Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from “Wired to Connect: The Brain Science of Teams and a New Model for Creating Collaboration and Inclusion.” Reprinted with permission.

Today, teams power the majority of work done in organizations around the world. In fact, 90 percent of employees say they spend one-third to one-half of each day working in teams, and organizations have twice as many teams as five years ago. There is no question that teams matter. The vast majority (91 percent) of both employees and executives believe that teams are central to their organization’s success. And yet, 30 percent of employees have considered leaving their job because of negative team environments.

Teams are perhaps the single most important entity in today’s workplace: When we get them right, we can propel both individuals and the organization forward. And when we get them wrong, we can cripple an organization with dysfunction, learned helplessness, and loss of its best people.

Neuroscience is offering a surprising new understanding about what creates and destroys high-performing teams. It turns out that they are neurologically different from mediocre or poor teams — that invisible something that we feel when we’re part of a great team and know that it’s missing when we’re not. Brain science offers compelling evidence about how inclusion, trust, and purpose impact teams and how you can create the necessary conditions for true collaboration and team excellence.

Here are five things you can do to increase team collaboration.

1. Understand how collaboration differs from other types of teamwork.

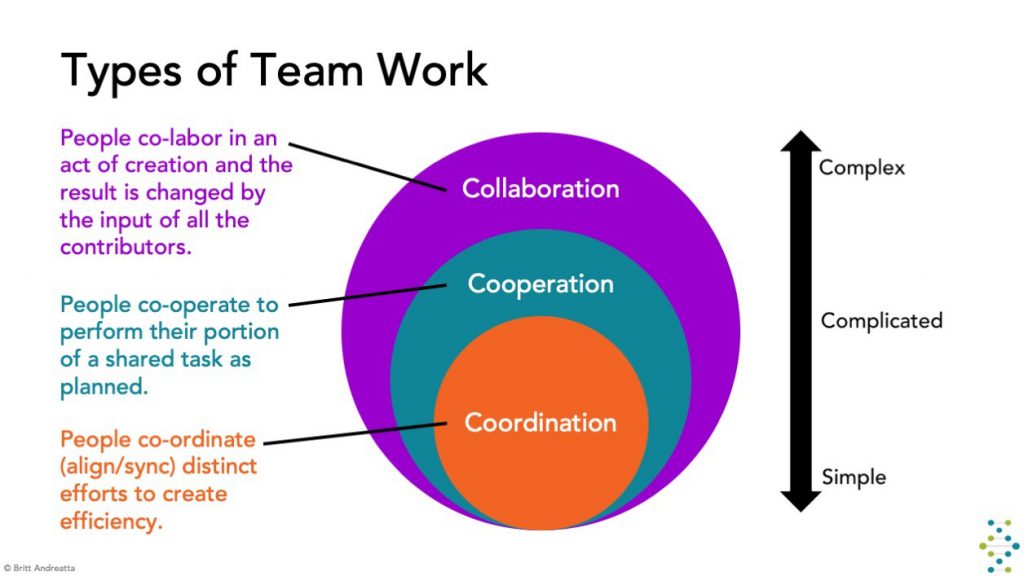

Every day, as teams work together, they are asked to move back and forth along a continuum of teamwork ranging from coordination to cooperation to collaboration. But teams are rarely aware of the differences so may not be shifting their actions and skill sets to perform their best at each type.

- Coordination is the orchestrated efforts of individuals or groups to align or synchronize their separate actions. They exchange relevant information and resources in support of each other’s distinct goals but remain independent. An example would be when the IT department communicates to Facilities that they plan on changing out computers during a certain week.

- Cooperation is the coordinated efforts of a group of two or more people to perform their assigned portion of a shared process or task. They are dependent on each other to execute a mutual objective. For example, IT relies on Finance and Shipping to ensure that new computers are purchased and delivered on time for installation.

- Collaboration is the mutual engagement of a group of two or more in a co-creative effort that achieves a shared goal or vision. They are interdependent, with each unique contribution essential to the whole. Collaboration is a special act of co-creation, and the outcomes are often both unpredictable and impossible to achieve without the individual contributions of every member. An example would be several people and departments working together to shift an organization’s culture.

