At age 34, Justin Rosenstein has already had more cultural impact than most of us can hope for in a lifetime. In his first job out of Stanford as a product manager at Google, he invented and wrote the original prototype for Gchat in a single overnight coding push. After getting recruited to Facebook by its co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, Rosenstein and a few buddies invented the Like button. Those two inventions alone subtly affect the lives of perhaps a billion people every day. But if all goes his way, his previous accomplishments will be minor compared to the impact his current job will have on humanity’s wellbeing. His end goal: universal love. His tool of choice: enterprise software.

Asana co-founder and head of product Justin Rosenstein

Follow his logic from its source, and it makes a certain kind of sense. At both Facebook and Google, despite being so obviously productive, Rosenstein was still frustrated by how much time he spent doing work about work — endless meetings and status updates. In response, he created an internal software tool to help facilitate collaboration. By the time he left Google in 2006, about 1,000 people were using the barebones product he’d hacked up in a few weekends. At Facebook, he got Moskovitz involved in a similar internal project, and they soon watched the number of status meetings plummet and productivity soar. The tool was so effective that Moskovitz stepped out of his role as VP of engineering to focus on the software full-time.

Eventually, Rosenstein and Moskovitz decided to share with the world what they were creating: a tool that helps teams simply track, manage, and complete their work with clarity. Their grand plan was to create a product that would improve the results of any team trying to accomplish lofty goals across any field, from healthcare to clean energy to social justice and beyond. “If you could get the people in organizations to coordinate as effortlessly and effectively as the limbs of my body,” explains Rosenstein, “the power of those emergent selves would be mind-blowing — capable of things I don’t even think we can conceive of today. And then if you could get all of humanity to collaborate toward commons ends …” He trails off at the enormity of it.

And so Asana was born.

The pair launched their startup in 2008, naming it after the Sanskrit word for postures from yoga, a practice important to both cofounders. The name also captures the sense of flow and focus that they hoped their software (also called Asana) would help workers achieve. In an unusual enterprise sales strategy, they decided to make the product free, with premium features and support available to paying customers. They attracted $1.2 million in funding from 14 angel investors, including from big names like Peter Thiel, Mitch Kapor, and Marc Andreessen.

Asana At A Glance

Location: San Francisco, CA

Founded: 2008

Employees: 297

Structure: Private for-profit

Impact: 25,000+ paying customers

Major funders: Andreessen Horowitz, Benchmark Capital, Founders Fund, Peter Thiel; latest round was Series C led Sam Altman.

Mission statement: “To help humanity thrive by enabling all teams to work together effortlessly”

In 2011, they launched their browser-based and mobile apps. As the team expanded, they settled in a historic former brewery in San Francisco’s Mission District and watched their market share grow, along with their funding — in total, they’ve raised more than $88 million in three rounds. Though the company doesn’t reveal revenue figures, as of late 2017 it boasts 25,000+ paying clients (up from 20,000 earlier in the year), including big names like Zappos, HBO, AB-InBev, and Airbnb. According to a listing on the Great Place to Work website, the company plans to hire 94 positions in the next year to add to its team of almost 300.

Yet the success of the software and the company’s fast growth are not why I’m dedicating two and a half days to interviewing employees and sitting in on meetings at the company’s offices. I’m here trying capture what makes Asana tick because of the first-class workplace culture Rosenstein and Moskovitz have created. The company’s Glassdoor rating is a 4.9 out of 5. According to Great Place to Work, 99 percent of its employees say their workplace is great, and Asana recently was among the top 10 tech companies on Fortune’s Best Workplaces for Women 2017 list. Fast Company recently called it “the best company culture in tech.”

