In 1997 year, Diana Chapman was a stay-at-home mom teaching scrapbooking in Ann Arbor, MI — “as mainstream a life as they come,” she says. Then her brother-in-law, the CEO of Monsanto at the time, gave her a gift that would transform her life: $5,000 to use as she pleased. She had always been interested in personal development and human consciousness, so when he made the suggestion that she use the money to learn from the best coaches he knew, psychologists Gay and Katie Hendricks, she jumped on the opportunity.

After studying with the Hendrickses for a decade and taking their work into a business context, Chapman is now one of the world’s foremost experts on conscious leadership. In 2014, she co-authored the influential book “The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership,” and later co-founded the Conscious Leadership Group, a coaching and consulting business. Her mission is to help individuals, teams, and organizations learn how to eliminate drama and suffering from their individual and collective lives.

We spoke with Chapman about what conscious leadership is, how to start practicing it, and the transformation it can bring to workplace cultures of all types. Note: This is an extended version of the interview we featured in our September/October 2017 print issue.

For those who haven’t read it, what is “The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership” about?

Diana Chapman: We say that in any given moment you’re either in a state of trust or you’re in a state of threat. We’re wired to be in a state of threat. That’s a natural state for us. But once we’re handling our survival needs, we can learn to handle longer and longer periods in a state of trust. If you’re in a state of trust, the positive side of that is that you eliminate suffering and drama. The book is all about helping you learn to practice living more from a state of trust — what we call “above the line.”

How do you define conscious leadership?

DC: I say “conscious” is “to be here now,” which most people aren’t. To be here now in a non-triggered, non-reactive state. The moment I’m triggered or reactive I can’t fully be here now — I can’t be “above the line,” and I drop “below the line.”

My definition for “leadership” is anyone who wants to take responsibility for their influence in the world. Anybody and everybody can be a leader if they’re interested in taking responsibility for their influence in the world.

How do you normally get started with the leaders you coach?

DC: One of my favorite things I do with people is say, “If I, too, wanted to have your same problem, what would you tell me to do to create that problem the way you have created yours?” Any person can answer that question no matter how self-aware they are. I’ve never had anybody not be able to tell me.

I was just at a company up in New Hampshire and they said, “We have a bad gossip problem.” So I said to them, “Great. I have another company — they want gossip to be one of their primary challenges in a year. What should they do if they want that to happen?” And everybody laughed and then immediately could start putting together the recipe.

Then they all understood, “Oh yeah, we’re actually all committed to gossip and here’s how we do it.” And then I said, “Great. Now if you want to, you can stop that. All you have to do is the opposite of what you’ve just written down.” I basically help people see how they’re creating the results they say they don’t want. Because another big thing we talk about is this difference between “life is happening to me” versus “life is happening by me.”

How did you actually go from being that stay-at-home mom to doing what you’re doing today?

Diana Chapman: When my brother-in-law gave me that gift, I flew out to California with my husband and we took a five-day course. It was like my entire reality changed after that. A lot of the content that I share with the world — much of it originated from Gay and Katie. And I then devoted the next 10 years to studying with them. I traveled with them all over the country. I taught with them a bit. They gave me their blessing to take this out into the world, and I combined it with other things I had studied, and that’s how I got started.

I met two other women at the Hendricks Institute; one was living in Vermont and one in LA, and all three of us were as deeply devoted as the others to really embodying Gay and Katie’s work. So we said, “God, wouldn’t it be amazing if we could all live close by and really practice this every day?” And within a year we were all living in Santa Cruz, one block from each other.

Probably five out of seven days a week we would gather and practice, for about seven years. We practiced and practiced and practiced. We would physically be together and talk about what was going on in our lives and then we would talk about the content and then we would say what context we were coming from. We were just always looking at our context, moment to moment. So we would say, “Yes, there is a part of me that wants to be right about blah, blah, blah…”

And we would challenge each other’s righteousness, or we would say, “Looks like you have a feeling here,” and “No, I don’t think so.” “Well, check again because we can see some signals.” “Okay you’re right, there’s a feeling here.” Or, “It sounds like you’re in a scarcity of time right now. Just check.” “Yep, that’s true. I believe I don’t have enough time right now.”

We would just keep asking those willingness questions: Where are you, and are you willing to see the opposite of your story? Are you willing to feel your feeling? Are you willing to go have a direct conversation with this person you’re talking to us about? Are you willing to play with this instead of holding this seriously? We were just going through all of those questions over and over again with each other. and we practiced constantly and then when we really felt like we were the embodiment of that work as best we could be, we felt confident to take it out, and we all created our own teaching practices.

