Blendoor At A Glance

Location: San Francisco, CA

Founded: 2015

Employees: 5

Impact: 25,000 candidates and 62 companies using the platform

Structure: Private for-profit

Major funders: Elevate Capital, Pipeline Angels, Backstage Capital, Reshma Saujani (founder of Girls Who Code), Laszlo Bock (former SVP of People Operations at Google)

Mission statement: “To drive better decisions about people based on merit, not molds.”

Tell us about Blendoor. What does it do?

Stephanie Lampkin: Blendoor is artificial intelligence and people analytics that mitigate unconscious bias, starting with hiring — which basically means that, understanding that people suck at judging other people, we are building technology that enables companies to see the true hireability of a diverse set of candidates, and we use analytics to help them identify where there may be bias happening throughout the hiring process.

We have a B2B revenue model. Companies pay an annual subscription to access the platform, which gives them the ability to integrate it with their applicant tracking systems so they can Blendoorize all the candidates that come into their pipeline. Then they can also access the diverse talent that we have in our database. They pay for different tiers based on the size of the company and the level of analytics that they want in the hiring insight.

How did you end up where you are today, and why is this specifically the business that you decided to spend all your time on?

SL: My background is a little unique for Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. I’m originally from the Washington, DC, area. My mom was homeless for a brief period while pregnant with me, so she moved up there and in with her sister who, at the time, was a computer scientist at the University of Maryland in College Park. I always tell people my first image of a programmer was somebody who looked like me, and not a white guy with a hoodie and flip flops.

That was really influential in my trajectory. I started coding at 13, was a full-stack developer by 15, got an engineering degree from Stanford, and then went to Microsoft for 5 and a half years, working with enterprise software.

I quit Microsoft to get an MBA from MIT. I started my first tech company there. That didn’t pan out, so I interviewed for an analytical lead role at Google in New York. I made it to the final round and thought it went really well, but the recruiter came back and basically said they didn’t think I was technical enough, but that they’d hang onto my resume in case some more sales- or marketing-oriented position opened up.

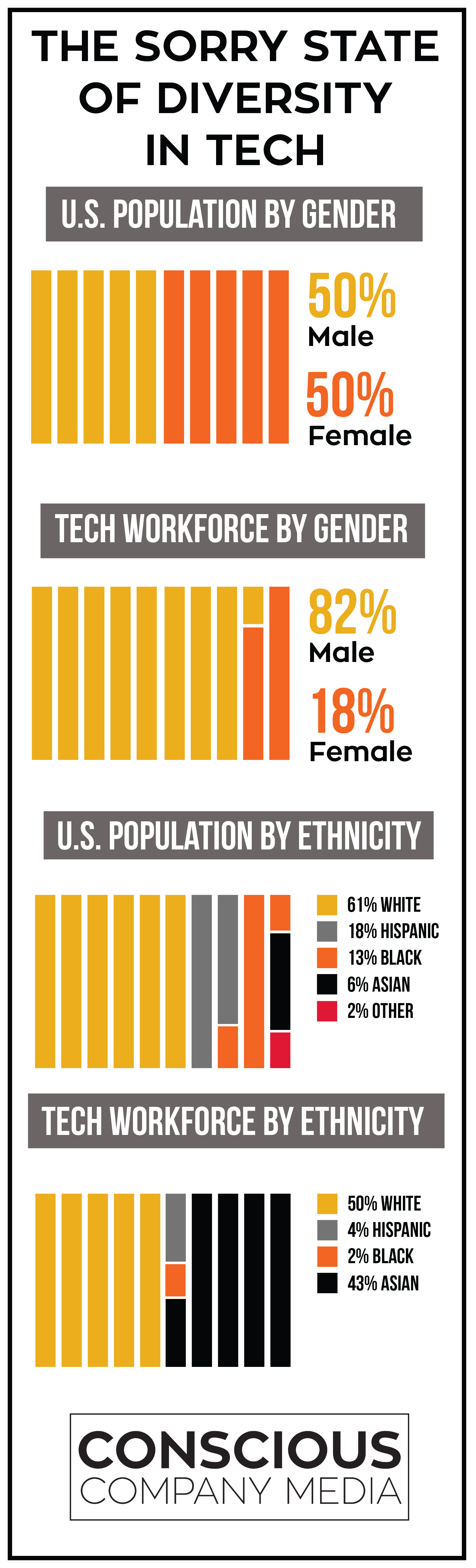

That was quite a wake-up call. I politely declined, and went back to the entrepreneurship drawing board. About six months later, Google and several other Silicon Valley companies released their diversity numbers, which were abysmal — 2 percent black, 2 percent Latino, 30 percent female. The response was, “Oh, it’s a pipeline problem. We just can’t find qualified women and people of color getting engineering degrees, learning to code,” etc., etc. Obviously, I knew that not to be the case.

