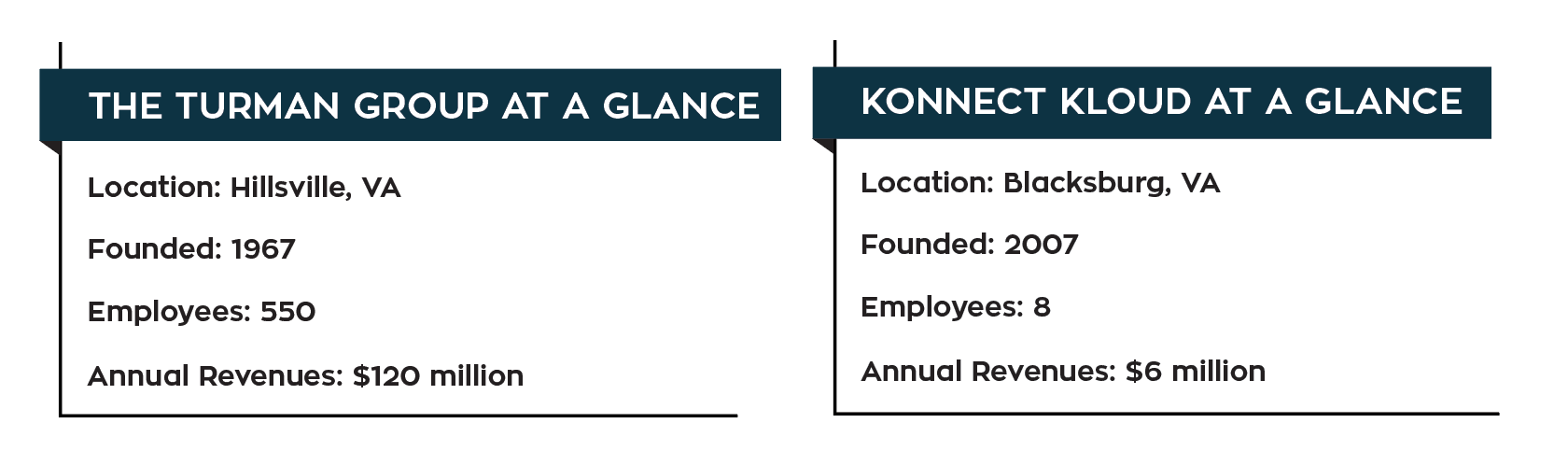

Ryan Turman doesn’t know much about socially responsible, mission-driven, or triple-bottom-line (3BL) business. He’s never heard of impact investing or the localist movement. He’s a George W. Bush Republican — he once had Christmas dinner at the White House — and the heir to one of Virginia’s biggest logging companies, the Turman Group (TTG).

But it just so happens that he and his father run a company that is planting trees, creating local jobs, employing a marginalized group, and offering company ownership to employees. Turman’s latest venture is Konnect Kloud (K2), a cloud-based truck-mapping system that in its proof-of-concept stage alone has already had a major impact on carbon emissions by avoiding 4.5 million trucking miles.

As one of the politically conservative leaders of an extractive company, Turman doesn’t fit many of our preconceived notions of what a conscious businessperson should be like. He’s a white male from a southern, rural, manufacturing community where a main local pastime is hunting. When it comes to business theory, he’s not shy about his margin-before-mission approach. In short, he seems like exactly the kind of businessperson we in the conscious business community are used to seeing — and treating — as our opponent, the evil foil to our better way of existing in the world.

Yet when we consider what TTG has accomplished in boosting its local economy over the last 50 years, and Konnect Kloud’s potential to make a huge impact on reducing pollution and slowing climate change, shouldn’t we wonder what we might learn from the Turman family? Clearly they’re doing something — or many things — right. If we want to truly integrate conscious business into the future of business as usual, those of us at the vanguard of the movement must set aside our idea that political conservatism is anathema to conscious business.