How did you know you were ready to teach this? Was there a moment?

DC: I knew I was ready when people started to point to us and say, “Something’s different in you guys and I want what you have. Why is it that you are so enlivening to be around?” And I would say, “Well this is from practicing this stuff.” More people asked me, “What have you got going on? What are these tools that you’re using?” I just kept sharing and sharing until that became what I did all the time.

I was first teaching broadly to the general population. I would go teach weekend conscious relationship courses. I was coaching couples and parents and individuals for maybe a decade, and then finally somebody said, “Hey, I’m going to go facilitate this YPO group. Would you come?” And I did, and I said, “Oh yeah, these are my people.” I loved how fast they were. I loved how curious they were. I loved how knowledgeable they were about the world, and I loved how they longed to be challenged.

I’m known for being quite a challenger, and I felt like my challenger was easily met there. It wasn’t too much for them, whereas maybe in some other populations my challenger felt a little bit too strong. But in that group, they were like, “Please challenge the hell out of me.” And so I was like, “Great. I get to unleash my full self here.”

And so YPO became one of the primary places I worked for years. I worked around the world with YPO, and then ended up having many of them as my clients. So that’s what I do now; help organizations embody the 15 Commitments as their operating system to create a conscious culture.

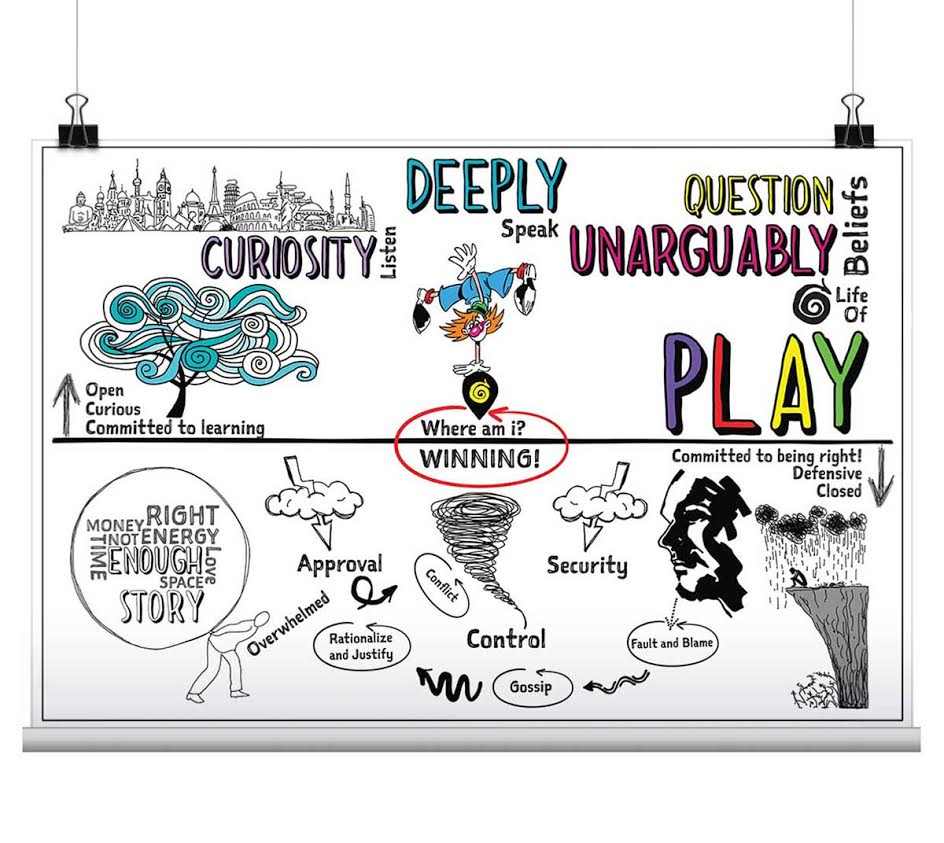

The Conscious Leadership Group’s map of what our minds look like “above the line” or “below the line.” Image by Graeme Franks.

If there were one practice that you could get every CEO in the world to adopt, what would that be?

DC: To recognize and shift wanting to be right. Letting go, really being able to acknowledge that you’re wanting to be right and then questioning that and seeing how the opposite is true.

How you teach letting go of wanting to be right?

DC: One of the ways is directly using Byron Katie’s work. She’s a teacher who basically says all your suffering is happening because you want to be right about the way you see reality. If you simply let go of being right, you would end your suffering.