I came up with the idea for Blendoor at a hackathon, and got such a positive response from it that I locked myself in my mom’s basement for two months and built the first version of the app.

Was there a specific “This is it!” moment when you had the idea?

SL: At a hackathon, you’re supposed to come up with an idea and build it on the spot. It’s not supposed to be something you’ve been working on in the past, so I genuinely went in with a clean slate. The idea was either Blendoor or to create some sort of travel repository for K–12 education, like if you were taking field trips with your class and wanted more ideas about where to go, and to even crowdfund with other schools — sort of a platform where you could facilitate that, travel for education.

It was a competition between two ideas that I was equally excited about, and of course, hindsight is 20/20. Someone told me, “Blendoor is a much better idea.” I took their advice. People came up to me after the hackathon and said, “I don’t know what you’re doing with your life, but if you build this, you could have something really special.” I’d never experienced that level of external validation with any of my other ideas before.

Tell me more about how you got the company off the ground. What were your next steps? You had an MBA at that point. Were you looking for funding as you figured out the code?

SL: I’d looked for funding with my previous startup, and I was burned out. For the most part, I just tried to live as lean as possible. I took odd jobs to eat, and my family was super supportive in letting me live without paying rent. I was literally just paying for gas and food, and focusing on learning all the frameworks I needed to build the app. I’ve been coding since I was 13, so I knew the overall practice, but I had to learn a lot of new frameworks and syntax. I was using free resources online like Lynda.com and YouTube. I built the platform in two months.

How did you go from your basement, basically surviving on ramen, to running a company?

SL: I entered a pitch competition in New York that was hosted by the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow PUSH Coalition. He’s the one that got all these Silicon Valley companies to start publishing their numbers. He was riding that wave, and had a conference in New York that was featuring a lot of executives in tech, with a focus on diversity.

One of the people there was Rosalind Hudnell, who at the time was the chief diversity officer of Intel. The reason that’s so important is that just a couple of weeks before, Intel’s CEO announced that they were committing $300,000 to improving diversity and inclusion over the next five years. They were really the first tech company to come out with such a huge pledge.

Ros had a part guiding that, and so I came up to her after her panel and said, “Hey, I have this idea…” — a real elevator pitch, like 60 seconds. She said, “Wait, you sure you don’t want to come work for Intel?” I was like, “Girl, no. You’re missing the point.” “Okay, okay. Well, shoot me an email.”

At the time, I was trying to figure out where I wanted to go. There was a female accelerator in Boulder, CO, called MergeLane, so I thought, “Maybe I need to move to Boulder.” I literally packed up my car and drove from New York to Colorado, and then Ros said she’d take the meeting with me, so I just kept on trucking to San Francisco, and haven’t looked back since.

So they funded you?

SL: They didn’t fund, but Rosalind introduced me to a ton of her other constituents. I met Facebook folks and Twitter folks, etc. Then I entered a pitch competition and won five grand. I had friends who said, “I support what you’re doing. I don’t have any money to invest, but you can crash on our couch as long as you need to.”

Basically, I just had to stretch that five grand as long as I could. I finished coding the platform in January of 2015. I didn’t get my first real investment until November of that year. I was just piecing together different pitch-competition winnings and crowdfunding-type stuff so I could eat. Fortunately, again, I didn’t have to pay rent, which was awesome.

What’s the most frustrating thing that people misunderstand about what you do —meaning diversity in hiring, tech, entrepreneurship, etc.?

SL: I try not to use the “D” word too often, because people want me in that bucket of, “Oh, yeah, you’re just trying to get people like you hired.” It’s frustrating because they associate D&I with lowering the bar, like, “Oh, we have to put these measures in place because women don’t have the qualifications otherwise.”

