In the heart of barbecue country, Marie Gibbons is reinventing meat.

“I guess you want to see the nugget?” she asks me, opening a refrigerator filled with small test tubes. Before I can answer, she pulls one out and holds it up to the light. I’d call it more of a morsel than a nugget — definitely nothing impressive to the eye — but Gibbons holds the world’s first turkey meat grown outside an animal, also known as “clean meat.”

“What will turn that into something I could eat?” I ask.

“Pouring it into a pan with some oil.”

Gibbons explained that the production process is a lot like brewing beer, but with animal cells instead of yeast cultures. In a clean environment, free from potential salmonella or campylobacter contamination, she isolated turkey cells and kept them at a temperature and pH level to match the physiology of a turkey. She fed them nutrients for a few weeks, and when she stopped they formed into turkey muscle. And there you have it: a clean turkey nugget.

“And how much did it cost to make?” I ask.

“About $300 per pound.”

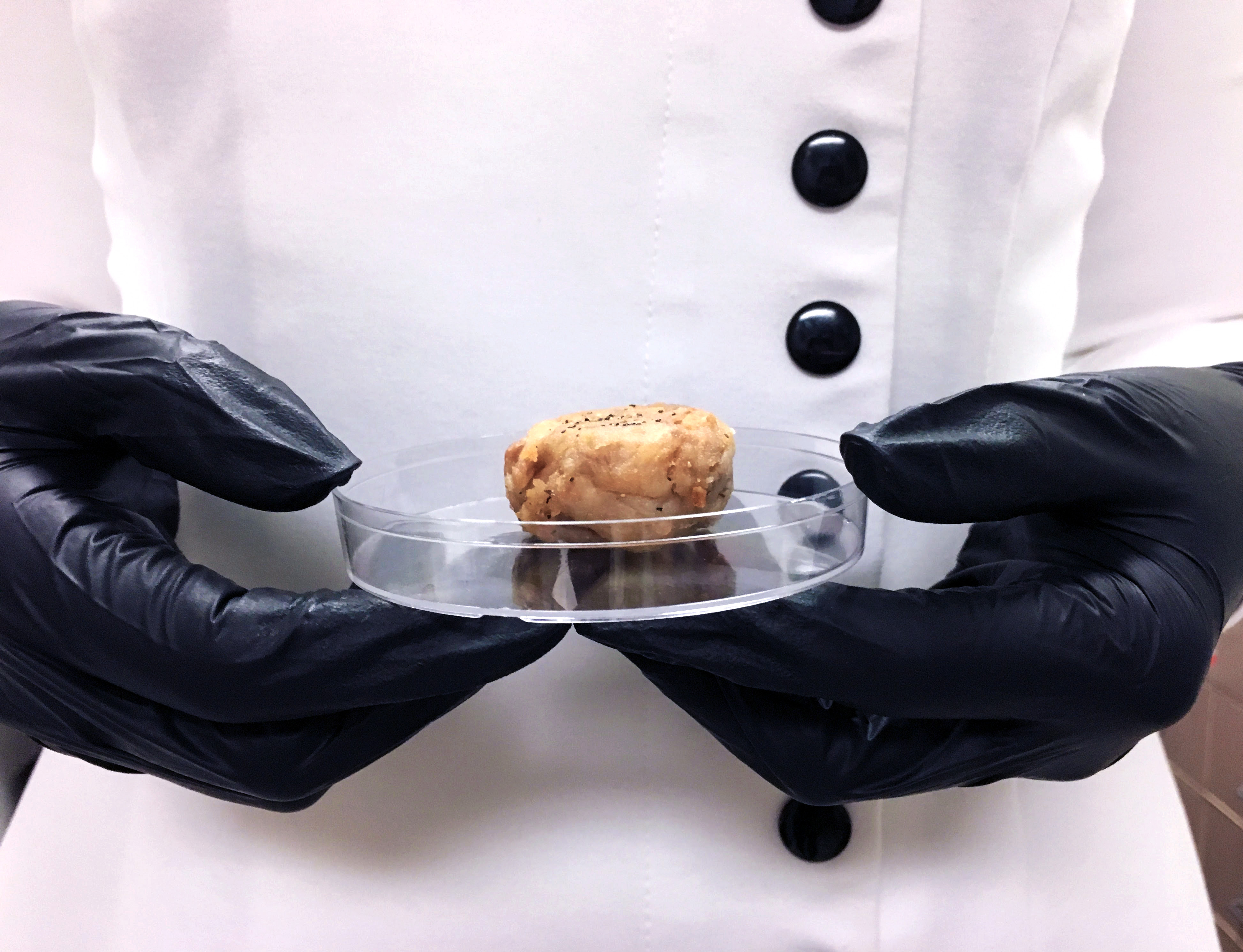

Marie Gibbons’ nugget grown with turkey cells and jackfruit (used as a scaffold). Photo by Marie Gibbons

It’s a far cry from $1.99, the US national average cost for a pound of turkey meat. Plus, as pure muscle, it lacks the connective tissue and fat that even out the flavor of a typical nugget. But Gibbons, a 26-year-old master’s student at North Carolina State University, has made a breakthrough in the effort to reinvent the $198 billion meat industry. And New Harvest, a small nonprofit, is funding her work.