She has four questions helping people see how the opposite of whatever they believe at the moment is at least as true. For example, “We should grow our numbers by this much this year.” “Great. Let’s say that’s true. Can you see that the opposite is at least as true? That we shouldn’t grow our numbers? Let’s look for real evidence about how that’s true.” We have leaders genuinely go find real evidence.

Or a lot of CEOs think, “I shouldn’t be lazy.” I say “Turn it around. Look for real evidence of how you actually should be lazy. How you could be more effective as a leader if you were lazier?” And many times, at first, they go, “What? That’s crazy.” But if they look, they’ll find, “I don’t rest enough. I’m pretty tired. I think that probably affects my thinking. So yeah, I could see how maybe if I took more naps — what I judge as lazy — I could be more effective.”

We’re always asking people to see the opposite of their thinking so that they can come back to “I am not right,” and from that place they can get curious. It’s just so difficult to really learn and grow as long as you want to be right about the way you see the world.

Once you’re sold that the opposite could be true, what do you do then?

DC: Let’s go back to this lazy example; “I need to drive my team harder. We can’t be lazy.” I’d say, “Look and see how the opposite is true, that you shouldn’t drive your team harder and you should all be more lazy.” I’d get them to a place where they can’t believe their argument on either side, because both sides are true and both sides are not true. Then from that place, I say, “Knowing that you’re not right, listen to your deeper knowing that’s not righteous — what pace do you think would allow your team to be most effective?” So now he’s doing more listening to presence, and from presence, he’s likely going to come up with the pace that will be of most service to maximize productivity and wellbeing.

When you say “listening to presence,” what does that mean?

DC: Presence is this place of listening from the three centers of intelligence: my IQ, my EQ (emotional intelligence), and my BQ (body intelligence). Or, to go back to the definition of “conscious,” to be here and now and in a non-triggered, non-reactive state. And by the way, I can’t be non-triggered and non-reactive if I want to be right about the way the world ought to be.

So the idea is: I’m present, I’m non-triggered, I’m having full access to my IQ, EQ, and BQ, and from there I listen to my own deep knowing of what would most serve and support me and my team.

How does my “deep knowing” know what my team needs? Shouldn’t I go ask them?

DC: Yeah sure, you could go ask them, and that might be valuable. But even when you ask them, they may all be a bunch of workaholic adrenaline junkies and they may all say, “What works for us is let’s drive this baby so we can go make a bunch of money.” You may listen and say, “I don’t know that that’s actually in their best interest.”

For me at least, my heart, my mind, and my body give me feedback that helps me know what might most support everybody. I can’t know whether I’m right or not, because there is no right. All I can do is take a stand in one direction or another and learn from my results. But my experience is that when I’m really present and I have access to those three centers of intelligence, almost all of my decisions seem to serve and support me and others.

How can teams instill the commitments you talk about in your book across their cultures?

DC: I would recommend doing a book club where you and your team read one chapter every month, and you have a lunch where everybody sits together and you spend at least a good hour talking about, “What did we learn from a chapter? What are some of the examples of how this is applying to us and our lives?”

And then create some practices. We recommend that everybody has an individual practice that helps them practice each commitment for the month. One of the things we use is an app called Mind Jogger . It will pop up on your phone with a question related to the commitment we’re working on; I usually have mine trained to seven times randomly per day. So it would say, “Diana, in this now moment, are you above the line or below the line?” Whenever that pops up, I check, “Where am I?” I don’t have to do anything other than just be aware of where I am. If everybody has that on their phone and everybody’s practicing individually, you’ll start to notice the culture shift.

Then anytime there’s a meeting, start with “Where are we?” Everybody does what we call a line check; “I’m above the line” or “I’m below the line.” Again, we don’t have to do anything more with that except just be aware of what’s going on. That said, let’s imagine we’ve just run into an emergency and we all recognize that we’re below the line. We might want to spend a little time seeing if we can create a shift for ourselves so that we don’t try to solve the emergency from a state of threat, because we’re going to be far less effective.

Is there such a thing as a toxic person within a culture, or does everyone have the capacity to develop and transform and be a working member of a team?

DC: My experience is that almost every team has some level of toxicity in it, whether one member or two or three or more, who are deeply committed to being victims. They’re living in a victimhood state. They are “at the effect of” whatever it is: leadership, the crappy work, the work hours, compensation, whatever. And they are angry and they are disengaged, and in many cases are trying to disengage others. Any of those people can change into a productive member.

