That’s the idea behind a crop of startups that are borrowing the tools of Silicon Valley to create a true digital sharing economy. Many of them are structured as cooperatives — democratically owned and governed organizations. But they all seek to treat workers more fairly and allow them to share in the fruits of their labor. Think of them as Fair Trade apps. Here are some to be on the lookout for.

1 RIDEAUSTIN

After Austin residents voted for more stringent regulations on ride-hailing services in May of 2016, Uber — along with Lyft, its smaller rival — abandoned the city. That has prompted a host of new startups with more driver- and community-friendly services to take their place. One of those is RideAustin, a nonprofit ride-sharing company that began phasing in service in spring of 2016. As a nonprofit, the startup vows to work with the city and share data to help improve transit planning. And the app allows customers to round their fares up to raise money for local charities that will include free and reduced-rate rides for low-income elderly and disabled citizens.

2 JUNO

// gojuno.com

Juno is a new ride-hailing service that opened for business in New York in 2016. It’s not a co-op, but co-founder and CEO Talmon Marco has called it “an ethical, socially responsible ride-sharing service.” Marco is betting that by treating workers better, he can attract the best drivers and take market share from Uber.

Juno takes a 10 percent cut from each ride, compared with Uber’s average commission of 20 percent. It also provides smartphones to drivers and pays for their data, and plans other driver-friendly features such as 24-hour support and the ability to block riders.

And unlike Uber, ownership of which is closely held by its founding team and investors, Juno has pledged to put aside half of its founding stock — or a billion dollars’ worth — for drivers. The shares will be awarded to drivers who work for Juno full-time or close to it, and drivers can earn more shares the more time they put in driving for Juno.

3 FAIRMONDO

If Etsy were owned by its crafters and buyers, you might begin to get something like Fairmondo. Based in Berlin, the site is a digital marketplace for sustainable and Fair Trade products from smartphones that are ethically manufactured with conflict-free minerals to organic clothing. Since it launched in 2013, Fairmondo has attracted 15,000 users, including 2,100 members, each of whom buys a 10-Euro share in the company. In addition, it has raised funding through two successful crowdfunding campaigns.

Now Fairmondo is looking to expand globally through a network of co-ops in different countries that are independently run by locals in their native languages. Next up: the UK, followed by the US sometime in 2017. “Fairmondo is to me a big experiment to create a new model of multinational corporation, which is transparent, decentralized, and democratically owned by its local stakeholders,” says founder Felix Weth. “As a marketplace, Fairmondo will hopefully help other good businesses reach customers who care for the future of their children.”

Stocksy’s Victoria offices. Photo: Jeffrey Bosdet, Page One Publishing

4 STOCKSY

// stocksy.com

One common complaint of creative workers in the digital age is that their work is being commoditized. From musicians to artists to writers, the freewheeling internet has driven down prices — and morale. Enter Stocksy, a stock photography site based in Victoria, British Columbia. Unlike other stock photography sites, it is owned and governed by its photographers and employees. At Stocksy, photographers keep up to 75 percent of revenue, compared to 15 to 45 percent at most sites. And the company distributes 90 percent of its profits at the end of each year among its photographers. That has helped it attract more than 900 photographer-members around the globe. Stocksy’s staff are also owners.

5 COOPIFY

In recent years, domestic workers have banded together to create cooperatives to control their destinies. Now a new app is helping the co-ops expand their presence into the digital sharing economy.

The app, called Coopify, was dreamed up by the Robin Hood Foundation, a nonprofit that fights poverty in New York, and the Cooperative Development program of the Center for Family Life, a social services organization. The two organizations approached students at Cornell Tech and challenged them to create a digital platform that could benefit low-wage workers.

The result, Coopify, will allow customers to book services with organizations like New York’s Si Se Puede! Women’s Cleaning Cooperative and Golden Steps, a co-op of elder care workers. The students at Cornell Tech worked closely with co-op workers to create an app that reflected their needs, including multilingual support and SMS text messaging for those without internet access or smartphones. Coopify is being beta-tested by the cooperatives and is expected to launch publicly in January 2017.

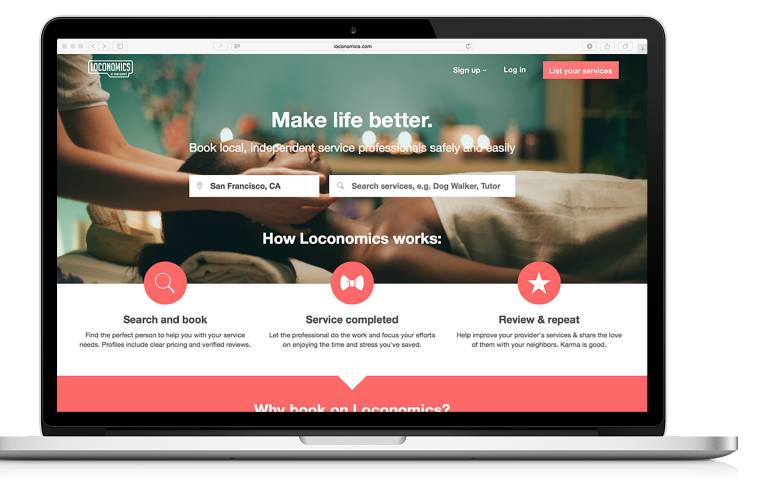

6 LOCONOMICS

Josh Danielson got his first taste of the sharing economy when he began renting out his San Francisco apartment on Airbnb to help cover the rent while he was in business school. He realized the power that flowed to the booking platform owners, and decided to create a more worker-friendly version. The result: Loconomics, which launched over the summer of 2016, is like a digital cooperative for all sorts of freelance professionals, from web designers to masseuses.

The freelancers pay an annual membership fee that gives them access to the site’s tools, including software to post a profile, manage bookings and payments, and see customer reviews. They also receive a stake in the company and a vote in its management. Danielson worked with the Sustainable Economies Law Center on the co-op’s bylaws. At press time Loconomics was operating only in San Francisco, but plans to expand to other parts of the country.

Amy Cortese is a New York-based journalist who writes about topics spanning business, finance, and food. Her book, “Locavesting,” was one of the pioneering works on the emerging local investing and community capital movement. More recently, she founded Locavesting.com, a media and educational site that covers this evolving financial landscape. Follow her on Twitter: @Locavesting.