Dustin Moskovitz, a Facebook co-founder, is CEO and co-founder of Asana

This human-level success is no accident. The founders articulated the basic principles for the culture they wanted to create during the company’s first week, when it was just the two of them, and early employees report that the atmosphere has felt deliberate from the start. Both Rosenstein and Moskovitz often talk about how they treat their culture as a product, just like their software — one that deserves intention, attention, design, and upgrading just as much as any app feature they might ship to customers. Experimenting with how corporate structures, mindsets, and rituals can facilitate teamwork is just as important to their mission to “help humanity thrive by enabling all teams to work together effortlessly” as improving the usability and success of their app. While they don’t explicitly sell or export elements of their culture (yet), they do devote significant staff time and resources to sharing their findings on a popular blog and a web publication called Wavelength. Some of the app’s design also represents their philosophy about effective teamwork — the fact that tasks can only be assigned to one person is an extension of the company’s position on the importance of clarity of responsibility, for example.

Meanwhile, as Rosenstein puts it, “We’re doing extremely well as a business, and it’s because of, not in spite of, all the emphasis we’ve put on mindfully building a great culture. It allows us to move more quickly because we’re not wasting time on infighting and drama. We have the processes we need to learn more quickly, so we make fewer mistakes over time and get more successes. And it’s the thing that allows us to retain and attract some of the top talent in the world, because that’s an environment that great people want to work in.”

So what really makes Asana’s culture special? And are there lessons here for other visionary organizations? That’s what I’ve come here to discover. And the answers seem to start at the source.

ASANA’S MINDFUL FOUNDERS

There’s a lot about Rosenstein that makes him an unusual, or at least distinctive, C-suite leader. He’s brilliant, of course — he graduated from Stanford with a math major in two and half years, which he humble-brags might be the fastest ever — but I don’t mean that. I mean his way of being. How he often walks around the office without shoes. The way he usually sits in meetings — legs drawn in close, pretzeled into his seat. His unabashed obsession with cats (he and his team of assistants call their corner of the office “the Meownge,” short for Meow Lounge, and it’s decorated accordingly). His vegan diet. His t-shirt-and-jeans wardrobe. The fact that he lives with 14 roommates in a cooperative he founded in a big Victorian house in the Mission District, and the fact that it’s named Agape, after the Greek word for unconditional love. His deep commitment to Buddhist-inspired personal development practices; he spends several weeks a year on silent meditation retreats. The list goes on, but these are mere effects of the core traits that make JR (as his team and friends call him) an unusual leader. The first-principle qualities, which make up the ether from which the constellation of his quirks emerge, are that he’s unusually authentic, humble, and self-aware. And in embodying those qualities in himself, and by choosing a co-founder who is equally dedicated to them, he’s manifested (his word) a corporate reality that embodies them too.

The difference really clicked for me as we sat discussing what his role at the company has become lately. It was the start of Roadmap Week, a ritual Asana has been doing since its early days, in which normal operations stop so that the teams can take stock of what they’ve accomplished in the latest “episode” (a six-month period between Roadmap Weeks) and look to where they want to go in the next one. Rosenstein talks about it as a form of corporate mindfulness, like organizational meditation — a time to pause and grow awareness of what is. He wasn’t leading any meetings that week, but he was sitting in on a ton of them so that he could glean a sense of the big-picture challenges facing the company’s various arms, and perhaps see solutions across departments that others might not.

“Often my role is just that I can be more daring,” he explained. “When you join a company, it’s so easy to just take things for granted — that things will always be the way they are; whereas a lot of the decisions that people think are set in stone are decisions I personally made, and therefore it’s very easy for me to question them.

“I have a very sophisticated operating model about how the world works, how companies should work, what product we’re building, what features it should have, different cultural practices we should adopt. But I don’t believe any of it. And so, if, at any moment, the argument comes along that would demonstrate that part of my operating model is wrong, I just drop it. Having that kind of total intellectual humility makes it a lot easier to work with people. It’s hard to get into fights.”

Moskovitz, the company’s co-founder who has been CEO since almost the start (he and Rosenstein switched at one point early on), also professed a similar position. “Strong opinions weakly held,” he called it. “I’m always trying to question, ‘What do I think I’m right about? And how might the opposite of that story be true?’ It’s just a common way we have of looking at things.”

“Strong opinions weakly held.”

At one point I asked Rosenstein if he’d always been this way, or if it had taken work to get so light with his beliefs.

“It’s an ongoing practice,” he said.

