Remember the legends of children found in the woods having been “raised by wolves”? Isolated from human contact, they had no manners and didn’t know — or care — about the accepted cultural norms of the society that found them. As a result of their circumstances, their behavior was seen as raw and uncouth by human standards.

In the modern workplace, co-workers arrive at your organization from all types of prior workplaces, some of which could be more analogous to a den of wolves than a conscious company. Recent high-profile cases in the news reveal that some aggressive startup cultures may cultivate questionable ethics and underhanded behaviors in their eagerness for growth, promoting destructive norms that can cause tremendous damage to people, purpose, and profits somewhere down the road—maybe even after those people have found jobs in your organization.

These are likely smart, competent people, but because of where they were “raised,” they may fight with co-workers, create drama, withhold information, or have some emotional maturing to do before they can be a successful leader in a purpose-driven company. This is especially true if they haven’t had a chance to practice more effective ways of working with others. If they’ve been “raised by wolves” so to speak, they’re used to eating food off the ground and fighting for what they need, and they don’t think much about how their actions or behaviors affect other people.

Conscious corporate cultures strive for higher ideals like teamwork, civility, collaboration, and respect for a diverse community, which conflict with hyper-defensive behavior, overt aggression, and sabotaging rather than supporting co-workers. Conscious companies care and invest in culture because they know it permeates everything: decisions, expectations, performance, and more.

Yet even those who purposely escaped from working in a culture where one-upping, yelling, backstabbing, and being critical were the norm may find it hard to adjust to an open, transparent, team-oriented, diverse meritocracy. Building trust, establishing new habits, and gracefully navigating different perspectives takes time.

THE IMPORTANCE OF COWORKER RELATIONSHIPS

Coworker relationships are key in taming the wild wolf habits that might otherwise have a negative effect on your team or culture. One of our clients — let’s call him “Josh” — experienced this situation:

Josh is soft-spoken and conflict averse. He is known for being kind and collaborative in his role as a team leader at a research company. One of his biggest pain points has been holding others accountable when they aren’t delivering what they were assigned or have agreed to do. He’s just not comfortable being confrontational, so he sends reminders and gently coaches team members to get what he needs. As a result, he’s now having trouble with a peer — Tracy — whose work intersects with his.

Tracy came to Josh’s company from one with a very competitive, combative culture. It wasn’t uncommon for her colleagues, even in the same department, to undermine one another to advance their agendas. The employees of Tracy’s former organization fiercely carved out a territory of expertise, chased funding sources, and aggressively defended projects against others who might have tried to claim credit for a discovery or take a slice out of available resources. Although Josh understands this, he feels blindsided by Tracy’s oppositional approach to getting things done.

From the get-go, Tracy has raised her voice at other staff members, interrupted, and seemed to compete for airtime with whoever is in the room. When Josh works alongside her, he feels bullied into solutions that seem better for Tracy than for the company. Josh cares about harmony in the team, and Tracy’s behavior is a violation of the company’s practices around valuing diverse opinions and collaboration. In response, he begins avoiding Tracy, which of course doesn’t solve anything. What he needs is a way to deal with the breach of their culture without creating an enemy.

What could Josh do to bring back harmony? These three stages of change can guide you and your coworkers in deliberately developing more effective behaviors.