Everybody has the capacity, but not everybody has the willingness. What leadership can do is offer up ideas. You say, “This is our operating system. Is this a system you’d be willing to practice and grow into, yes or no?” If the answer is no — which is perfectly acceptable, it’s not a moral judgment — then we know those people are committed to being victims and they’re not going to shift. Then I recommend cutting them out. But if the answer is “We’re willing to learn,” then great. We can help you learn, help you question your thinking, feel your feelings, learn how to lead direct conversations, and start to be in a state of appreciation. We can help you learn to play with whatever challenge might have been so serious.

I have seen so many toxic people turn around. I have great hope for people. It just requires their willingness.

I always say “wanting to change” and “willing to change” are two very different things. Some people will say, “Yeah, I want to change,” but they’re actually not willing. And therefore the drama doesn’t end.

What do you see as the role of business in solving social problems and creating a better world? How do conscious leadership and the practices you teach factor into that?

DC: One of our 15 commitments is a commitment to a win for all. What I’d say is, “Hey, whatever you’re doing in business, is that a win for you? Is it a win for your clients? Is it a win for the environment? Is it a win for everybody?” My thought is that if we just all ask that last question, “is it a win for everybody?” then we don’t even have to ask the question “Are we making a social contribution?” because it’s just inherent.

I want to challenge a lot of the people who are in some of these “green company” movements, or purpose-driven or B Corps or whatever, who are saying, “We’re here to make the world a better place.” When I look at the whole way they’re doing business, I say, “There are still many places where you’re not creating a win for all.” Is there a win for our employees’ children with the pace at which we work our employees? Would their children say it’s a win for how much access they have to their parents as they’re growing up? I want everybody to keep looking at, is everybody being served with what we’re doing, or is somebody having to pay the price?

There’s no such thing as a free lunch. Doesn’t somebody have to pay for something eventually?

DC: That’s how everybody thinks. From a conscious state, we go, “Oh, let’s see. What would it look like to create a win for you and a win for me?” And it doesn’t mean that you just get a free lunch, because if you got a free lunch it wouldn’t be a win for us over here. So what is it that you need, what is it that I need, and then how do we help create both of us getting the need met?

And that’s not a compromise. Because a compromise is a lose–lose. It’s really looking for, how do we create it so that both of us get the win? Which means we have to go out into the unknown and get deeply curious, because it’s likely not going to be really obvious. If it were, we’d all be creating wins more often.

For example, let’s keep it simple, let’s say we’re friends and we want to go out to dinner tonight and you say, “Oh, my God. I am so craving Mexican.” And I say, “Actually going to Mexican isn’t a win for me. I’ve eaten Mexican three nights in a row. I can’t do it again. I really would like to do Italian.” And you say, “I don’t want to eat a bunch of pasta and there are very limited options there.” Now what do we do? From a conscious place of deep curiosity we go, “What would be a way we could create a win–win?”

Maybe there is another possibility, like Asian fusion. Or maybe you go, “I really wanted to have Mexican.” So we go, “Okay, well here’s some options. What if we go either eat at my house or go out to the beach for a picnic, and you grab your Mexican, I’ll grab my Italian, and we go have a meal that way. Or if we have the time, I’m happy to sit with you and have some Mexican. I’ll have a margarita and then we’ll go grab some Italian.” There are all the different ways that we both get to win. The idea is that we keep staying in the game until we find a win for all. And my experience is that we always can find something.

I was with a 20-person group the other day and we were talking about where we were going for dinner. I said, “I want to hear everybody’s preferences.” We had almost 20 different perspectives, but we came up with a result that was a win for all. It takes so much creativity, innovation, thinking. You have to open up to not having a scarcity of time, not having a scarcity of money or a scarcity of resources, while still acknowledging that we have finite time, finite resources.

What’s the most important thing in your life right now?

DC: Well there are two things. I’m deeply into the question right now of, moment to moment, how do I support my maximization of my life force? That’s something that comes up on my Mind Jogger randomly: “Diana, in this now moment, are you maximizing your life force?” Being devoted to my life force is one of my big purposes in life now.

Then I’m redesigning my entire calling here to see how can I be most impactful. I’m letting go of many of my current clients and asking, “What is the best use of me — to get this work out to the most people and have the most positive change?” I’m still in a bit of a query about that right now. How do we get this book into more hands? How do we get more people practicing? How do we highlight organizations that are using this and inspire others to? How do I get myself in front of more influential people? That’s the big thing I’m up to right now.

When you say maximizing your life force, what does that look like in practice and what are some of the practices you’re experimenting with to do that?