“What do you do if you notice you’re clinging?”

“Mindfulness: Notice the clinging. Equanimity: be ok with the clinging. Observe it as a phenomenon of, ‘I am a human, I cling to things. That is a thing that humans do. That’s ok too.’ Then as much as possible, just trying to relax. Breathe.” Then we both did.

EMPOWERMENT

About a month after Roadmap Week, the regular Friday Product Forum is starting in a conference room decorated like a cozy den or therapist’s office, all warm grays and soft curves. As usual, Rosenstein embodies the lithe self-containment of a cat, his legs curled under him as he sits in a corner of the couch, dressed in a black t-shirt, black jeans, and black socks. Rosenstein’s official title is head of product, and the goal of today’s gathering is to offer feedback and guidance to various product development teams about the design of the software. But Rosenstein is not in charge of the agenda, nor of the timekeeping. Neither is the number two executive in the room, head of project management Jackie Bavaro.

This regular meeting, which was originally known as Product Review, has recently been renamed to make it clearer, especially to new employees, that this isn’t an arena in which Very Important People in Power are going to rule from on high about the work of subordinates. Instead, it’s an opportunity for informed and experienced coaches to help teams make the best decisions possible about how to proceed.

The first group to enter has been working on a new version of the Asana iPad app. The project lead projects a version of the app on a large screen in the corner of the room and hands an iPad to Rosenstein, who immediately starts exploring.

Rosenstein begins by just pointing out what he’s noticing. “As always, take these things for what you will,” he says. “I’ll note if I see anything that definitely has to be addressed; otherwise take it as input.” As he investigates the functionality of the app, he frames his notes from the seat of his own experience, or as clarifying questions: “I would expect the ‘My Tasks’ bar to go all the way over to the right.” “This is pretty surprising to me …” “When I see this with a beginner’s mind …” “I hear you saying …”

After about 15 minutes of back and forth, he concludes: “I think it’s safe to say this is a strict improvement. Approved!” And it’s time for a new team to move in.

Areas of Responsibility (AORS)

It’s worth noting that as hands-off and non-directive as Rosenstein’s feedback is, this moment of granting approval — as the gatekeeper and final decider of the fate of someone else’s work — is a glaring exception to the bulk of operations within the company, one that only occurs about what gets shipped live in the app. In general, Asana structures its work around “areas of responsibility,” or AORs. The idea is that every possible task required — from logo design to compensation to customer support for Europe, and from app stability to making the sauces for the three daily meals the culinary team serves in the cafeteria — is documented as a clear area of responsibility with one specific person who is its DRI: directly responsible individual. The trick is that unlike in most organizations, the DRI, otherwise known as the AOR holder, is genuinely responsible and empowered to make the final decisions regarding their AORs. Managers are there to coach and support AOR holders, not to approve, reject, or direct their decisions. Rosenstein calls this model “a distributed dictatorship.”

Bavaro, for example, is the AOR holder for the company’s annual software work plan, deciding what features they’re going to add and what improvements they’re going to focus on. While she has a duty to make sure she understands the requests, desires, and points of view of all relevant parties — including Rosenstein, who is her direct manager, and Moskovitz, the CEO — it’s truly Bavaro’s responsibility to make the decision: “What are we going to build this year?” In the lead-up to that decision, she collects feedback, not with the goal of building consensus, but with the goal of mutual deep understanding.

“It’s much more important to feel heard than to get your way,” Rosenstein explains. “If I feel like someone didn’t understand my perspective and they decide differently than I would, that’s really frustrating. If I feel like they understood and they just had a different intuition or made a different judgement call, that’s a lot easier.”

“It’s much more important to feel heard than to get your way.”

Anna Binder, head of people operations, explains AORs with a story about a meeting she attended early in her time at the company. “It was a pretty large meeting about strategic planning,” she says. “There were a lot of different opinions in the room. Moskovitz looked around and said, ‘Listen guys. I have such strong opinions about what the outcome here should be, I’m worried that once I start talking, I’m just going to spend the whole time trying to convince everyone of my point of view, and that because I’m the CEO, we’re going to go with my way because it’s my way. But that’s not what I want, because I’m not the AOR holder. So, if you would allow me to state my opinion, I’m then going to leave the room. Leaving the room is not a statement of “I don’t believe in you” or “I don’t care;” I just don’t want to disrupt the process.’