We mask race, gender, name, photo, and age. So, if a recruiter wants to move forward with one of our candidates, it’s more meritocratic than any other process; you don’t know the demographics of the person you like. In our branding, we’ve evolved to just emphasizing that we’re driving better hiring decisions based on merit and not mold, not that we’re driving D&I. D&I is a byproduct, not the product. That’s probably the biggest frustration I have.

I’ll never forget, I went to a women’s event in San Francisco around the time we first got started, and Dave McClure was there. Again, I ran up to him, I gave him my little pitch. I could tell that he felt like I was just building a black and brown LinkedIn. He sort of gave me a pat on the head like, “Oh, you should go talk to the Kapors” . He wasn’t taking us seriously as a real technology company.

That’s been one of the biggest hurdles that I’ve had to overcome; That’s the battle I face.

What do you do about that? How do you change it, and how do you keep from getting discouraged?

SL: We’ve buckled down on focusing on the numbers and less all the other folly. That has helped.

In terms of how do I change it, it’s this Jackie Robinson mentality of going into a domain where you are completely underrepresented, underestimated. Being 4’11” and black, and female, I’m so used to being underestimated and exceeding people’s expectations that, in some ways, it gives me an advantage. Like if you don’t expect a lot out of me and I do anything remotely great, it’s going to be perceived as that much greater. So I just want to try to keep that mentality to get through the trenches.

What’s the role or obligation of business — even a 10x tech company — in solving social problems and creating a better world?

SL: I see a shift happening in the role the private sector is having in driving major social and political issues. Having Mark Zuckerberg and all these other Silicon Valley guys step up and fund initiatives to counteract Donald Trump policies is really, really interesting to me. Even to see Sam Altman, the founder of Y Combinator, start testing universal basic income in Oakland. I think that is going to become more and more common because the distribution of wealth and capital is becoming so skewed in these tech companies.

In many ways, they are creating technology that is eliminating jobs, whether they like to own up to it or not. It’s only going to grow exponentially. It will become more and more the responsibility of high-gross startups and tech companies to recognize the impact they’re having from a social perspective, and to put measures in place to counteract it. It comes down to dollars and cents at the end of the day. If you have the resources, then you should put them in place to help those that can be your future customers or your future innovators. It’s even broader than just the moral imperative. If we want to have a society where we’re capitalizing on the talents of all our citizens, independent of gender and race and socioeconomic status, then there will be folks who have to step up and fill in the welfare gap. I don’t think the government is as equipped to do that as they were a century ago.

What are your highest values personally, and how do you act on those in your workplace and in the company you’re creating?

SL: Given the work we’re doing around bias, a lot of my principles are around equity, giving people and things a fair shake, not taking things at face value. That’s a lazy way of using our human brains, to just allow pattern-matching to make decisions for us. That’s great for certain things, but people and opportunities deserve a little bit more brainpower. I’m heavily principled on that. In terms of how that affects my day-to-day, when I’m looking at people to hire, for example, I’m super eager to source from places where folks wouldn’t traditionally look. One of my engineers is based in St. Martin. The Caribbean actually has a lot of great talent that’s overlooked; we think about India, we think about Eastern Europe, we think about South America. …

Because of what I know, and the nature of the business and our thesis, I’ve been more empowered to find the diamonds in the rough, and see things that others can’t see.

Lampkin’s trick for thriving in startup life: “habitual napping.”

How do you describe the culture at Blendoor?

SL: I would describe it as open, flexible, and trusting. Trust is huge. We really, really value having a diverse set of experiences. We have two guys, three girls. Some of us have Ivy League degrees. Most of us don’t. In that environment, trust is important because there’s external feedback that says, “Oh, because you went to Stanford, MIT, you are better equipped to lead than someone who went to a lesser-known school in the Midwest,” but that’s not true. There’s a lot of evidence that proves otherwise, but within a company, you have to have an environment that reinforces that .

You must learn and think a lot about bias, especially in hiring. Besides the obvious answer of using your service, do you have any advice for people or companies who are aware of that problem and want to work on being less biased in their hiring?

SL: It’s all about the way you perceive bias and understanding the context of when it’s okay and when it’s potentially destructive to what your goals are. I tell people, “You really have to think of it like a natural human blind spot, like you have in your car. You have mirrors in your car because you have blind spots. It’s natural. Everyone has it. No one is exempt from it. It’s just the way we’re built.”

