Read or listen to this story below.

She waited until she was sure everyone had gone home for the weekend. Soon her office bore no sign that she had ever worked there. Next to her keys, she left a note on her desk so they wouldn’t try to reach her. She knew she was severing her relationship to these people forever; she hadn’t even given her work friends a chance to say goodbye. They would simply find her note on Monday and realize she was gone. But that didn’t matter to her; she just absolutely could not spend another day in this job. She turned off the lights and drove out of the parking lot into the Michigan summer. She wasn’t the first manager to become fed up with the company’s culture and suddenly leave; just the latest.

It was 2014 and Biggby Coffee was on track to bring in $83 million in gross revenue. In less than two decades, co-CEOs Bob Fish and Mike McFall had grown the coffee franchise from a single store near the campus of Michigan State University in East Lansing to more than 200 stores across nine states — and there was no end in sight. Annual growth had hovered around 20 percent for a decade. A few years before, the company had achieved its early vision of becoming one of the nation’s three largest specialty coffee franchises. The company tagline explained the philosophy Bob and Mike tried to infuse in the business: Be Happy, Have Fun, Make Friends, Love People, and Drink Great Coffee.

The company began when Bob’s desire to own a restaurant and maybe a franchise aligned with his affinity for good coffee. In the mid-1990s Starbucks was a force on the rise, and Bob saw a market opportunity. He opened his first coffee shop on March 15, 1995. Shortly after that, Mike was hired as a barista and Bob heard that Mike might be a good candidate to manage a planned second location. The two met to talk about the idea on a gorgeous spring day and decided to go for a walk rather than sit inside. Two hours later, they were no longer talking about Mike managing a second location; they were agreeing on terms for creating a new company committed to growing the brand. A handshake sealed the deal, and suddenly, they were partners.

BIGGBY COFFEE At A Glance

• Location: Headquartered in East Lansing, MI

• Founded: 1995 (began franchising in 1999)

• Team Members: 63 in the home office

• Traction: 260 stores in 9 states employing about 2,800 people

• Structure: Private for-profit

At first blush, they seem like an odd couple. Bob is clean-shaven and wears a black T-shirt and jeans more days than not (adding a hoodie when the temperature drops). Mike strokes a full, well-groomed beard and is a fan of sport coats, loud pants, and louder socks. Bob grew up in a dozen places in Europe and beyond. Mike grew up in Milford, a small community in suburban Detroit. Bob can’t land a sports analogy to save his life. Mike loves sports, even inventing new ones like a devilishly fun variation of table tennis he calls sting pong. But despite all of their differences, they made a powerful team.

They are also, however, alike in some important ways. They once participated in an exercise with a group of their franchise owner–operators in which a facilitator gave everyone a deck of 50 cards listing possible life priorities such as trust, health, or money. First, each person quickly chose their top 10 priorities and discarded the rest. They then chose the top five, three, and finally the top two. Though seated on opposite sides of the room, Bob and Mike kept the same two cards for their top priorities in life: loyalty and legacy.

For both men, legacy meant building a great company, one that’s both huge and good for people. Biggby’s growth rate had them on track for achieving the huge part, and to work toward the good for people part Bob and Mike deliberately designed what they considered to be a very progressive workplace. The corporate office was outfitted with video games, a room full of bean-bag chairs, and a fully stocked Biggby cafe, helpful for training but also open for anyone to make any drink they’d like, for anyone. They were most proud of a sabbatical program to reward loyalty: for every five years of service to Biggby Coffee’s corporate office, employees got three paid months off to do whatever they wanted.

Mike McFall (left) and Bob Fish share a commitment to the core values of loyalty and legacy.

Bob and Mike had led Biggby through survival mode to stability to aggressive growth, but they began to realize they had done it by being autocrats. Their track record of success had taught them that they were uniquely capable of calling the shots, and they insisted that every decision had to go through them. But as they moved deep into the company’s second decade, it was becoming clearer to both that a legacy that dies with you is not a legacy. They needed to build up a leadership team that could run the company without their direct involvement.

A legacy that dies with you is not a legacy.

So Bob and Mike built a walled-off private suite in the office in an effort to force people to take questions to a manager or director, not to the CEOs. They further limited access to themselves by staying out of the office altogether several days each week. But unlike at their franchise stores, Biggby had never created formal training systems and protocols for their corporate office. They hired people on personality and threw them into the proverbial deep end. Those who could swim stayed and were likely to be promoted. Those who could not swim left.

Bob and Mike did not make it easy for employees, and they knew it. Those who survived grew thick skin. But Bob and Mike were loyal to people. Unless someone had a hand in the till, no one was ever fired. So when they discovered another unexplained management departure that summer day in 2014, their response was, “I wonder what’s the matter with her!”