“I’ve worked for a lot of different CEOs before,” says Binder, who has held similar roles at several other tech companies. “I’ve worked for CEOs who really are the smartest person in the room, but could never have taken such a long view.” Witnessing that humility and self-awareness was “an amazing experience,” she says, but what happened next was “even more amazing.” Before Moskovitz left, several people, including the AOR holder, asked him some clarifying questions. Once he was gone, the conversation turned to, “I think we understand what his priorities are. Do we agree with those priorities?” In the end, the group came up with a better solution that completely solved his problem. “I hadn’t been in an environment like that before,” Binder says. “It was incredible.”

The Origin of AORs

AORs started early in Asana’s history, well before there was even a product to launch. In part, they stem from that value of deep intellectual humility that both Rosenstein and Moskowitz share. “I don’t particularly want to make decisions,” Rosenstein says. “I think a lot of leaders have the personality trait of wanting to make the call. I just want the right call to be made. And given that we’ve gone to the trouble of hiring talented, smart people with good judgement, of course you want to distribute the responsibility to the person who can make the best decisions.”

“It almost feels like a failure if I’m doing something directly or making a decision directly,” adds Moskowitz.

Another reason for AORs goes back to a difficult experience Rosenstein had while at Google. He’d been leading development of Google Drive, and brought what he thought was a viable product to Larry Page, the company’s founder and CEO, who decided it couldn’t launch until it integrated with a bunch of other Google apps. Rosenstein explained the major political obstacles to getting that done, and thought that launching Drive right away and integrating later would make more sense. Page overruled him.

When he built his own company, Rosenstein vowed to do his best to eliminate such situations, in which one person is the subject-matter expert and a different person is the decision-maker. “When I’m in conversation with designers and we disagree,” he says, “unless I really disagree, we try to get to what at Amazon they call ‘disagree and commit.’ ‘I disagree with you. But you’re thinking about this 100 times more than I’m thinking about it. You’ve heard my advice; if that’s what you want to do, I’ll stand behind you. If it turns out you learn something else , then you learn.’”

MENTORING

One way Asana cultivates a low-drama workplace is by encouraging employees to bring their full selves to work.

Bella Kazwell kept telling herself she wasn’t ready to manage an intern. Though she’d graduated with a degree in computer science from Carnegie Mellon, sailed through internships with Nortel and IBM, and spent six years as an engineer at Google right out of college, she arrived at Asana in 2011, as the company’s 19th employee, convinced she wasn’t good enough to mentor anyone. She held on to that belief even as she thrived at Asana and, as the first one to take advantage of it, helped the company create its parental leave policy. When she returned, her manager helped her craft a flexible schedule, and they also decided that enough was enough with this “not ready for an intern” talk. She took one on.

It turned out that Kazwell loved the coaching involved, and she soon asked to move into more leadership roles. Today, she’s the web engineering lead, and manages a team of 16 people in that department.

Kazwell is both a beneficiary of the company’s focus on mentoring and is in a role explicitly providing it, so she considers it a lot. “When we think of staffing,” she says, “we think of how we’re enabling this person to grow. How can we give this person a challenge, and how can we support them in this challenge?”

Managers as Coaches

Most fundamentally, the culture of mentoring stems from the way Rosenstein and Moskovitz look at roles within the organization. “The primary function of managers at Asana is to support the individual contributors to manifest their potential,” Rosenstein says. “We talk about the manager as coach. As a manager, when someone brings you a problem, there’s a strong instinct to want to solve it for them. And sometimes that’s the appropriate response. But it’s astounding how often that does a disservice to your organization. Often all I need to do is patiently hold space. I ask, ‘What do you think you should do?’ By the end of 10 minutes, they’re often like, ‘Oh … I guess I should do this,’ and I’m like ‘Yeah, that seems reasonable,’ and they can go forward. But now they’ve developed a skill, rather than just me handing them an answer.”

