If you took just a quick look at his resume, you might not expect to find Jay Gould at the helm of one of America’s pioneering conscious companies. The list of businesses where he’s excelled is a who’s who of major “traditional” names like Wheaties, Colombo yogurt, Minute Maid, Pepperidge Farm, Graco, and American Standard. But Gould became CEO of Interface Inc., which designs and makes carpet tiles, in March 2017 — and is well qualified to lead the sustainability champion. His conventional corporate origins might even be an advantage.

“About 15 years ago,” he says, “I got serious about what I call the purpose-driven transformation of companies.” From within some of America’s most mainstream organizations, Gould, who started as a marketer, perfected a formula for brand success that involves investing in a mission that transcends just making money — and watched traditional success follow. His most notable win to date came at American Standard, which he rescued from the edge of bankruptcy.

Now he’s poised to help Interface make good on its commitment to inspire other businesses to make a difference in the world — with his hard-boiled credibility that’s hard to ignore. We spoke with Gould about his journey and the lessons he’s learned along the way.

Interface At A Glance

Location: Atlanta, GA

Founded: 1973

Employees: 3,278

Key Recognition: Named a top-rated leader for the 20th consecutive year in the Sustainability Leaders Survey by GlobalScan/SustainAbility

Structure: Publicly traded for-profit

2016 Revenue: $958.6 million

Vision statement: “To be the first company that, by its deeds, shows the entire industrial world what sustainability is in all its dimensions: People, process, product, place and profits — by 2020 — and in doing so we will become restorative through the power of influence.”