DC: We believe that all of us have a zone of genius. It’s that thing that when you do it, time and space go away. It’s not something that you necessarily developed over time. It was there from the very beginning; probably your parents would have said, “We saw those skills right when they were little.”

And sure, of course you can create more mastery, but they are these innate things that you do and when you do them, time and space go away. It is a maximization. You actually feel more energized doing it. A lot of people do what I call the “zone of excellence,” these things that they’re good at but that don’t ignite the life force — “It’s okay because I get paid well,” or “People like that I do it.” That’s one place where I’m putting a lot of attention: what really is my zone of genius and how do I spend the majority of my time in that?

Then I really like the power of full engagement from The Energy Project; this idea that we have these four different energy bodies: physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual. And so I’m looking at, how do I maximize my physical? Deep listening: what really is the best time to go to bed and to wake up? Where do I feel the most maximized? What does my diet look like, specifically to me — forget what everybody else says? If I listen to my own results, what maximizes my energy based on what I eat? And how about napping, and how does that support it? And exercise, what serves my body best? Who do I hang out with? When I’m around them, my energy rises versus falls — and not spending time with people out of obligation. If my energy drops, that’s a waste of my energy. Who is available to receive what I have to offer and wants it, versus sitting in front of people who aren’t that willing and available, which is not enlivening for me?

Those are just a few things that I’m putting my attention on. The other thing is the environment that I’m in. Is everything I’m around bringing energy? This morning I was holding onto books on my bookshelf one at a time going, is this maximization of my energy to have this book on my bookshelf? And I literally do that with every one of my physical belongings. Is it still in current time? Does it still give me that whole-body “yes to owning it”? Is there anything that needs to be fixed? Is it in the right place? Living in a state of completion, I call it. It’s maximization of my energy.

Is there anything we didn’t ask you about that you want to make sure to get to talk about or that you think we should know?

DC: Yeah. I want to be provocative for a minute. I want to challenge the mindfulness movement and I want to say that I see a lot of emphasis right now on meditation, sitting on my cushion. I say that is fantastic. I am so thrilled. I think it’s incredibly important. In fact, I’d argue that every organization ought to have meditation be part of every job description.

However, the mindfulness movement has so many limitations because for most people, when they get off that cushion and they fall immediately into threat and they don’t have good tools for how to deal with that when they’re off the mat.

People need to learn practical skills when they’re in relationship, when they’re off the cushion. There’s so much more that needs to be shared, so many more tools that need to be embodied to really be successful.

I also think there is a limitation in the conscious leadership movement in that people can get too focused on having a purpose. I know lots of very purposeful companies who have massively fucked-up cultures where people are really not happy with each other. So I’d say I don’t care whether you have a purposeful business if you don’t have conscious relationships built. I definitely want to challenge the whole conscious leadership movement. I would like to see more emphasis on the practical skills of being able to relate from a place of trust versus fear, or from recognizing that I’m the creator of my reality versus a victim to my reality.

The other thing I would just say is that I want more challenger energy. My stories about many people : they’re all afraid to be “mean.” That’s a common theme I keep seeing, no one wants to have the difficult conversations. Everybody’s trying to control so much that we’re keeping ourselves stuck. We don’t have enough challenge coming out in the culture right now, in our whole collective culture, challenge to face what’s not working. I want to feel more challenge or energy in general in our world.

One of the things I’m really excited about is helping train people how to be comfortable in the discomfort. I think that if we don’t consciously choose to get more uncomfortable, we’re going to unconsciously choose it by creating a really unsustainable world that’s going to force us to get really uncomfortable.

What’s giving you hope?

DC: So many things. One is that when I first started doing this work with businesses about 10 years ago, there were differences between the West Coast and the rest of the country, palpable differences. I’ve traveled and worked with people from everywhere for years now, and I truly believe that there is a collective interest and willingness to shift and that the distinctions are not so drastic anymore between the West Coast and the rest of the world.

What else gives me hope is that those who are practicing acknowledge that life is becoming a much more satisfying experience and that their suffering is reducing, they are more engaged with the people they live and work with, they have more energy, and they’re more creative. That gives me so much hope that it’s possible, because when we first started out we didn’t know if this was really going to be something we could easily pass on to others. We’re learning that we can.

Also, my co-founder Jim Dethmer and I weren’t sure if we could train other people to really deliver , and we have found that we can, so we’re mentoring more and more coaches to help get the word out.

The Millennials give me a lot of hope. What I believe is that they are shifting their relationship to greed. They’re greedy with their addiction to technology, but they’re not greedy with money in the same way. I’m very hopeful about that.