In practice, this coaching work emerges mostly through regular one-on-ones between reports and managers. “At a lot of companies, those meetings get devoted to talking about what you’re working on — status, deadlines,” Rosenstein explains. “Because that’s all tracked in the Asana app, it opens the one-on-one to a broader conversation. What are you feeling? What’s holding you back from being able to blossom and do your best work? What would you like to learn and develop skills around? What are your long-term career aspirations? What are your long-term human aspirations?”

The commitment to mentorship and helping employees grow starts on an employee’s first day when they’re assigned an on-boarding buddy who is expected to spend significant time helping them get up to speed. Meanwhile, the company also offers peer mentoring, both informal and formal; executive coaching to all employees; communication coaches; and more — services rarely available to every employee in an organization.

CLARITY

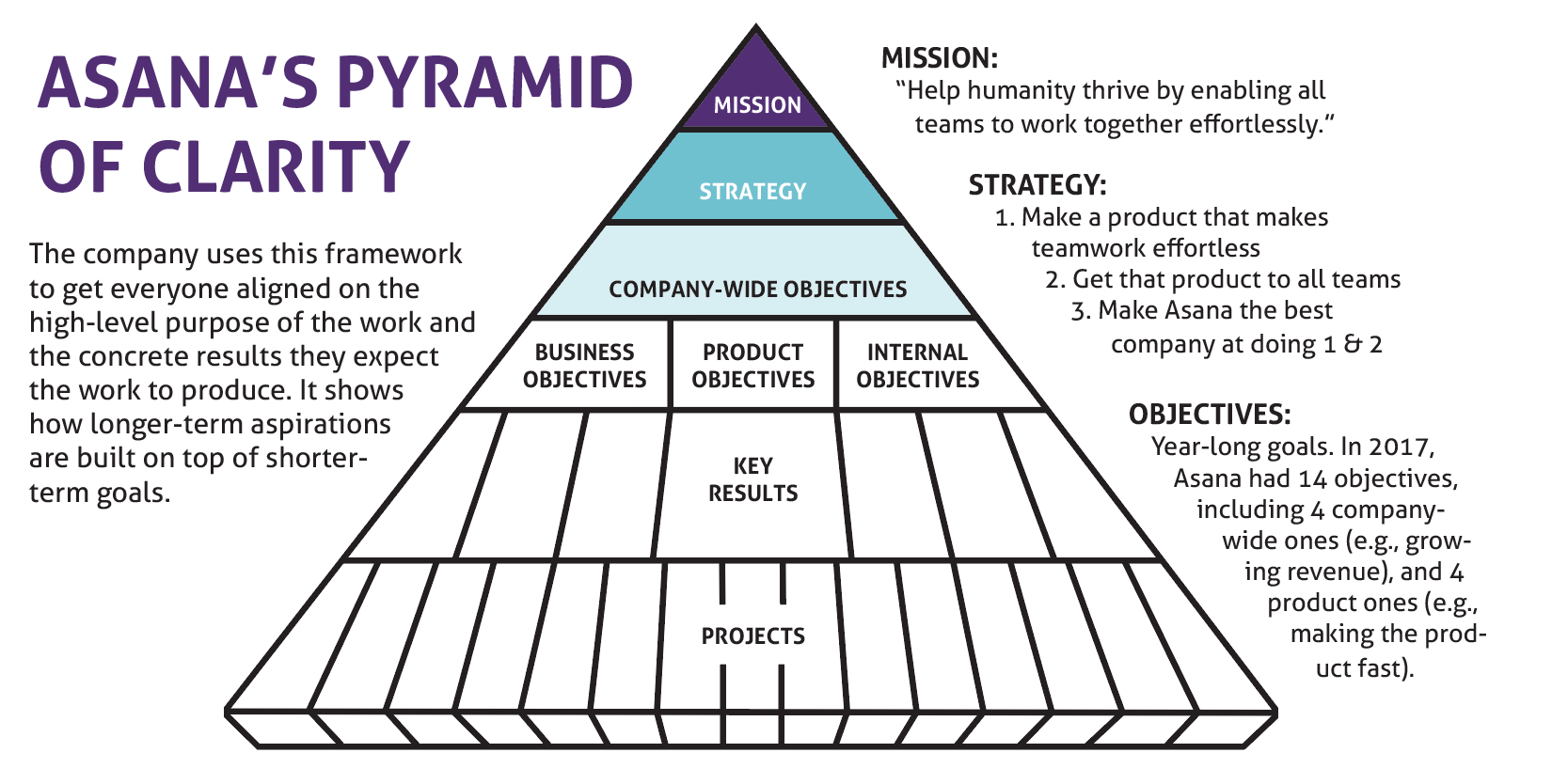

“Something that feels really special here is that there’s been this huge investment over time in connecting the dots from the work one person is doing to the mission,” explains Bavaro, the head of product management. Employees use their internalized understanding of a framework Moskovitz calls “The Pyramid of Clarity” (see below) to examine the consequences of decisions from a high-level point of view.

“Any time you’re working on a task at Asana, you can know that this task is part of this project, which is in service of this key result, which is in service of this objective, which is part of this strategy sub-bullet, which is part of this strategy main bullet, which goes up to the mission. At a Roadmap Week meeting I was just at, a team was saying ‘We’re trying to make a decision about what we work on.’ We were able to have the conversation at that high level, rather at the level of ‘Do we build this feature or that one?’ The question became, ‘Between Objective 10 and Objective 12, which do we think is most going to help us with our strategy?’”

“Any time you’re working on a task at Asana, you can know that this task is part of this project, which is in service of this key result, which is in service of this objective, which is part of this strategy sub-bullet, which is part of this strategy main bullet, which goes up to the mission. At a Roadmap Week meeting I was just at, a team was saying ‘We’re trying to make a decision about what we work on.’ We were able to have the conversation at that high level, rather at the level of ‘Do we build this feature or that one?’ The question became, ‘Between Objective 10 and Objective 12, which do we think is most going to help us with our strategy?’”