We also need to set aside our personal pride about how superior and socially responsible we perceive our own lifestyles to be. We need to broaden our search for allies and welcome progress no matter what skin it’s in. The future of our work — and our planet — depends on it. And if we take the time to pay attention with an open mind and heart, we may just discover that we are not so different from the Ryan Turmans of the world after all.

Despite the appearance of ideological opposition, several shared tenets run through both conscious business and the business ethic that has allowed Turman to succeed while doing good for his community and other stakeholders.

Ryan Turman (left) with his father Mike, who founded the Turman Group.

An important tenet of conscious companies is their human-centered employment practices. The socially responsible business movement honors, supports, and invests in companies that are building employment access points for undereducated, underrepresented, and previously incarcerated workers. We applaud leaders who dedicate core resources to providing exceptional benefits for their employees. So could we acknowledge TTG for meeting these standards as well, even though its primary revenue stream is harvesting and selling trees?

Ryan Turman explains that his father, Mike, TTG’s co-founder, was always driven by his desire to create jobs. “When my father and a few friends started TTG in 1967, they were focused on keeping the lights on and not going broke,” Turman says. “There aren’t a ton of people falling over to create jobs in southern Virginia. Employing 550 people is a big deal, especially in the rural counties where we work.”

Inclusive hiring

When interviewing job candidates, TTG managers look primarily for strong work ethic. Degrees, criminal records, and past job history mean little — less than 5 percent of the company’s 550 employees have graduated from college. Turman knows that great mechanics, experienced fabricators, and precise lumber graders define how competitive TTG is in a global marketplace. “If you’re prepared to work, then the logical step for us is to find what you excel at and how that fits in,” he explains.

Employee ownership

Shared ownership is another identifier of mission-driven businesses, and the Turmans are excellent at finding the right people to manage and operate individual facilities and business lines. In fact, they’ve been offering employee ownership for more than 40 years, and currently 32 employees have partial ownership in one or more TTG subsidiaries. “Nine times out of ten, the most qualified and loyal employees end up with ownership,” Turman says. “That person realizes the ownership they have represents their savings account. It’s a way for them to get ahead, and it comes with a lot of responsibility. Meanwhile, it’s how we grow.”

Feeding passions at work

Turman also points out that many TTG employees get plenty of unquantifiable satisfaction from their jobs, just as we expect in more obviously conscious workplaces. “Many of the people who cut the forests live in these same forests,” he says. “They camp and hunt and absolutely love being outdoors. They’ve chosen to work in their favorite place, and we give them that opportunity.” Sounds pretty similar to your local 3BL business, does it not?

Yet another similarity between the Turmans’ approach to business and the approach of iconic socially responsible businesses is a long-term sense of responsibility and accountability. Time and time again we’ve seen the destructive effects of short-term business vision: the severely disproportionate ratio of oil creation to oil use, the monoculture cropping on much of the US soil, or the housing crisis of 2008, to give just a few examples. Much of what is broken in our current economy is the result of action taken for short-term gain.

Valuing the long-term

TTG, while considered a conventional business because of the product it sells, has always looked far down the road. “From our standpoint, we’re absolutely social,” Turman says. “Replanting the trees we cut has always been part of the equation. We ask ourselves, ‘What is the need for tomorrow?’” In the last 15 years, the market has moved away from white pine, which will grow back in 20 to 30 years if replanted, toward slow-growing hardwoods like oak, cherry, and walnut. Since these trees need to regenerate on their own, and do so more slowly, TTG is building partnerships with other hardwood landowners to disperse the harvesting burden over more acreage. The company now only harvests 1 percent of its privately owned 22,000 acres every year, and recently set a new goal to achieve complete native species regeneration on its private lands within 40 years.

Reduce, reuse, recycle

In addition to land stewardship and ecological health, recycling is also critical to TTG’s business. “Every form of waste in a supply chain will result in an economic and social cost,” Turman adds. “The lumber industry is no different. Sawdust that isn’t being recycled as a heat source for lumber kilns will lead to the unnecessary burning of fuel and a deflated bottom line.” Since 1997, TTG has recycled 100 percent of its sawdust to heat kilns and produce residential heating pellets.

