Many conscious business leaders are committed to fighting climate change. What these leaders recognize is that companies, through their business activities, contribute to carbon emissions that harm the environment. In fact, we all continue to learn how our collective human activities systemically contribute to climate change and harm the environment — and many of the world’s most vulnerable people.

Here’s the difference between fighting climate change and fighting institutional racism: we seem to be much less defensive about our role in perpetuating climate change. Sure, some Americans complain that they don’t want to be made to feel “guilty” about their individual choices (the car they drive, etc.), but many of us are willing to consider that while we are “good” people, we may be making decisions that are harmful to the environment. And so instead of being paralyzed by guilt, many of us have decided to change our behaviors.

Why can’t White people regard systemic racism in a similar way? That is, why can’t we recognize that well-intentioned people happen to participate in racist systems that bring harm to others? While we’re addressing our carbon footprint, we could also start addressing any “White-privilege footprint.”

But before we can consider this approach, we need to recognize that institutional racism is a problem that even conscious, intelligent White people have trouble acknowledging.

THE GREAT CONSCIOUSNESS GAP

As a progressive entrepreneur, I have been devoted to conscious business and leadership practices since the moment I learned about them. But, as a White person, one of the most challenging awareness efforts I’ve ever undertaken is to become conscious of institutional racism and White privilege.

I’ve worked in complex IT environments for about 20 years. I spend time with lots of people who are far smarter than I am. But when I ask my smart White colleagues why there are so few Black and Latinx people in most IT departments, I get blank stares. While many of my White co-workers understand intricate computer systems, they seem completely baffled by the dynamics of racism. And they typically get defensive when I bring up the subject.

For White people, White privilege is one of our greatest consciousness gaps. And the challenge for most intelligent, progressive White people is that we can concoct highly sophisticated concepts to avoid confronting our participation in, and perpetuation of, racism. This is especially true in very entrepreneurial — and very White — communities like Silicon Valley and Boulder, Colorado (my former home, and home of Conscious Company Media), where conscious business thrives.

THE GREAT WEALTH AND OPPORTUNITY GAP

America is still depressingly segregated, and since many White folks like me live in mostly White communities and work in companies with few Black co-workers, it can be relatively easy for us to keep up the illusion that we’re not individually racist.

Here’s an example. A friend of mine who lives in Boulder had a great idea for a new product. This friend walked to his neighbor, a few doors down — who just happened to be a venture capitalist — and pitched his idea. He came away with valuable guidance and a potential seed-funding commitment.

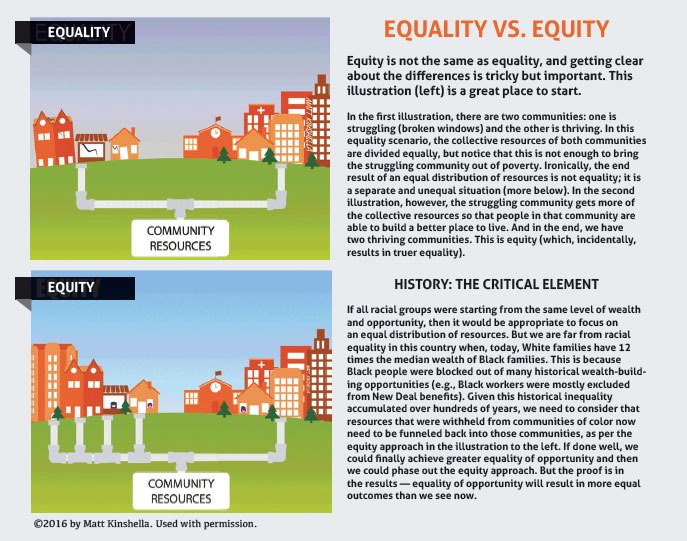

But what happens when a Black person, for example, living in a mostly Black community, comes up with a really great idea? What is the likelihood that he or she could walk down the street and find potential seed funding? Keep in mind that 82 percent of businesses start with individual savings or family-and-friends funding. Then consider this shocking fact: median White family wealth is about 12 times higher than median Black family wealth in America. As of 2016, the net worth of the median White family in the US was $140,000, while the median Black family had a net worth of $3,400. A neighborhood of Black families is therefore likely to have proportionately less in resources for helping new businesses. Black entrepreneurs do succeed in spite of all this, but how many great ideas die because of the persistent racial wealth divide in America?

I ask my White friends how they would explain the racial wealth gap, and that’s usually where the conversation ends. The truth is that 50 years after Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, racial inequity, by numerous measures, does not seem to be getting better.

Here’s the important connection: the great racial wealth and opportunity gap is perpetuated by White people’s great consciousness gap. We White folks talk about these problems as “racial inequity.” But inequity doesn’t appear out of nowhere. To say that one racial group is disadvantaged, don’t we have to admit that another racial group is advantaged? Speaking in a language that people in business can understand, every day in the country, dreams and great ideas are dying because the people who have them are not White. How can we compete, as a nation, when we’re holding back a whole segment of our society based on race?

WHITE DEFENSIVENESS

Facing such stark evidence about systemic racism, White folks, including myself, are prone to throw up our hands and retreat into our blissful privilege. We go home to our White neighborhoods and leave racism as a problem for someone else to fix.

As educator and author of “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism” Robin DiAngelo points out, one of the reasons White people get so defensive stems from the way we define racism. When White people talk about racism, we’re generally talking about individual racist behavior — individual White supremacists or individual racist police officers. Racists are “bad” people, and since we don’t consider ourselves bad (we’re conscious and spiritual!), we get defensive about the idea that we might think and behave in racist ways. This defensiveness is what’s called “White fragility.”