Starting with Mission

The first key to achieving this level of clarity, not just among executives but among a fast-growing web of empowered employees, is the mission. As research on mission-driven business has shown, having a purpose beyond profit is a strong tool for driving better performance on a constellation of business metrics. And that research also makes it clear that said mission must be alive and active in all decisions all employees make, not just a nice platitude on the website.

At Asana, Rosenstein is a secret weapon in helping that mission come alive. It helps that Asana’s mission fuels his personal priorities, but it’s not just that he thinks the work he’s doing helping teams be more effective has the power to change the world in a big way — he also communicates it often and effectively. “I think he can see 10 years in the future as clearly as I can envision tomorrow,” says Bavaro. One of his AORs is “toastmaster.”

Yet Asana doesn’t just depend on a visionary and articulate leader to keep its teams aiming toward the same goal; the company also invests in clarity through some day-to-day norms in the culture. Roadmap Week (RMW) itself is perhaps the best example — a twice-yearly chance to reflect on what went well in the last episode since the previous RMW, and to zoom out to make big-picture decisions about the next episode. The company also holds all-hands show-and-tells every few weeks where individual contributors share what they’ve been working on. And it uses its own app, with its task assignment and communication tools, to focus on turning ideas into action items with a clear owner and timeline and keeping everyone easily up-to-date on progress.

FEEDBACK AND CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

It’s Tuesday morning, the start of the second day of Roadmap Week, and a group of about 15 Asana employees is gathered around a large glass table to discuss … Roadmap Week. Well, not just RMW, special weeks in general. Besides the biannual RMWs, the company also has several other special times built into the annual schedule: Grease Week, for cleaning up internal systems and processes; Polish Week, for making similar improvements to customer-facing elements of the business; and a few hackathons scattered here and there for fun, fast prototyping of new ideas. The purpose of today’s meeting is to make sure the special weeks are still working well, that the company still wants them, and to improve them if possible.