Turman — a Republican — has launched a new venture that could reduce pollution in the shipping industry.

In the world of traditional business, the word “win” earns attention. In the world of socially responsible business, however, it’s really the phrase “win–win” that sparks interest. The idea that a business owner can win while their employees, suppliers, and investors are also winning is the crux of this movement’s work. The 3BL community views profit as a complex web of financial return, employee satisfaction, societal improvement, and environmental protection. Instead of buying into a “scale” economy in which one side has to go down for the other side to go up, the mission-driven business model suggests that a “web” economy could work better — one in which all components are interconnected on the same horizontal plane. New conscious companies are now emerging with business models based on win–win mechanisms, and Turman’s newest business, Konnect Kloud (K2), is no different.

Konnect Kloud’s win–win model

K2 is an online database that matches import and export truck loads to create a more efficient transportation system. It developed out of a need Turman identified within TTG. “Producing great lumber products was only half the battle,” he says. Getting those products halfway around the world, into a global market, became the project of the second generation of Turman businessmen. “Our initial challenge was geography,” Turman explains. “We were 300 miles from a port and we couldn’t compete because of trucking costs.” So TTG reached out to a few neighboring importers and asked if it could use their empty containers to send TTG’s goods to port. The truckers increased their revenue and both shippers reduced their trucking costs. TTG’s lumber products then became viable in the global marketplace.

“The initial goal was to match seven containers a week,” Turman says. “After we surpassed that, the logical next step was to do the same thing for other companies. We were blown away by how many containers were going in and out of ports empty.”

Thus K2 was born, as Turman saw the incredible opportunity (and the incredible waste) in the intermodal industry. Under current practices, the average shipping container will spend 56 percent of its life empty: importers receive full containers from a port, but send back empty ones; conversely, exporters send full containers to port but receive empty ones. This antiquated system costs the US import/export industry $16 billion annually in wasteful truck trips simply to reposition empty containers. By matching up neighboring importers and exporters to share the same truck, K2 helps two trucks driving four legs become one truck driving two or three legs. “It took us five years to refine a manual process,” Turman says, “and then we started to build Konnect Kloud as a platform that allows any person in the international shipping community to match a container.”

K2 is solving a very real need, and in using the platform nobody loses and everybody wins: trucker drive-time goes down 40 percent while pay increases 15 percent; shipper costs go down 25 percent while per-mile earnings increase 35 percent; and best of all, every trucking-trip match that K2 facilitates eliminates a cubic ton of carbon emissions from our atmosphere.

Turman’s first case study, with Lowe’s in 2015, generated remarkable results, avoiding 216,000 truck miles by matching more than 350 import and export trucks. Now West Coast port shipping communities are very interested in the technology: last year Turman started discussions with a leading national environmental group to launch a California pilot of K2 in response to Governor Jerry Brown’s 2015 executive order setting an aggressive carbon emissions reduction target. If he is successful in scaling the company, Turman expects K2 can further reduce carbon emissions tenfold in the next two or three years alone. This sort of across-the-aisle partnership is the exact relationship Turman needs more of as he looks to launch similar pilots in Charleston, SC; Norfolk, VA; and Savannah, GA.

The beauty and elegance of K2 is that importers, exporters, dispatchers, and truckers now have a platform for collaborating on their own. As adoption of container-matching grows, everybody wins, and not just from a revenue, wellbeing, or emissions standpoint. The shipping logistics community is now being connected in a more efficient way than ever before. And as this traditionally Boomer-led industry transitions into Millennial leadership hands, we can expect greater innovations in the coming years. What many call one of the dirtiest industries could have the greatest opportunity for cleaning.

K2’s partnership with environmentalists is a perfect example of the business relationships we risk losing by overlooking partners because of our own stereotypes. Turman’s key to success, in many ways, has been his ability to ask for help and organize not just his colleagues but his competitors and opponents as well. In an ironic twist of fate, TTG, K2, and leading environmentalists are all connected now and moving into the web economy together. This unlikely partnership demonstrates that the most fertile ground for progress is often far from the world of black-and-white thinking.

