Adapted from “High-Hanging Fruit: Build Something Great by Going Where No One Else Will” in agreement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Mark Rampolla, 2016.

TURNING ON THE IDEA MACHINE

In the winter of 2003, I was a young mid-level executive with International Paper and so bored that I wondered what I was doing with my life. The truth was that I had thought a good deal about joining a startup, probably as the general manager or CEO who took over from an entrepreneur with a brilliant idea. Over the last 10 years, I had become confident in my business skills. I was the guy who could build and lead teams, develop strategies, execute plans, reach goals, get things done. I could see myself taking a company from $1 million to $10 million, or $10 million to $100 million, or maybe even $100 million to $1 billion. But in those dreams, I never cast myself as the founder, the person who had come up with the new idea.

Then a good friend said something simple that hit me like a lightning bolt: “The only difference between you and an entrepreneur is an idea, and you are as capable as anyone of coming up with one.” Why had I been telling myself that I wasn’t creative or smart enough to come up with an idea? With my friend’s simple observation, a switch flipped in my brain, and I couldn’t turn it off even if I wanted to. I suddenly couldn’t stop thinking of new business ideas. I was an idea machine.

EVALUATING THE OPTIONS

My wife Maura was happy that I was feeling so energized and excited. Of course, I knew that whatever business I pursued, I needed and wanted full buy-in from her. So one evening, a couple of weeks into my manic brainstorming, I brought out my ideas notebook. She read aloud idea after idea: consolidating the dairy industry in Central America, shopping malls in Honduras, clothing manufacturing in Colombia, ecotourism in Costa Rica, exporting chocolate from Belize, trucking. “I don’t want to squash your excitement for becoming an entrepreneur,” she said, “and I have no doubt if you decided to launch one of these businesses you could succeed. But if we’re going to mortgage our lives to launch a business, it needs to be something we can both be passionate about. What about having fun, traveling to great places, making a positive impact on the world? Where does that fit into any of these ideas?”

I looked back at my list, scanning it for ideas by which I could redeem myself. As moneymaking business ventures, I could make the case for all of them, but I could now see that they were hollow — and might lead me and us to the same exact unfulfilled spot I was in now. Maura was reminding me that the right idea had to have a motivation deeper and higher than just typical business success and money.

BRAINSTORM BETTER BY ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

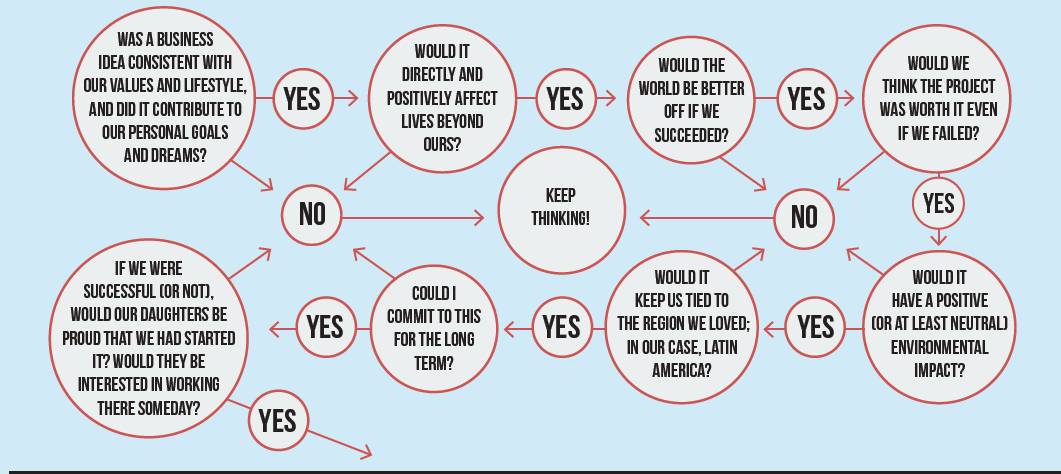

After a few weeks of dreaming and reflecting together, I was ready to revisit business ideation from quite a different starting point. Instead of brainstorming potential gaps in different industries, I made a list of screens, worded as questions, by which I could filter out business ideas that would not have a chance of passing what I started to call the “Maura test.”

PERSONAL SCREENS

First were personal screens, questions that rose out of the conversations we had had on our walks together — our individual values, histories, and interests.

