In the grand scheme of things, there are two ways to get workers to do things: push from behind or attract from the front. Managers who choose the former stand far from the battle lines, issuing directives for workers to execute. Managers who choose the latter stand on the front line — indeed in front of the front lines, leading through the power of attraction.

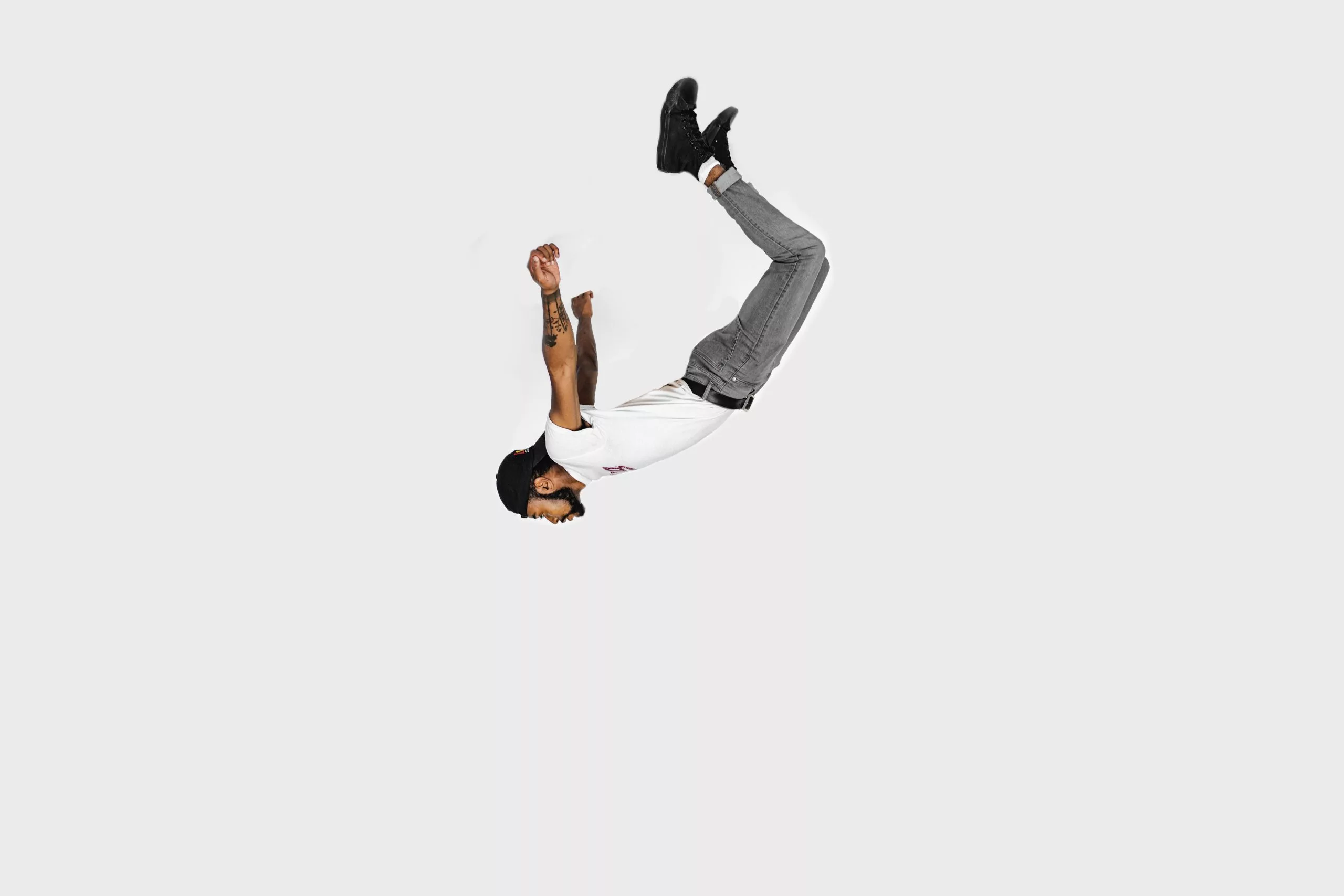

This is what I call “Management by Jumping First,” and it’s the most powerful and effective way of getting comfeartable workers — those who are either too comfortable or too fearful — to do uncomfortable things.

Courage is relative. Just as a lens can be used to magnify or shrink an object depending on the way it’s held, your perception of a situation can change dramatically based on how close to the situation you are.

There’s a vast difference, for example, between the perspectives of a high diver and the spectators in the audience. From the audience’s vantage point peering up, the big ladder stretches up a hundred feet. But from the diver’s perspective looking at the pool, it plunges a thousand feet down. The audience sits comfortably in their seats, imagining what the diver must be going through. The diver, however, isn’t imagining anything. Instead, he is perched atop a rickety steel ladder, shivering from the cold wind, struggling to contain intense feelings of fear while simultaneously concentrating on the dive. In a moment, after all, he’ll be careening toward the pool at over fifty miles per hour protected only by a bathing suit.

The most practical reason for jumping first is that it gives you a firsthand understanding about the risks you’re asking your workers to take and, therefore, the amount of courage they’ll need to meet the challenges. By experiencing the jump before they do, you’ll be able to anticipate which aspects of the challenge workers are most likely to balk at.

Just as important, by being the first up and off the high-dive ladder, you’ll gain a lot of credibility. In the same way that workers have no respect for distant managers who abide by a do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do philosophy, they hold the highest respect for managers who do the uncomfortable things they are asking others to do, first.

You’ll also reap three distinct benefits:

1. You’ll create individual views workers can use to succeed.

Managers need to provide workers with an inspiring vision of how much better things will be (for the workers themselves and for the company) as a result of their work. But it’s also essential that you provide concrete “views” — smaller and more personalized visions that enable workers, at an individual level, to have a clear line of sight between their efforts and their advancement.

This doesn’t mean you have to have the same skills as they do. Rather, it means having firsthand experience with challenges that are similar to those you’re asking them to face.

Providing workers with narrower and clearly defined views of an experience is far more useful in their daily work lives than trumpeting an ethereal company vision that will take years to materialize.

2. You’ll be seen as authentic instead of a mouthpiece.

Too often, managers are seen as mouthpieces of the higher-ups. This is validated for workers when you mimic the same phrases every other executive uses. When lower-level employees hear you talk about the “strategic value-added proposition for end users,” for example, they start to think that you’ve drunk too much of the organizational happy juice.

By jumping first, you inspire workers to value you as an independent thinker. They see that the vision you hold is grounded in real work experiences and an authentic desire to see them succeed.

3. You’ll set attitudes and behaviors for others to emulate.

It helps to lead not from where people are, but from where you need them to be. To this end, it’s useful to identify the attitudes and behaviors you find frustrating, and then be sure to role model opposite ones.

If, for example, your direct reports are apathetic, you should counterbalance their apathy by being energetic. The idea here is that, as a manager, you shouldn’t expect workers to be held to a standard by which you don’t abide. If you want workers to show more initiative, you first must show initiative. If you want them to go out of their way to understand how their work connects to a broader vision, or to have more accountability for their work, or to be more positive, you must do these things first.

Going to work with your own courage will go a long way toward getting others to go to work with theirs. Before figuring out how to get people to have the courage to demonstrate more initiative, trust, and assertiveness, first figure out how you’re going to do those things. Nothing is as powerful as modeling the courageous behavior you expect from others.