In an unguarded moment, the leaders might have confessed to a suspicion that something was wrong with their company culture — that despite the impressive performance, the wheels might be coming off the bus. But in the Biggby office, there were no unguarded moments.

♦

In October 2014, Mike took a weekend camping trip to nearby South Manitou Island with his brother and son. After a day of hiking sand dunes and relaxing on the beach, the party settled in for dinner around a campfire ring that served several sites. Before long, a couple from a neighboring site joined them. In the first few minutes of pleasantries, Mike remembers learning that the woman was a lawyer and the man was “some kind of consultant.”

When the conversation turned to workplace culture, Mike started listening carefully. The consultant talked about a group of companies that had outperformed the S&P 500 by 14 to 1 over the previous 15 years. They had done it in part by demonstrating deep care for their employees and other stakeholders and by pursuing a clear purpose beyond profit. As Mike listened, he learned about a bread company that was helping former inmates successfully rejoin society, and manufacturers that were helping their employees become more emotionally intelligent, measuring things like divorce rate in addition to how many widgets were made each day. He heard the case for how it makes business sense to offer people real meaning through their work, increasing engagement and productivity. He also heard about how positively it affects the legacies of companies that aim for such a high bar.

That night, Mike lay awake in his sleeping bag. He thought about his and Bob’s beginnings with those first stores, about the unlikely success of a couple of class clowns who had both been told repeatedly that they would never amount to anything. He thought about how proud he was to prove his teachers wrong. He’d shown the world that you don’t have get good grades and work your way up some corporate ladder to find success. He had proven, at least to himself, that success could come from following passion and desire, and doing cool shit. He was even pretty sure that following his passion hadn’t just been an alternative path to success, it might just be the key to success. But he had been beginning to suspect that at some point, adding another increment of income to his tax return could no longer be called “doing cool shit.” At some point, that probably had to be called “greedy.”

Mike reflected on Biggby’s higher purpose. He and Bob had already achieved their vision of becoming one of the biggest specialty coffee franchises, and they had never set a new one. Mike had a very clear personal vision: to become the owner of the Detroit Red Wings. But something was gnawing at him. Compared to the examples he’d heard that night, his vision and any future growth target for Biggby felt hollow. What could Biggby do that would change the world?

His vision and any future growth target for Biggby felt hollow. What could Biggby do that would change the world?

The next morning, Mike gave the consultant a business card. When they connected again by phone a few weeks later, he ended the call after only 15 minutes: he was in. He just needed to get Bob on board.

Bob met Mike’s enthusiasm with his usual cynicism. Bob would not have described himself as warm and fuzzy. He had a chip on his shoulder for “tree huggers” and “the twigs and nuts crowd,” and this culture and purpose stuff had the same smell. Still, he trusted Mike, and consented to undertaking a culture assessment to see how Biggby was performing in the eyes of its employees and other stakeholders. The process began, and Bob and Mike braced themselves for the results.

♦

The report arrived in Bob and Mike’s inboxes in February of 2015, and it pulled no punches. The employees in the corporate office reported that any error or a failure to reach the same conclusion as the CEOs was met with F-bomb–laden tirades; verbal abuse; harsh dressings-down; and occasionally, thrown objects and punched walls. The analysis revealed a toxic lack of care and appreciation. It uncovered a pervasive sentiment of being undervalued and underpaid, and it included scores of scathing direct quotes from employees:

“Working at Biggby … is like an abusive relationship you can’t get out of.”

“Biggby is a Jenga tower built on a single brick foundation, and it’s at risk of toppling over.”

“The level of stress is so high that ‘Be happy’ has become a sarcastic joke in the Home Office.”

The report concluded by recommending leadership training for Bob, Mike, and four key director-level employees, plus creating a new employee committee to improve the company’s compensation structure. It also recommended that Bob and Mike read the worst parts of the report out loud in front of the staff to let everyone know they had been heard.

When Mike first read the report, he set his glasses on his desk and wiped tears from his eyes. He could not believe he was leading a company where people thought those things. It was the hardest thing he had ever had to read. When they discussed it, Bob and Mike realized they faced two options: throw the report in the garbage and carry on like it had never happened, or embrace its recommendations and the chaos that would follow. They both agreed that the right thing to do was clear, and that the right time to start would be at the monthly staff social the following Friday.

Staff socials were mostly designed to help employees have fun and blow off steam. Departments took turns planning activities and games, and usually, only 30 minutes were reserved for work discussions. So it was that an office full of more than 50 people, with their hearts still pumping from a silly game, abruptly had their anonymous words read back to them by the very people they had not dared tell how bad the situation really was.