1. Was a business idea consistent with our valuesand lifestyle, and did it contribute to our personal goals and dreams?

2. Would it directly and positively affect livesbeyond ours?

3. Would the world be better off if we succeeded?

4. Would we think the project was worth it even ifwe failed?

5. Would it have a positive (or at least neutral)environmental impact?

6. Would it keep us tied to Latin America?

7. Could I commit to this for the long term? Frommy research I knew that launching a business successfully was a minimumfive-year process and that I’d better be prepared to commit for a decade. Thisproject would very likely define my career and in meaningful ways become myidentity, so I’d better pick carefully.

8. What would our young daughters think about thisbusiness when they’re ten? Sixteen? Twenty-five? Forty? If we were successful(or not), would the girls be proud that we had started it? Would they beinterested in working there someday?

These screens wouldn’t apply to everyone but they werecritical to us, informed by what we had reflected on and determined as mostimportant to us. We were now taking ideation way beyond dairy and trucking.

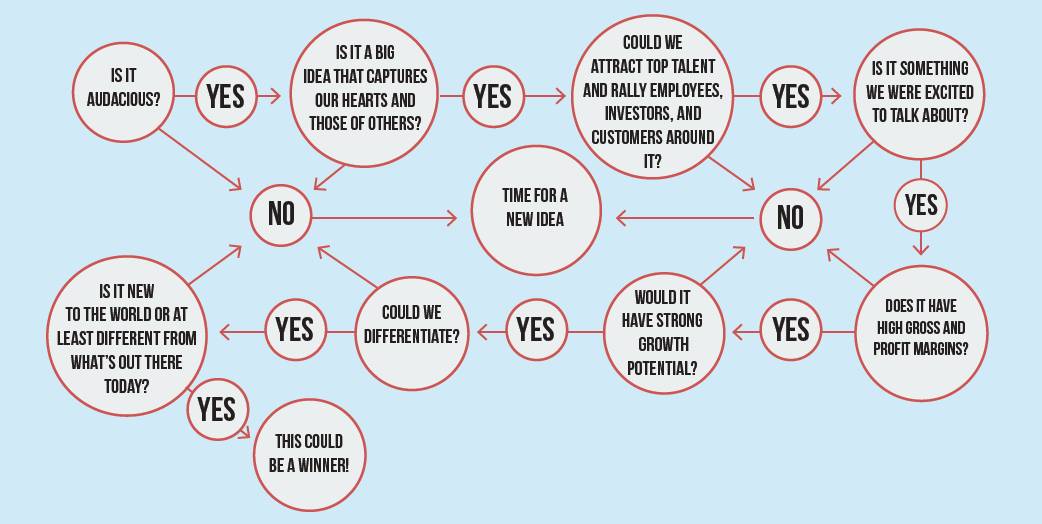

MARKET SCREENS

The second set of screens were classic MBA-style ways to evaluate the potential and viability of a business.

1. Is it audacious?

2. Is it a big idea that captures our hearts and those of others?

3. Could we attract top talent and rally employees, investors, and customers around it?

4. Is it something we were excited to talk about?

If I was going to dedicate a good part of my life to something, why not do something that’s a BHAG (Big, Hairy, Audacious Goal), as Jim Collins says .

5. Does it have high gross and profit margins? I had run paper and packaging businesses with low margins, and I can tell you it’s tough! I wanted to be in a business that had higher margins to work with, which would allow us to pay people well and generate critical cash flow to fuel growth.

6. Would it have strong growth potential? I knew we would start small, but why should it stay that way? It should be something that could grow continuously for years to come and potentially become a billion-dollar business.

7. Could we differentiate?

8. Is it new to the world or at least different from what’s out there today? I realized that the really exciting businesses were innovative, differentiated, disruptive.

CHOOSING COCONUT WATER

With these two sets of screens, we now had a framework to evaluate the many ideas I was generating, which only stimulated more. I compiled all of my ideas in a spreadsheet, and then evaluated them individually against the screens, which gave us context and common ground to discuss them. These screens also helped me avoid suggesting ideas that would never pass the Maura test. Coconut water was on the list from the beginning, but only by developing and using these screens did it eventually rise to the top.

Mark Rampolla is the cofounder and managing partner of Powerplant Ventures, which invests in emerging growth companies that intend to remake our global food system to deliver better nutrition in more sustainable and ethical ways. He was the CEO of ZICO Beverages from 2004 until 2013, when it was purchased by the Coca-Cola Company.