If you think of it like that, it puts you in a different frame of mind. You don’t have to guilt anyone into trying to solve it. Then you’re more open to using tools and putting measures in place to remediate those blind spots.

The biggest advice I give to companies intent on changing is to track and measure and create more accountability for where bias may be happening throughout the organization. So many people are so confident in their ability to judge other people’s characters or qualifications that they don’t realize where and how bias happens. If you don’t have any way of tracking or measuring it, then there’s really no way to fix it. I’m big on data and accountability.

You’re an engineer so that makes sense . What’s your touchstone piece of advice right now as you’re growing as a leader?

SL: “Always be listening.” There are so many things said and unsaid when you’re managing people and making key decisions for the direction of the company. Sometimes it’s hard to see that as a leader, and sometimes it’s hard to pay attention to things that will counter your tightly held beliefs.

If you want to be successful, you have to put yourself in a frame of mind where you can see the faces around you, the people around you, things that are happening, that are guiding you. It’s a very lonely job. Sometimes you feel like you’re the only one that knows all things, but in many cases, you have people who come in and provide a much more experienced perspective, and you have to be receptive to that.

What’s keeping you up at night lately?

SL: Like most startup founders, stuff like, “Are we going to meet our sales goals and milestones?” and “Who am I going to hire for this?”

On a personal level, what keeps me up is whether the problem we’re solving I can really do in my lifetime, because it’s so deeply rooted in social tensions, racial tensions, economic history. To see things happening now, in 2017, that happened in the 1950s and 1960s is scary, just the idea that we’re regressing in some ways. I had this optimistic view as a kid that the human race is evolving, and we’re only becoming more knowledgeable about the role that women can play in the workplace and why equality is important, and why immigrants add so much value and richness to a culture. Now we see all those things brought back into question. I wonder, “Gosh, how do we really move forward when the pendulum keeps swinging, and what impact can I make with the body that I was born into?”

I draw inspiration from other folks who had to face way more challenges than I did in the past. Just keep swimming. Dory is my inspiration; just keep swimming .

What trends do you see looking ahead in hiring and in tech?

SL: In Silicon Valley, everyone is super bullish on AI , AR , and VR , all these ways that machines are going to replace a lot of mundane tasks and improve our day-to-day lives. These are marginal improvements to our existence, and oftentimes reduce human-to-human contact, which I think will have negative long-term effects.

My partner is a self-proclaimed futurist, so we debate a lot about the ethical implications of moving to a world where there’s less and less human contact. My fear is that all of this is evolving with such a homogenous group of people. There is a significant lack of diversity in San Francisco. In my day-to-day movement, I could go a whole week without seeing another African American woman who’s not homeless. That worries me.

In terms of broader business trends, I may just be in an echo chamber around this, but I see more emphasis around getting women equal pay and equal representation on boards. But we’re still relatively early in figuring out how to do that in a scalable way. There seems to be a lot of buzz around it. The fact that more women are coming forward about sexual harassment and inappropriate things in the workplace is a good sign to cut the fat, weed out the bad apples.

What do you do on a day-to-day basis to take care of yourself within the crazy founder lifestyle? Do you have commitments or habits that help you keep from going off the deep end?

SL: I’m a habitual napper. I tell people I minored in napping in college. I try, if I can, to get a good nap in every day.

Also, whenever we do business-related travel, we try to tack on some vacation, probably at least once a quarter. So I’m traveling a lot, getting to see a lot of different types of people. I think if I just stayed here in San Francisco I would go crazy, because the culture here is so different than the rest of the country.

I binge-watch a lot of media and a lot of podcasts that expose me to worlds and mindsets outside of Silicon Valley, which is helpful. We just got an Epic Pass, so we’ll be up skiing in Tahoe as often as we can make it. I just try to live a balanced lifestyle in terms of diet and exercise, because I understand the impact that can have on my psychological wellbeing as well.

What’s giving you hope?

SL: There’s a lot that’s happened in the past year that has taken away hope. What’s giving me hope? Probably just seeing the way the American people have stepped up to make their voices heard about supporting immigrants, or supporting women, or Black Lives Matter, etc.

In my 32 years, I don’t think I’ve seen that happen at such a great scale. It gives me hope. It gives me hope that there still are people in my generation, not like those in Charlottesville, but those who really, really want us to move towards a more fair and equitable society.