If you’re a White person, I invite you — in the spirit of conscious self-awareness — to pause, take a couple of deep breaths, and notice if you’re feeling defensive while reading this article. If so, I invite you to consider that this discomfort is an opportunity for personal growth.

“If we’re going to make any real progress on racial inequity in this country, White people are going to need to start getting more comfortable with being uncomfortable.”

If we’re going to make any real progress on racial inequity in this country, White people are going to need to start getting more comfortable with being uncomfortable. At the same time, we could also potentially reduce our defensiveness by expanding our definition of racism to include the institutional racism that well-intentioned people participate in.

WHAT WOULD A WHITE-PRIVILEGE FOOTPRINT LOOK LIKE?

So, let’s step back from individual acts of racism and consider the bigger picture. As an example, let’s look at Google, a powerful, affluent company with broad social influence. The tech giant is in the process of opening a new campus in Boulder, Colorado, because the city offers a population of highly educated people and a lifestyle these people enjoy. Seems like a smart business decision, right?

We can be certain that in building its Boulder campus, Google had to carry out various environmental impact studies and there were significant costs involved. Google is committed to environmental sustainability. In 2017, Google reached its goal of 100 percent renewable energy for operations, an admirable achievement.

But let’s look at this new office through the lens of racial inequity. Google — a wealthy company with an employee population that is only 2 percent Black (as of 2017) — is coming to Boulder — a wealthy city that is only 0.9 percent Black. No individual racist behavior seems to be overtly involved in this event, but by making a critical yet subtle shift from personal to institutional racism, how might our perspective change? Consider that by opening a new office in this city, it will be harder to recruit Black employees both because few live nearby and because those who don’t live nearby might not want to relocate to such a place. In other words, Google has created new job opportunities in such a way that these jobs are more likely to go to White folks for whom taking them is probably convenient than to Black folks for whom taking them is probably inconvenient.

Google’s unofficial motto, “Don’t be evil,” still appears in its employee literature. Given the company’s commitment to decreasing its carbon footprint, it isn’t unreasonable to conclude that “Don’t participate in systems that do evil” is included in that motto.

So does opening its Boulder campus inflate or decrease Google’s maintenance of White privilege? If we conclude that this event expands the company’s White-privilege footprint, then what could Google potentially do to fix or offset it? This is not to imply that Google is “evil” — this is about asking powerful companies like Google to bring the same commitment to fighting institutional racism that they currently bring to fighting climate change.

“Wait just a minute,” you — and Google — might say. “When did it become Google’s responsibility to take on the burden of fixing structural racism in America? Isn’t that the government’s job? After all, Google follows fair hiring practices; plus the company recently gave $11.5 million to organizations fighting racial injustice and inequity.”

As Anand Giridharadas recently pointed out (in a talk at Google), corporate philanthropy often creates a smoke screen that hides the ways corporations perpetuate social inequities from which they benefit. For example, companies like Google, Apple, and Amazon lobby our government for tax breaks and use tax loopholes (that their lobbying helped promote) to avoid paying taxes altogether. This handicaps the government’s ability to address big, vexing issues like racial inequity.

A White-privilege-footprint approach challenges companies to address deep, structural issues that cause racial inequity. Currently, tech companies like Google claim they want to increase their low count of Black employees, especially in higher-paid technical positions (Apple’s diversity numbers look better because of hiring for lower-paid retail positions), but they haven’t been able to break the code. If Google can create self-driving cars and artificial intelligence, then surely it can figure out how to measure and address its White-privilege footprint. It’s a matter of will.

NEXT STEPS

Here’s a sequence of ideas for how Google and other tech companies can truly reduce their White-privilege footprint. It begins by asking, in earnest, how we can get more underrepresented groups into high-paying positions, and then requires a willingness to unravel the multilayered problem of institutional racism.

1. Open IT offices in neighborhoods of color and commit to staff these offices with workforces of color. Can’t find enough qualified candidates of color? Well, that’s the common excuse used by companies who aren’t committed to racial sustainability. Companies that do care recognize that the lack of available high-tech candidates of color is an outcome of institutional racism.

2. Open low-cost/no-cost, high-quality adult technical schools in the same neighborhoods. A solid solution to the lack of qualified candidates of color is to provide easily accessible training and resources to neighborhoods of color.

3. Invest in primary and secondary schools in the same neighborhoods. Underfunded, lower-quality schools in neighborhoods of color are an outcome of centuries of institutional racism in the US. Are students having trouble attending school because they experience housing and food insecurity? Well, hopefully more of their parents can find employment at the neighborhood tech company, but if not …

4. Invest in affordable housing in the same neighborhoods. Google’s competitor, Microsoft, just pledged to do this in Seattle, which may not be individually sufficient to address Microsoft’s White-privilege footprint, but it is a good start. Now that you’ve got more Black/Latinx people in your company in managerial and technical positions, it’s high time to …

5. Move beyond standard “diversity” training and get real about encouraging White employees to recognize and work on countering their latent racism and White privilege.

Google has already taken some steps in the right direction. For example, the company opened a new office in Detroit last November, a city that is 82 percent Black (and where 48 percent of children live in poverty). As part of the deal, the company pledged to donate $1 million to help education initiatives for underprivileged youth.

If Google decides to take the idea of a White-privilege footprint seriously, they’ll ask themselves, “If the people in Detroit are underprivileged, then who is over-privileged?” So, when can we expect Google’s first annual Racial Sustainability Report to be published?

Interested in continuing the conversation on racial equity? Make sure to attend SPECTRUM, the premier gathering of multicultural changemakers creating an inclusive impact economy, June 12-13, 2019 at The Gathering Spot in Atlanta, GA.