When Bob and Mike finished speaking, the silence was deafening. There is power in saying things out loud and committing to something in public. For Bob and Mike, a weight had been lifted and it felt good — like when someone finally admits to being an alcoholic. The leadership team was shocked that it was all out in the open. No one knew what was about to happen, what change would look like, or how long it would take. That was particularly true for Bob and Mike. At that moment, only one thing was clear to them, and to everyone in that room: the genie was out of the bottle and there was no putting it back in now.

♦

Bob and Mike immediately relinquished their unilateral decision-making authority to a new leadership team consisting of themselves and the four director-level employees. The leadership training began the following month, with the consultant observing their meetings and sending the group detailed notes on how they had each performed. The group also read “Multipliers,” by Liz Wiseman, a careful study of leadership styles that either diminish or multiply the intelligence of a team. The book helped Bob and Mike see the dramatic impact they had on people. They had never considered that by behaving as if their opinions were the only ones that mattered, they had ensured that they would never get any pushback, discussion, or free thought in their company.

To their credit, they changed quickly; almost overnight, they went from command-and-control to saying virtually nothing in meetings. But a long history of dysfunction doesn’t just disappear, and deep trust issues still plagued the team. The co-CEOs’ new silence was agonizing for everyone, as the four directors attempted to fill the void while keeping a nervous eye on Bob and Mike like gazelles in tall grass watching for the slightest sign of danger. They had traded one form of dysfunction for another.

Biggby Coffee changed its name from Beaner’s Coffee in 2007; the name “Biggby” comes from a description of the logo — a “big B.”

Next, the group read Simon Sinek’s “Leaders Eat Last,” which focuses on creating safety and driving fear out of the workplace. The best way to do this, Sinek argues, is to build relationships with people as people and not just as employees. At the time, Bob and Mike didn’t know most employees’ names — they believed that was for someone else to know. Your team, your people was the unwritten rule, and Bob had become a master at the quick, nameless greeting as he passed people in the hall. Mike began to call directors and others in a deliberate effort to build relationships, but people on the receiving end of these calls were highly suspicious of his motives. Bob’s efforts to improve communication and trust met people unwilling to give straight answers because they feared consequences for admitting a mistake. Signs of progress were scarce, but the study had given Bob and Mike a new vision for what they could build, and they wanted it more than ever.

The leadership team also experimented with two practices that began to show promise. The first was a personal high/low check-in at the beginning of meetings, an effort to get to know the personal ups and downs that were happening outside of the office. They started timidly, but before long, some of the leadership team shared deeply personal struggles, demonstrating vulnerability that made it safe for others to let down their own guard in turn. The second practice was to reserve a few minutes at the end of meetings to debrief. This created an opportunity to express feelings and resolve frustrations in something closer to real-time. There were plenty of frustrations, but with the consultant watching their every move, the team worked to stay on their best behavior. It was very intense, but old ways of relating to each other were giving way to a more authentic connection and, to the leadership team at least, the personal growth of each team member was obvious.

The leadership team also read “Everybody Matters,” by Bob Chapman and Raj Sisodia. The book profiles a company that buys struggling manufacturing firms and turns them around almost exclusively through culture transformation — without firing anyone. One passage in this book hit Mike particularly hard. It describes CEO Bob Chapman’s awakening to what he calls “the awesome responsibility of leadership to care for the lives entrusted to you as though they were family.” Mike realized that he would never have treated his children the way he treated people at work, because he cares about his children’s emotional stability and development. He cares about them growing and learning. He loves his kids. Mike would never before have said that he loved somebody at work, but suddenly, that changed — and so did the way he treated people. He began to see that the future of his people was the future of his company — and his future too.

Mike would never before have said that he loved somebody at work, but suddenly, that changed — and so did the way he treated people.

Mike began experimenting with a practice he had never tried before: telling people they were doing a good job. He thought of the way he’d taught his son to walk, not by yelling at him and calling him stupid when he fell, but by encouraging every shaky step. Mike watched people light up as he offered them even minor praise, and it quickly became a highlight of his role.

Slowly, things began to improve. Mike’s phone calls with employees became more normal, and not only did people pick up more regularly, but he also thought he could hear the beginnings of warmth on the other end of the phone. As for Bob, after a period of providing constant reassurance to people that their jobs were not in danger and that he was just trying to get to the truth, he was catching glimpses of honesty and transparency. One of the directors even confessed that despite having built a strong relationship with Bob and Mike, he had been fearful that he could be terminated at any time. He had been living with that fear for 15 years, and after months of participating in the leadership training, he finally felt safe enough to risk saying so.

