundreds of other entrepreneurs who are starting food hubs and local organic food distribution businesses in other parts of the country. I think that there are about nine levels of impact and transformation that Common Market is creating, and the fact that we were able to help it using several different kinds of funding, none of which it could have gotten in one place from another investor, is really satisfying.

When did RSF step in, and how did the capital you deployed help Common Market grow?

DS: We made a $130,000 line of credit available to the company, before anyone else would have done that. That line of credit has since tripled. Eventually, the company outgrew its warehouse and it really needed a building. There was a building in North Philly available, and it really took a team effort to help the company make that purchase. Several foundations provided partial loan guarantees that enabled us to get comfortable with the risk so we could make the loan.

We also provided technical assistance by helping the founders broker the deal for buying a million-dollar building. We provide a lot of technical assistance to the companies and organizations we work with, because many of them are light in the area of finance and are not used to figuring out how to structure a million-dollar purchase with a loan; they’re used to figuring out how to get really good, healthy, nutritious local organic food from point A to point B. So we really have a multipronged story of impact and the ways that we help companies grow.

“Many of these investors want to have a direct connection with their investments and feel that their investments are having social and environmental benefits, as opposed to just being less bad. I think this is going to have tectonic effects in the market.”

What advice do you have on making sure that the mission and vision stay with a company as the company grows and scales?

DS: You really have to interview your funding partners in a much more rigorous way than I think most entrepreneurs do. Sometimes you’re in that position — and I’ve been t here — where you’re desperate for funds and you’ll say whatever you feel like you need to say in order to secure those funds from whomever you can. I understand that pressure, but the way you need to look at it is that you’re interviewing them as much as they’re interviewing you. You absolutely have to make sure that there’s really strong alignment between your intentions and their intentions. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen the funding process happen too quickly, and not enough of a relationship gets established and then sometime down the line there are a lot of problems and emotional turmoil because it turns out that your funder had a little different idea of what was going to happen.

What have you learned from failure, either personally or professionally, that has served you well in your career?

DS: The key thing about failure is to do an honest post-mortem. Failure is not necessarily a badge of honor that is going to help you succeed next time. But if you can really dig into the parts of the failure that had to do with you as a human being and figure out what you need to learn and how to learn it, and if you make a plan and find some mentors rather than rushing out again and trying to be a hero, then failure is valuable.

What is giving you hope for the future?

DS: I think there are an increasing quantity and quality of social entrepreneurs who are harnessing the power of business to good, and thankfully there are an increasing number of investors who want to fund them. Many of these investors want to have a direct connection with their investments and feel that their investments are having social and environmental benefits, as opposed to just being less bad. I think this is going to have tectonic effects in the market. I think within a generation, nearly all companies will be Benefit Corporations or something equivalent.

3 TIPS FOR MISSION-DRIVEN ENTREPRENEURS

1 BE TENACIOUSLY PERSISTENT

For aspiring social entrepreneurs, I think that tenacious persistence is the most important thing. There will be all kinds of rollercoasters that you’re going to ride in the early stages of the organization, so you just have to be mentally and spiritually prepared to overcome them and bring as much creativity to them as you possibly can.

2 TAKE TIME TO FIND ALLIES

Finding allies and peers, who may or may not have a direct stake in the outcome of your enterprise, is critical for support and for new ideas, even though you’ll feel like you don’t have time for it.

3 BE OK WITH A NON-LINEAR PATH

There is a lot of pressure in our culture to have a linear career path. I’ve had a very non-linear career path and I would urge entrepreneurs who are trying to do good with their business to feel that that is OK and not to be apologetic about not having a linear career path. Having different types of experiences and learning adds to your resiliency as an entrepreneur and gives you a much wider lens.