As Turman scales K2, he says he will consider becoming a Benefit Corporation. However, after bringing six previous products to market and leading business development for a $120-million-a-year company, he also knows that you only have 168 hours in a week. “There are only so many things you can focus on,” he says. In the end, he wants K2 to be a profitable company even more than he cares about the formal hoops and certifications of the conscious business community. But that’s not because he doesn’t value mission. Turman echoes something I’ve heard countless conscious CEOs say: “A successful company is in the best position to have the biggest impact on the greater good.”

So this is where the rubber meets the road. Donald Trump is our president. All of a sudden, the mission-driven business community stands faced with one of the most impactful choices of the decade. Do we dismiss the work of someone like Turman? Do we dismiss his values? Or do we acknowledge his innovative achievements through awards programs, give him access to impact capital, and connect him with advisors who could help him scale K2, like we would with a typical emerging and innovative B Corp?

A broader idea of diversity

This is where we must stare hard at our own values. It’s a frightening moment, not just because of what changes we might dislike, but because of the power we have gained thus far and the opportunity that is now before us. We have the potential to become a force for good, not just in business but in the world at large. We cannot, however, be champions of diversity and inclusion if we are only willing to include individuals diverse in appearance but not in point of view. If we want the world to be more accepting of those with varying sexual and gender preferences, for example, let’s also do our part by being more accepting of those with varying tax policy preferences, for example. We need to welcome great ideas no matter where they come from — and fast.

It’s time for conscious capitalism to cast a much wider net than we ever thought possible before. We need to be engaged in the principles and detached from the personalities. We need to evaluate ideas, programs, and collaborations with a newly refined objective fervor.

It’s now or never for expanding conscious business leadership

This year marks a new frontier for the 3BL movement. Business as a force for good is rapidly becoming mainstream, and a serial entrepreneur in the White House will draw a new level of attention to national and global businesses. Furthermore, margin and mission are shifting into deeper alignment as many conscious businesses, like renewable energy companies, become profitable. There has never been a clearer opportunity for socially responsible leaders to step into the limelight. If the mission-driven business movement can proceed strategically and open-mindedly, we may stand to gain more traction and attention than ever before. In a sense, the opportunity before us is one we face every day in our own work: we need to scale. But this time, instead of scaling a product or service, we need to scale our values. If 3BL business values were a product, what would it take to get them into every household? Into the hands of every consumer?

The answer may lie in making our movement less partisan and banding together to confront dangers that know no party line: natural disasters, water scarcity, poverty, and disease, for example. We need to take collaboration to a new level. Business can no longer remain a two-party system — conscious and unconscious. To become united, we need to start by acknowledging any progressive initiative within any company, and any leader who is doing the right thing. The time of pettiness and policing is over. We need all business leaders to know that we will not reject them for not being just like us. Rather, we will commend them for any attempts they make to put people and planet on the same line as profit — the bottom one. If the need to judge arises, let us commit to turning the magnifying glass on ourselves before examining others. Am I being inclusive? Am I being tolerant? Am I being compassionate? Am I listening to — and really hearing — what others are saying? Am I focusing on our differences or our similarities?

In the end, Konnect Kloud will always have been founded by a Republican logger. So when Turman drastically reduces carbon emissions while caring deeply for his employees and bringing the intermodal industry into the 21st century, will we congratulate him? Partner with him? Invest in him? Or will we dismiss him, because of the political party he’s historically supported?

I hope we choose the former. I hope we reach out across every proverbial aisle — front, back, and sideways. If we do, we will build the greatest single force for good, business or otherwise, that has ever existed.

Photos by Heather Turman

Risa Blumlein has led and advised nonprofits for 14 years and is delighted to serve the Social Venture Network community as Finance Director. She volunteers with the Nonprofit Overhead Project, the SF Bicycle Coalition, and SOCAP, and serves on the finance committee of the SF Wholesale Produce Market. Risa enjoys writing on Evox and Medium as @TheEmoBiz, a question-asking blogger exploring the juicy and provocative intersection of emotion and business.