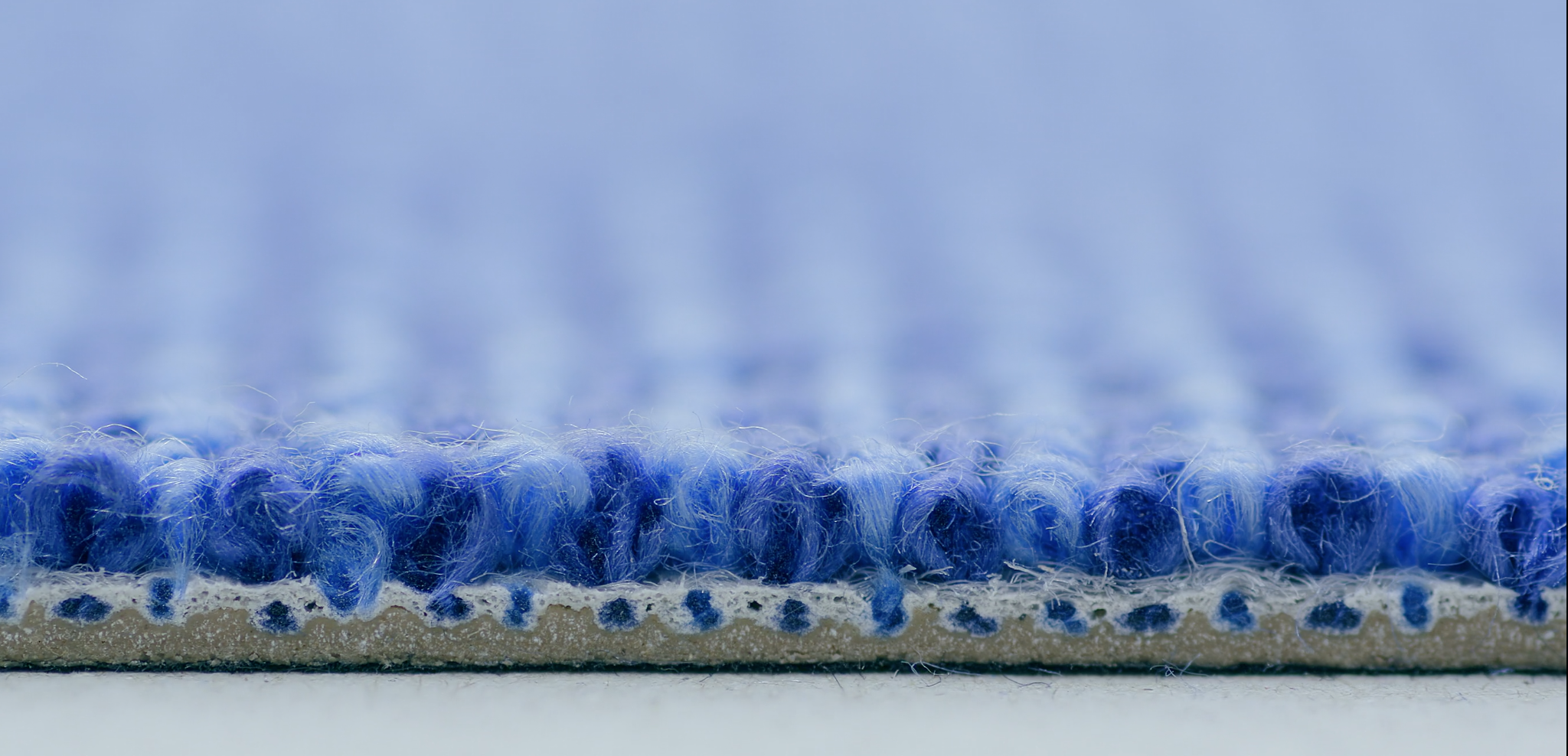

Manufacturing this “Proof Positive” prototype carpet tile actually removed carbon from the atmosphere.

How did you end up in the role you’re in today and why is that what you’ve chosen to spend your time on?

Jay Gould: I worked for this CEO, Roberto Goizueta , who’s legendary in terms of value creation in business. He used to say, “We exist to create shareowner value.” My response to that was always, “But that’s not a stirring reason to get out of bed every day.”

We want to come to work to make a difference in the world. An important outcome of the work we do has to be value creation for our shareowners, but also for other stakeholders. I became focused on saying, “We in business have to exist for a greater purpose. Can we find the way to be successful in business but also to make a difference in the world?” The second half of my career is helping companies discover that path.

How did you discover that path? What were your earliest steps?

JG: Doug Daft became the CEO of Coca-Cola at a time when Coke had lost its way. He asked a group of us to try to rediscover what made it a great company. As part of the process, not only did we explore what makes Coca-Cola tick, but what makes us as individuals tick. For me, I found it was about culture and coming to work to make a bigger difference.

Then in November of 2002 I had a lunch which changed my life, with a gentleman by the name of Joey Reiman. Joey was working on something he called the “master idea”: what is the why behind the what of a company?

I listened to Joey talk about “What’s the spark that makes companies successful?” If you go back to any company’s roots, they had to have a spark to get them started, and they usually had a founder who was driven to make a difference in the world. Almost no company starts with the idea of “Let me make a lot of money.”

What Joey and I talked about was, how do you find the truth of the company, the authentic spark, the authentic culture? I was intrigued with that idea. Joey and I started working together. We eventually started calling the work “purpose,” but 15 years ago, to use the word “purpose” in business seemed very foreign, so we called it “the why behind the what.”

I got the chance to first work on this when I was running Pepperidge Farm . There, it was about rediscovering the truth of Margaret Rudkin, the woman who founded the company in 1937. We started out with research about her, discovering the values she thought were important and resurrecting those for today’s world. I remember distinctly when I made the presentation to the president of Pepperidge Farm; I was so nervous because I wasn’t sure if I was going to be fired or move forward with the idea of how to change the culture back to its original, powerful force. With those first steps, I learned it wasn’t just the purpose itself that became so important, but also the values in the culture.

Then I joined Newell Rubbermaid, which had a whole portfolio of companies, so we really got to perfect the approach to running companies that could create value for all their stakeholders.

That work ultimately led to my joining American Standard in the beginning of 2012, because I wanted to fully enact the methodology of running a purpose-driven business in a standalone company, which is precisely what we did. When I joined Interface , it was the first time I was ever hired because of my experience with purpose-driven organizations, rather than despite it.

What are some of the lessons you’ve learned as you’ve helped transform so many companies?

JG: One of the things I’ve practiced over the last 15 years as I’ve joined different organizations is not to come in and say, “Here are the values I think are important as the new leader,” but rather, “What are the values that are authentically true to this organization?” Real servant leadership requires a leader to be authentically true to that company.

We’ve used almost an anthropological approach to not inventing but uncovering the truth of a company, and recreating that for today’s strategic environment. With that authenticity comes power.

Tell me more about what doing this uncovering work really looks like.

JG: I have a methodology behind it. Let’s say I’m coming to Interface. We started our sustainability movement back in 1994, and in 2000, we articulated a vision — we called it Mission Zero — that by the year 2020 we would have no negative impact on the Earth. As we began to talk about the next sustainability challenge to take on, what I said was, “I’m only willing to do this if we understand what was in our founder Ray Anderson’s head and heart when he articulated our first mission. What was the why behind the what?”

We brought in Joey’s consulting company, BrightHouse, and an internal team to get input from thousands of people. We interviewed employees, we interviewed customers, we interviewed suppliers, former employees. We read every word Ray ever wrote, and consolidated that into a point of view about what was in Ray’s heart.

The language we came up with was “lead industry to love the world.” Our role is to help others discover how we can help people and the planet. We put that to film. We shared it with every employee around the world. I did dozens of town hall meetings to articulate the purpose and the new mission . It was met with tears of joy, with standing ovations, and with excitement from our colleagues around the world.