While coordination only requires basic communication and planning skills (though many people still struggle with this), cooperation requires those skills plus a clear process for execution and accountability. Collaboration requires the most advanced skills of all: building trust, engaging in creativity and innovation, and having a mindful process for resolving the inevitable conflict that arises from this most complex form of work. In addition, collaboration requires special conditions that must be intentionally created and maintained if you want teams to reach peak performance.

Author of “The Collaborative Instinct” Jelenko Dragisic puts it this way, “If collaboration does not change you, then you are not collaborating. Collaboration does not come about without some kind of organizational enlightenment.”

2. Provide team training and team building

Team training should include information and skills that people need in order to team well. Things like understanding the types of teamwork, group development, work styles, effective communication, having difficult conversations, project management and execution, and how to create an environment that is safe to take risks, also known as psychological safety. This is achieved through team building, those moments designed to help members get to know each other on deeper levels and also to start building trust, a requirement for true collaboration.

In addition, team members and team leaders need to understand how vitally important inclusion and belonging are to the health of the team. Several studies show that exclusion, in any form, causes harm to individuals and can prevent a team from reaching its full potential, while belonging and inclusion drive enhanced trust, productivity, and collaboration.

3. Create psychological safety

Obviously, people need to feel safe on teams. In environments where people are physically aggressive or intimidating, a team will never achieve its stride because members will be in their reptilian or survival brains a lot of the time, without access to their higher-thinking abilities like innovation and collaboration. But perhaps the biggest aspect of safety in today’s workplaces is psychological safety. Dr. Amy Edmondson, a professor at the Harvard Business School who studies effective teams, found that, across industries, psychological safety is the key element that differentiates the highest-performing teams from the rest.

Psychological safety is not the mere absence of intimidation or harassment. Dr. Edmondson’s research showed that it’s what creates the climate for teams to do their best work. She defines psychological safety as, “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes. It is a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.”

Both team members and leaders need to know how to build psychological safety in those early meetings so that it is well established, especially if the group will be tasked with collaborative-level teamwork.

4. Design an intentional process for conflict resolution

Conflict is an inevitable part of group development and collaborative work so it’s going to happen on your teams. Make sure they’re are prepared with an agreed-upon process before issues arise. It’s common for people to get in the habit of always taking their grievances to the team leader, instead of resolving things themselves, but you want to help the group establish a mature, respectful default process for handling friction and differences of opinion. For example, they have a one-on-one conversation using tools they learned during training for having difficult conversations or they have an open forum with the other team members weighing in on the issue.

If they are not able to resolve the issue themselves, then they can come to the leader…together. In this meeting, they must share what they have already tried and why they are stuck. This piece is the game changer because it keeps the team leader from getting pulled into an unproductive pattern of “tattling” sessions. After hearing all the information, the leader provides guidance on how to resolve the issue and makes the final decision. This kind of process delineates the leader’s role as the mediator or final authority, and it sets an important expectation that your teams must be able to have frank conversations with each other and hold each other accountable. Those skills will accelerate your group’s ability to achieve true collaboration and reach peak performance.

5. Choose (or create) team leaders who have collaborative intelligence

It’s vital that organizations choose team leaders based on their skills for creating the environment for others to collaborate. This includes the new leader making the critical pivot from performer to facilitator, so they help others develop trust, engage with respect, resolve conflict,

and wrestle with the often challenging work of creativity and innovation. It turns out the best team leaders have what is called collaborative intelligence or CQ. Collaborative intelligence is the ability to think with others, valuing the diverse ways people frame questions, process information, and innovate new ideas. No surprise, the best team members also have CQ.

As Dr. Dawna Markova and Angie McArthur, authors of “Collaborative Intelligence: Thinking with People Who Think Differently,” write, “Leaders who understand and maximize the different ways that people process information are more prepared to inspire, empower, and meld the diverse intellectual assets within their organizations.” Effective team leaders know they have a responsibility to create the environment and conditions for a diverse group of members to come together to do the difficult but rewarding work of collaboration.

Regardless of industry, every team is made up of individuals who bring their own perspectives, skill sets, and experiences. Not only do team environments need to leverage the strengths of those individuals, the group needs to make its members feel safe enough to bring their best work forward. Quality team leaders understand the components of true collaboration, fostering psychological safety and good conflict resolution, and they invest in team building and team training. When this is done right, the group is set up to achieve a rarefied state of peak performance, one that is neurologically different from the rest.