Founded in 2004, New York City-based New Harvest ran on volunteer support until 2013 when Isha Datar, who holds a master’s in biotechnology, was hired as executive director. Datar’s mission is to establish the academic field of “cellular agriculture,” which New Harvest defines as “the production of agricultural products from cell cultures.” Cellular agriculture encompasses not just meat but also eggs and milk. The group even sometimes promotes the work of companies developing other agricultural products grown by cell culture, such as gelatin and coffee.

While for-profits often help nonprofits by doling out grants, sponsoring festivals, or endorsing policy, there’s a unique reciprocity in the cellular agriculture space. As for-profits in the field protect their intellectual property, nonprofits take on the task of advancing the field as a whole. Meanwhile, both work to ameliorate the environmental, animal welfare, and human health ramifications of industrialized factory farming.

In Datar’s early days at New Harvest she helped found Bay Area startups Clara Foods and Perfect Day Foods, which make clean egg whites and dairy products, respectively. Since then, New Harvest has zeroed in on funding open-source university research that for-profit ventures and other scientists can build on. The group currently funds four scientists, and their latest fellow, who aims to develop clean pork, recently began research at Kent State University in Ohio.

Growing meat may seem more Bill Nye than Bobby Flay, but Datar insists that cellular agriculture is nothing new. She rattles off examples of everyday cellular agriculture products: rennet for cheese, insulin, and vitamin B12.

“What we’re doing is novel,” she says, “but it’s also a continuation.”

Americans each eat about 265 pounds of meat a year — more per capita than in any other country. American farmers have optimized the meat production process, too: Through selective breeding, meat producers have managed to grow animals faster and fatter. For example, in 1996 turkeys weighed 67 percent more at 18 weeks old than they did 30 years prior. That optimization has given us cheap meat, but it’s come at a steep cost.

For one thing, animal farming is often cited as a top contributor to climate change. According to the United Nations report Livestock’s Long Shadow (PDF), “Globally is one of the largest sources of greenhouse gases and one of the leading causal factors in the loss of biodiversity.” Leading environmental organizations, such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and Greenpeace, have called on their members to eat less meat.

Cheap meat could also be driving antibiotic resistance. To speed up growth or prevent bacterial infections, farmed animals are fed the majority of US antibiotics. But routine use of antibiotics has led to the rise of antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.” These new bacteria strains can spread from the farm to humans, potentially rendering reliable antibiotics ineffective. Writing for Scientific American, Melinda Wenner Moyer says, “Antibiotics seem to be transforming innocent farm animals into disease factories.”

Gibbons, the grad student, worries about the many problems resulting from our high meat consumption, but she’s primarily motivated to prevent cruelty to farmed animals. By bringing clean meat to market, she says, we could remove animals from the food supply altogether.

Gibbons grew up among chickens and turkeys raised as pets on her parents’ farm in Cary, North Carolina. She remembers that some of the turkeys even imprinted on her. Her childhood affinity for animals inspired her to become a vegetarian, and in college she enrolled in pre-veterinary courses. She figured she could reform animal farming by becoming a veterinarian and instituting less cruel practices. But as she gained experience as a veterinary assistant, she became alarmed by standard farm practices, such as castrating pigs without anesthesia.

Her alarm turned to horror when a veterinarian she was working for treated a cow with a severe case of pinkeye by administering a few shots of numbing agent, slicing the eye down the center, and removing each half — a cost-cutting alternative to proper anesthesia. The cow screamed throughout the two-hour procedure.

If this grisly operation could occur at one small family farm, she thought, what must be happening to the 30 million cows at industrial factory farms? Or the over 8 billion chickens raised for meat who are hidden in windowless warehouses? Her head spun.

She quit that week. After researching clean meat online, she called New Harvest to ask how she could help. Soon thereafter the group awarded her a grant to study turkey cell culturing, and a few months later she became the first scientist to grow poultry meat from cells.