Interface’s Net-Works program pays people in developing communities for old fishing nets and recycles them into carpet tiles.

Why are the roots such a powerful place to start this work?

JG: By definition, since we’re still working at the company, it worked, it succeeded. Now obviously you have to sort through all the different truths to find the ones to shine the light forward. Part of the hard work, the management part, is understanding from all the things we could choose from, from all the truths, what are the most powerful ones going forward?

Do you think it’s possible to do this kind of work where there isn’t an iconic founder to look back to?

JG: Absolutely. I did this with the brand Graco, which makes car seats and strollers. The founders were very religious, and we couldn’t use that in today’s world, being a global company. So we didn’t focus so much on the founders, but we did focus on the values that came out of that.

How do you get buy-in from employees to start shifting things?

JG: Honestly, that’s the most fulfilling part for me, because people want to work at companies that will make a difference in the world. If you do it right, it’s the easiest thing because it’s in human nature to want to help others.

Take American Standard. American Standard was a great, great company, and it had lost its way. The employees had lost some of the passion for the business because we couldn’t articulate the why behind the what.

When I got there, I was shocked to learn that 2,000 kids died the day I started with the company, and the next day, and the next day, and the next. I wasn’t aware of the global sanitation crisis, but when that was unveiled to me, I thought, “There’s a place we can make a difference. We make toilets for a living.”

I sent a small group of engineers to Bangladesh for five weeks to figure out whether we could help, unleashing the creativity of our engineers onto this problem. What we figured out was how to make the open-pit latrines people were using much safer. That was the journey to say, “Okay, there’s a big problem in the world and we can make a difference.” That notion of helping raise the standards for others became our sense of purpose, and we articulated that.

When you say, “We’re going to make a difference, we’re going to help save lives around the world” — that brings people to the office with a sense of motivation so much more powerful than previously.

Were there moments along your journey when you doubted this purpose-driven commitment was the right idea?

JG: When I joined American Standard, it was a company in crisis. It was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, and it was owned by a private equity firm with fairly short time horizons. I had to take a gamble on whether a purpose-driven approach could create enough value for the private equity holders in that short of a timeframe.

There was a moment of judgment on whether I was going to put my belief in being purpose-driven to the test at a company on the edge of bankruptcy. Obviously, I did. I believed that being purpose-driven would create the value we needed. So even in the harsh light of that financial crisis, we put money to work on being purpose-driven. And it played out with dramatic results. We quadrupled the value of the company in about a year and a half.

What have you learned about getting CEOs — when you weren’t the leader — and boards to support this kind of shift?

JG: It was hard, honestly, in the beginning. I struggled with how to get data to help support the notion of becoming purpose-driven. This is when I was working in divisions of companies, trying to convince leaders to believe in this as a methodology of running a business. What’s emerged over the last 10 years or so is an increasing belief that purpose-driven companies do, in fact, outperform their peer set.

But I would remind all CEOs trying to go through this transformation not to ask for a hall pass.

I don’t say to the board, “Let me deliver less than my peers because I’m purpose-driven.” I always go back to the adage of earning the right to pursue your purpose. Because we have a microscope placed on us, purpose-driven companies have to perform as well as our non-purpose-driven peer set.

I do try to explain some of the tradeoffs we might make. As an example, more than 50 percent of the materials we use at Interface are either recycled or bio-based . That’s a financial trade-off in support of sustainability. We’re making investments to help build recycling; we believe that will become a more profitable business model.

It sounds like it’s a question of the timeframe; that if you take a longer outlook, you can make the case.

JG: That’s exactly right. At Interface, we’ve been fortunate enough to work with a board on longer timeframes. Mission Zero was a 20-year strategy, and as we embark on Climate Take Back, we’re talking about a 30- to 40-year sustainability strategy. The board has endorsed that. We have been able to elongate the strategic conversation.

How do you start to make that shift with the board to thinking in longer timeframes?

JG: First of all, you have to recruit board members who take a perspective that purpose-driven companies ultimately do outperform their peer sets. With Interface, we were fortunate in that when Ray Anderson was still alive, he had voting control of the company. He was able to attract board members who took a longer-term perspective, and we still have some of those people today. We’ve been fortunate to weave that into the DNA of our board.

Number two, I believe it’s going to take some board governance transformation. Ultimately, business is becoming a multistakeholder-driven model. Unfortunately, capitalism took a weird turn 20 or 30 years ago around becoming overly focused on just the shareowners. In most bylaws written today, the board is solely responsible to the shareowner, and that potentially puts the board and the CEO in conflict.