USE THE THREE STAGES OF CHANGE TO HELP COWORKERS ADAPT

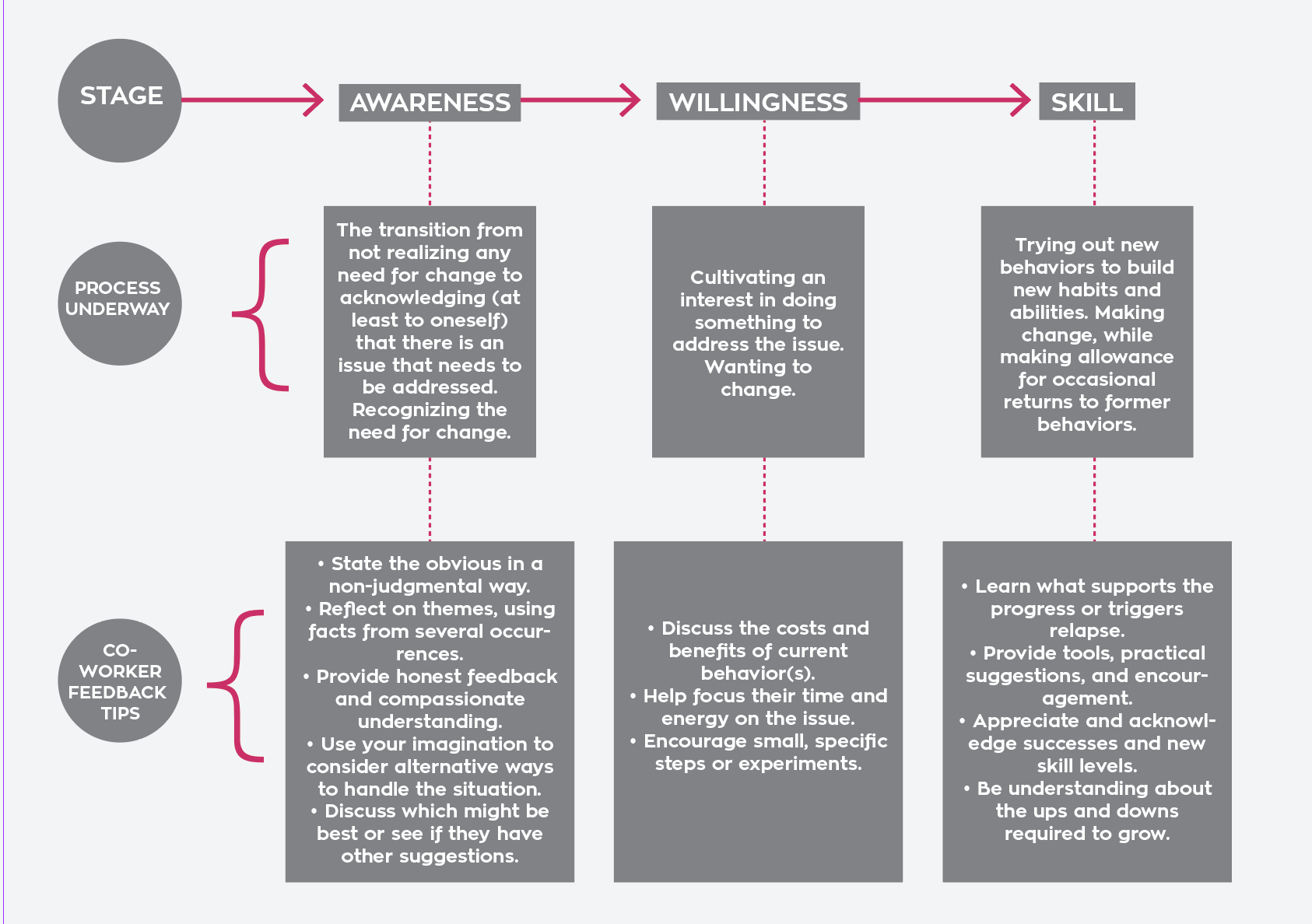

Behavioral change of the type that Tracy will need in order to fit in with a conscious company culture does not happen in one step. When we first try out new ways of thinking and acting, we are clumsy, like a baby learning to walk. Over time, we catch and correct ourselves and learn more effective methods. At each stage of change — awareness, willingness, and skill-building — a person grapples with a different set of issues, and co-workers, including conflict-averse folks like Josh, can help propel these transitions.

1. AWARENESS

Think back to a time when you had a professional growth spurt — a time when you were really learning a lot about your field, profession, or role. How did you first become aware of the areas that needed growth? Perhaps you received feedback from someone pointing out a weakness, or a class inspired you to reach for a higher level. Sometimes we become aware of the need for growth because what worked for us in the past isn’t working any more. Awareness is the first step in the professional growth cycle we all use to become more effective leaders.

Becoming aware of the gap between a desired level of capability and our current ability is the realization that kicks off deliberate growth on the job. Trying to help someone build skills before they are aware of the need to do so can be a waste of time. They just don’t see the relevance and tend to fight to maintain the status quo. Once they become aware, co-workers are more receptive to your efforts to help them — that is, if they are willing.

2. WILLINGNESS

Just because we are aware of a weakness or gap doesn’t mean we are willing to do anything about it. Maybe the issue doesn’t seem that important, or it seems too overwhelming. We may unconsciously resist change by blaming others or making excuses. Sometimes, we are just not in the mood. We are simply not always willing to act on improving every professional area that we recognize needs it. A lack of willingness sounds like this: “I know I should, but .”

When we are willing to improve, we move to exploring alternatives and considering new practices. Perhaps we never want to make the same mistake again, we were backed into a corner, or we inherently want to get better. No matter our motivation for development, willingness is a critical ingredient to growth.

3. SKILL-BUILDING

This is where the action is. We read, discuss, try, study, experiment, ask, try, fail, try something else, get slightly better, and then try again more intelligently. It is an iterative process of developing skill and building new abilities in a specific focus area over time. Along the way, of course, you become aware of another area that needs developing — and then you go through the Awareness / Willingness / Skill cycle again.

When Josh quietly asks Tracy if she is aware that her behavior is inconsistent with their company culture, Tracy explains that intellectual arguments at her last job almost always involved direct criticism. Voices were raised when people argued, but it was valid to challenge one another. It was “no big deal.” It showed people were passionate, she says. Everyone learned to roll with it. Her implication is that Josh should too.

However, successful collaboration in Josh’s company involves more curiosity and stronger teamwork. All voices need to be heard. That means there isn’t room for any one person to dominate meetings or belittle others’ ideas.

Tracy doesn’t believe this is important at first, but after some reflection and observation of how the rest of this team functions, she realizes that she is out of step and begins working on shifting her approach. She talks with Josh before meetings to bounce thoughts and impressions off of him and learns to listen, give more support, and strengthen relationships with team members.

It isn’t a straight line to improvement, and conversations with Tracy are more candid than Josh is really comfortable with, but by building understanding — and learning to laugh at some of their own idiosyncrasies — a stronger sense of cooperation and mutual respect emerges.

It’s unrealistic to expect people to have proper manners when, in effect, they come to us having been “raised by wolves.” Learn to recognize moments of influence with your co-workers and address them with humor and grace. We are all works in progress, with mastery in some areas and arrested development in others. Learning from, and with, co-workers is how we all strengthen professional relationships and synergize a corporate community we can all be proud to work in.