As usual, the relevant AOR holder, in this case Matt Bramlage from the developer relations team, leads the meeting, and has come prepared with a Google Docs agenda, questions for the group, and goals for the conversation. Those around the table represent a variety of departments and the remote offices. The conversation centers around how not everyone really understands the nuances of the various weeks, and how challenging it can be for non-product teams, like customer success or marketing, to really participate in them. Someone suggests that maybe Grease and Polish weeks should just be for product teams.

“I think we’re getting the wrong signal from it being challenging,” says a woman on the customer operations team. “Because it’s harder to include everyone, it’s information to me that it’s even more important.”

“If widespread participation is important to us — maybe it isn’t — but if it is, we need people to realize it is. We need to incentivize it,” points out a purple-haired woman on the marketing team. “Maybe a t-shirt? A sticker or laptop badge?”

“The hypothesis is that there’s not enough incentive to participate, but I don’t know if we’re getting at exactly why it’s hard to participate. I want to make sure we feel like the solution is matching the problem here,” a product manager reminds the team.

“Can I make a proposal for some action items?” asks a representative from people operations as the meeting draws to a close. In the end, the group decides that all the weeks do still have value for now. They’ll create a liaison within each department to spearhead participation in each special week, circulate templates for week launches with longer lead times to help communicate the goals and get people clear on opportunities, and improve communication about the weeks in general.

This meeting is a relatively low-stakes but real example of another set of values that, in the end, are probably the most important for explaining Asana’s success and the ones most adoptable by any company: candor and continuous improvement.

“A lot of what makes the culture as good as it is is that we notice bugs,” says Rosenstein. “There’s bugs everywhere, there’s problems everywhere; as the company grows, there’s always challenges. The key thing is just to keep noticing those challenges and trying to improve them. It’s permanently a work in progress.”

“A lot of what makes the culture as good as it is is that we notice bugs.”

5 Whys

Another mechanism the company commonly uses, called “5 Whys,” is one it adopted from Toyota. Teams exercise it any time something goes wrong. “The process is, you say, ‘This thing went wrong: we pushed a bug to production,’” explains Kazwell, a 5 Whys veteran who now helps facilitate many of these reflections. “‘Why?’ ‘Because we didn’t test it.’ ‘Why?’ And it keeps going. It’s not about blame, it’s about process. Things go wrong, people make mistakes. You want to put in processes so people won’t make mistakes, or at least protect people from their mistakes. It’s important to have the people who were involved in the room, because otherwise you end up hypothesizing and come out of the meeting with no decisions. And it’s important to come out with action items. It’s tempting to just make this a venting meeting, but the goal of this meeting is to figure out what went wrong and how we’re going to fix it.”

Feedback

As part of the emphasis on always improving, the company also has a deep commitment to ongoing feedback. “We have lots of forums for it and we’re always looking for the best ways to help people give and receive that feedback in a non-defensive manner,” says Bavaro. For individuals, this takes the form of annual self-reviews, frequent one-on-ones with managers, and regular peer reviews. Asana also works with a third party to conduct an annual employee survey, shares even the harsh feedback publicly, and commits to making changes quickly.

And, in general, there’s a “see something, say something” attitude — a value that seeing what is will help the mission, and that learning to take and give feedback well is a key prerequisite for success. It helps that all employees go through training with the Conscious Leadership Group to learn skills like holding their beliefs lightly, saying things in a way that is inarguable (with statements like “I feel” or “I’m having the thought” that are routed in the speaker’s direct experience), conscious listening, and more. Bavaro offers a concrete example of how this works in practice: “On the project manager side, part of the culture is when giving feedback on a document, rather than saying ‘Do this another way,’ we frame things as, ‘I wonder.’ When you have to reframe your thought into ‘I wonder,’ it gets you thinking about ‘What’s the assumption I have that’s different than what you have that’s leading me to a different solution?’ We find that when people hear things that way, they’re much more open to engaging with the question.”

The Asana offices provide a variety of work spaces for collaboration or a change of scenery.