For decades, animal advocates have deployed ethical arguments. They’ve asked the public to eat less meat and vote for better laws because farmed animals feel pain and can suffer. They’ve asked Fortune 500 businesses to phase out the cruelest practices as consumers become more aware. As a result, they’ve made significant progress.

Since the early 2000s, 11 states have passed laws to phase out some of the cruelest factoring farming practices, such as confining egg-laying hens in cages so small the birds are unable to fully spread their wings. Additionally, hundreds of food industry giants, including McDonald’s and Walmart, have pledged to ban cages for the hens in their supply chains, in addition to making other animal welfare commitments. Plus, the market for vegetarian products is growing.

But by taking ethics off the table, clean meat could be a silver bullet in the fight to end factory farming. Bruce Friedrich, founder of The Good Food Institute (GFI), says the cellular agriculture nonprofit is “working to remove ethics from the equation altogether for consumers.” He explains: “Consumers make their food decisions almost totally based on taste, price, and convenience. We’re laser-focused on creating plant-based and clean alternatives to animal agriculture that compete exclusively on those three factors.”

GFI has already secured funding for 30 staffers to engage with policymakers, entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, scientific foundations, and food businesses. Indeed, some animal advocates are swapping their protest signs for lab coats. Friedrich, who spent the past two decades campaigning for animals, is their leader.

While New Harvest aims to establish an academic field of cellular agriculture, GFI aims to establish an industry. As a startup incubator, GFI connects entrepreneurs and scientists to launch new startups while supporting existing startups on branding, venture capital funding, and media strategy. The organization has worked with many companies, including Memphis Meats, a Silicon Valley startup claiming its clean meat will be commercially available by 2019. “GFI has been available to Memphis Meats for strategic brainstorming, communications support, and more from the time of our launch,” says Uma Valeti, CEO and cofounder of Memphis Meats. “We are pleased to have GFI with us on this remarkable journey.”

Impressively, Memphis Meats just completed its Series A funding round, boasting investments from Bill Gates, Richard Branson, and Cargill, the third-largest US meat processor, among others.

GFI has also promoted the work of Hampton Creek, the producer of egg-free mayo, cookies, and salad dressings that in June announced its clean meat division aims to get product in the marketplace as early as fall 2018. The company is already in talks with 10 global meat processors interested in licensing its technology.

Liz Specht, PhD, senior scientist at GFI, says the relationship with for-profits is unique but needed: “ is novel but so urgent. We could wait for all this to develop organically, but to have organizations facilitating conversations among relevant players early on makes endeavors more likely to succeed.”

Plotting the most efficient advancement of the industry, GFI recently published Mapping Emerging Industries: Opportunities in Clean Meat, an eight-page report (PDF) outlining current technology, gaps in technological development, and opportunities for entrepreneurs to fill those gaps.

“We’re trying to find the most impactful ways to move forward,” says Christie Lagally, also a senior scientist at GFI. “What kind of companies would be best to launch? What research should we try to find money for? We need to have a good understanding of the field and what research affects other research. We need to identify the right first, second, and third projects well ahead of time so we can inform entrepreneurs about what areas they should get into first.”

In coming months, GFI will release a more comprehensive report, or “technology readiness assessment.”

GFI is also responsible for branding meat grown from cell culture as “clean meat,” akin to “clean energy.” Making its benefits its namesake, not the laboratory it grows in, could be a smart move. And the clean energy comparison is appropriate: A study from Oxford and the University of Amsterdam concluded that clean pork, sheep, or beef could emit up to 96 percent less greenhouse gas and use 45 percent less energy, 99 percent less land, and 96 percent less water than conventionally produced meat.

After I first spoke with Gibbons about her turkey nugget, two New Harvest fellows taught her how to “decellularize” fruits and vegetables by removing plant cells until only connective tissue remains.

With this new knowledge, Gibbons used the connective tissue of a jackfruit — a meaty-textured fruit from Southeast Asia — as her scaffold the next time she grew turkey meat. The result? A meat-plant hybrid nugget that Gibbons says “tastes just like turkey.”

And recently, Hampton Creek grabbed headlines when it released a video with a chicken named Ian strutting around a picnic table where staffers ate nuggets derived from his cells. With its breading and plant-based filler, one of Hampton Creek’s early clean meat prototypes is similar to the Gibbons turkey nugget, but one staffer said it tastes just like meat, too.

The march toward a clean meat future is proof that when for-profit and nonprofit ventures each find their niche and plug away in tandem, progress can be faster than predicted. Just as the price of solar energy has plummeted over the past two decades, in part thanks to environmentalists, the price of clean meat could quickly drop, thanks in part to nonprofit advocates. And when clean meat becomes cheaper than conventionally produced meat, we’ll be able to have our nuggets — and chickens, too.