Interface has a very enlightened board, and we talk about creating value for multiple stakeholders, including employees, our customers, and the environment. But boards of directors aren’t responsible for all those stakeholders. I would love to see a significant revolution around board governance.

I know there is a small movement around benefit corporations, but it’s too controversial right now. Those companies trade at a discount and there aren’t very many publicly traded companies that have announced benefit corporation status.

But I do believe there’s a movement afoot for board governance to evolve to more of a multi-stakeholder model, and there’s some research going on at Harvard right now about that. I’m encouraged that this movement will gain more and more traction over the coming decade. Those of us who are already purpose-driven can help carve the path for others to follow.

What trends are you seeing in the world of purpose-driven business?

JG: This movement, this methodology has gained so much steam over the last five years. I see it across industries. There is data to suggest that purpose-driven companies outperform their peer sets, but ultimately the leaders in an organization have to believe in this and have to be willing to make tradeoffs to take a longer-term perspective.

As an example, I’m spending $50 million to upgrade our manufacturing here in the United States, and we’ll spend at least 10 to 15 percent more because of our commitment to transform our factory into a positive member of the biosphere down in southern Georgia. I’m investing in ways to think about how we sequester carbon from the atmosphere and bring it down into our products and into our physical plants.

I also fear there is a lot of purpose-washing going on. The last time I was in Davos at the World Economic Forum, all the CEOs were talking about being purpose-driven, but sometimes you hear things like, “Oh yeah, we have to be purpose-driven so we can hire Millennials.” That just made my hair stand on end, because you have to be more authentic, you have to be more truthful, and frankly, more committed than just that.

If leadership gets it, they’re going to drive it. But if leadership doesn’t, we need the demand to come from all areas of the company. Millennials do want this, and I would encourage them to demand it, to make choices amongst employers who are purpose-driven.

You mentioned servant leadership earlier. What makes a good leader and what do you try to practice every day?

JG: The starting definition for “servant leader” is that it’s about helping others on the path to success. There’s a lot of responsibility that comes with that. As a leader, you have to be super clear about how you’re going to create value for all your stakeholders.

Having a multi-year value-creation roadmap is important. With that, you can enable freedom within an organization. Give people freedom to explore, to accomplish, to grow. Freedom and responsibility are very powerful organizational enablers. But you have to have both. You can’t have freedom without responsibility, because ultimately we have to deliver on our value-creation agenda.

That’s what I’ve tried to do with Interface: make sure both pieces are working well. The company is so committed to being purpose-driven. We perhaps weren’t performance-oriented enough, and a business needs both. Purpose and performance lead to sustainable success.

What is the role of business in solving social problems?

JG: Business is the most powerful entity in the world, and businesses need to take a long-term view about the health of the world. Despite some of the turmoil that may be happening in Washington, it’s a great opportunity for businesses to lead the dialogue.

Our point of view is that we can make a difference on sustainability, and particularly around the carbon footprint of the world. Businesses don’t all have one singular purpose, so it’s great that more and more businesses are becoming purpose-driven and collectively taking on different challenges. American Standard continues to focus on sanitation. That’s a major crisis. We are taking on global warming. We hope to help demonstrate a path forward for all business.

What’s keeping you up at night lately?

JG: This notion about reversing the impact of global warming is a huge challenge. We’re trying to find the right investments to demonstrate that reversing global warming is possible. At a recent tradeshow, we unveiled our “concept car,” if you will: a carbon-negative carpet tile. We demonstrated that it’s scientifically possible to make a carpet tile that consumes more carbon than it lets off. Now I have to make it economically viable. How’s that for a nightmare?

What’s giving you hope?

JG: My organization. The people who work for us bring me hope. As an example, we just started about a year ago on this new mission, and in that first year, the R&D team brought forward that carbon-negative carpet tile. Wow, did that give me hope. It was so exciting. The level of ingenuity that exists inside of our business just excites me every day.

More advice

Jay Gould’s Three Steps to Transforming a Business

1. Articulate a compelling purpose that can make a difference in the world.

Find the unique intersection between the needs of the world and what the company can be the very best at.

2. Find the authentic values of the company.

You need to be able to guide the behavior of the organization, but we didn’t sit in a room and invent values for our employees to live by. We went back to the original roots of the company and rearticulated the values that guided the company’s development from the beginning.

3. Make a plan to create value for all stakeholders.

One of the things I constantly remind organizations is, “You have to earn the right to pursue your sense of purpose.” You earn the right by delivering good financial results. Because if we ignore those things, we actually won’t have access to capital to allow us to invest in the business. We don’t come to work fired up every day about our financial results, but they’re a super important outcome of the work we do so we can continue to pursue our purpose.