Binder, the head of people operations, thinks about the culture of feedback from a recruiting standpoint. “Our employees say wonderful things about us on Glassdoor,” she says. “That doesn’t mean that we’re perfect, or pristine. What it means, what I believe that it means, is that we’ve created channels internally for people who have unhappiness to speak about those unhappinesses in a direct way. My story is, companies with bad Glassdoor ratings don’t have a safe place for people to come internally. If you looked at some of the conversations we have, there are plenty of people who are aggrieved about lots of different stuff. They just have places they can speak up internally, and we have tons of vehicles for them to do that.”

Room to Grow

All is not paradise within the company, however. For example, the company is still trying to figure out how to preserve the AOR system and make sure those internal feedback channels don’t get buried as it scales beyond 300 employees. Another clear challenge Asana faces is one common to its industry: the lack of diversity in its workforce, especially in technical positions. While its numbers of women and people of color in leadership and tech positions are mostly better than industry averages, they’re still low.

Yet Sonja Gittens-Ottley, who heads the company’s diversity and inclusion initiatives, is optimistic. “One thing we do particularly well is being comfortable talking about where we’re not succeeding,” she says — even in the challenging arenas of inequality and race.

THE BOTTOM LINE

I know I haven’t gotten a full picture of the company in just a few days, but in other ways I feel like something’s clicked, like I get what working here both asks and allows you to be. Asana’s employees, processes, workplace, and product aren’t perfect, but in the end, I realize, perfect isn’t a very useful metric for success. Who knows if Rosenstein’s vision of creating a “team brain” or enabling universal human progress will ever come true? But I’m glad people this smart are trying something so different.

As I contemplate returning home to my own job, I wonder if it’s possible for mere mortals, ones without Silicon Valley pedigrees or Facebook-sized reputations (and funding) to replicate a culture remotely as inspiring to be a part of as this one is. Two bits of wisdom keep my answer leaning towards yes. The first is something Moskovitz pointed out: the power of intention. “One of the things unique about Asana, which has made us successful building this culture, is just that we tried,” he said. Trying doesn’t take special skills or a huge budget — just commitment.

The other encouraging nugget is something Rosenstein said, when, as he gave me the tour of Agape, I fumbled with a camera on the rooftop deck while trying to hold a microphone in his face. I apologized for the awkwardness, and he shushed me. “I consider tolerance for awkwardness one of my competitive advantages,” he said. “A lot of both personal and professional relationships are impeded by people being scared of being truthful in a way that will lead to this feeling in the room of ‘Ohhhh, this is awkward to talk about.’ But if you can just stay present with the awkwardness and see it through to the other side, and remember that everyone’s on the same team, you can get to the truth. And the truth can let you go faster in whatever you’re trying to do.”

The Good Life

Of course working at Asana comes with all the perks you’d expect from a San Francisco tech firm. Here are some highlights.

Asana’s in-house culinary team prepares three meals from scratch each day for their teammates.

Meals: Healthy breakfasts, lunches, and dinners made from scratch with local and seasonal ingredients are served for free in the company cafeteria.

Snacks: Beverage coolers, snack stations, beer fridges, and more are spread throughout the office, and there is a free in-house cafe. Highlights include local kombucha on tap, rotating daily flavors of spa water, and homemade chips.

Wellness: Offerings include daily yoga, nap rooms, in-house massage and reiki, free gym membership, an up to $10,000 allowance for setting up your workstation, and 100 percent company-paid health insurance that covers mental health, fertility treatments, and alternative treatments

Time off: Employees get flexible schedules, unlimited paid time off and unlimited paid sick leave, a six-week paid sabbatical after every three years of employment, and four months of paid parental leave.

Coaching: Executive coaching is available to all employees, and all staff receives training from the Conscious Leadership Group.

Retirement: There is an Employee stock ownership plan (ESOP).

Transit: Transit, parking, or bike-commuting costs are subsidized and $50/month Uber or Lyft credits are offered.

Special thanks to Jenny Sauer-Klein and The Culture Conference for introducing us to the Asana team. Learn more about this invitation-only, two-day event at thecultureconference.com.