♦

Six months had passed, and while the management team was still in the thick of finding a new way to lead together, the employee compensation committee had stalled after some initially impressive work redesigning the company’s system for promotions and raises. The group had many detailed questions about how the compensation budget Mike had given them at the beginning of the process was calculated and what might happen in a variety of future scenarios. In short, the committee wanted to see the company’s full budget and understand how the total expenditure on salaries and benefits was calculated.

Mike had always believed that companies should be transparent because the more people understand the finances, the more motivated they are to keep costs down and revenues up. For its first few years, company management had proactively shared the finances with employees so they would know what was happening. As the company grew, though, that transparency began to feel awkward because of how much money Bob and Mike, the sole owners, were making compared to everyone else. So with no official announcement or formal policy change, Mike simply stopped sharing, and soon the budget became his sole domain. Anyone wanting to spend a dime on anything had to get his approval, and he said no to virtually everything.

Mike had always known that he would eventually open the books up again. After all, if you’re a big public company, you have to disclose all of that stuff anyway, and Mike wanted to build a big company. But Mike was understandably conflicted about the committee’s request. On one hand, the direction the culture was heading seemed to demand transparency, but on the other hand, his and Bob’s total compensation had never been higher. He was also concerned that people wouldn’t understand the way an organization’s value is measured — that you can’t grow a company and not grow value, and that value is all about positive cash flow. Were the employees ready for this kind of information? Mike decided that the long-term benefits outweighed the short-term risks, and he stayed up late for several days preparing a detailed presentation to help the staff understand what he was about to share.

Biggby Coffee has stores in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, South Carolina, Wisconsin, Kentucky, Florida, and Texas.

At the August 2015 staff social, everyone in the corporate office, from the directors to new hires, crowded into the big, colorful meeting room. Mike stepped onto the small stage at the front, cued up his presentation, and began to show them everything. He revealed how company revenue was spent across all categories. He walked everyone through the investments in benefits from medical insurance to the in-house cafe to his prized sabbatical program. He laid bare the salaries of directors, managers, supervisors, and entry-level staff in each department, and he revealed the sizeable amount left over for the co-CEOs.

When the presentation was over, Mike drew in and held a nervous breath and scanned the room for the criticism he expected would follow. He opened the floor for questions. But there was no cascade of comments, angry or otherwise. As the meeting adjourned, he found himself bewildered and frustrated. He had exposed himself and there had been no discernable reaction. Desperate for feedback, Mike pulled aside a director who had been with the company for more than a decade to ask the question at the root of his anxiety: “What does that total compensation number for Bob and me mean to you?”

“Nothing,” said the director. “I would expect that the guys who founded a company of this size should be making a ton of money. And I think the rest of the world would expect that too.”

Mike felt a wave of relief course through him. Over the next 24 hours, the relief blossomed into liberation. The budget was not his burden to carry alone any longer. After the move to transparency, Mike observed no negative consequences. There was no drama over who was paid what. But the transparent budget did produce positive consequences for the company. The most immediate benefit was empowering the compensation committee to complete its work and prepare its recommendation, which would have to get through the leadership team for final approval.

One October morning in 2015, a nervous compensation committee filed into the conference room that had borne witness to the worst of Bob and Mike’s behavior over the years. They had rehearsed their presentation over and over to make sure they had an airtight proposal, battering each other with questions in their best old-school Bob and Mike impressions. They felt that they had to get this right — the entire office was counting on them.

The leadership team had also spent time preparing for the meeting. They felt tremendous pressure to accept the compensation committee’s plan and feared what would happen to the culture (and the company) if they could not. Everyone tried to hide their nerves as the door clicked shut behind them. Conversations in the conference room were inaudible to the rest of the office outside — unless, as was common in the past, someone started shouting.

When the committee’s presentation ended, there was a long moment of tense silence. Mike broke it with carefully measured words. He told the committee that he could not recall, in all his time receiving employee presentations, an occasion before — ever before — on which a group had done such impeccable work. While the proposal involved a significant increase in the overall cost of compensation, he, for one, was quite comfortable approving it as it stood, with no modifications. The rest of the leadership team concurred. A sense of relief and triumph filled the room and spilled out to the employees waiting outside the glass windows doing their best to look disinterested in the proceedings. The details of the deal were shared the following week at the November staff social and a new compensation structure took effect on January 1, 2016.

It was a quantum leap for the company. The new compensation structure not only provided evidence to the staff that they had a real voice in changing things for the better, but the process of debating it had dramatically increased the financial sophistication of the office. Employees who came into the process feeling they were entitled to bonuses and raises were now savvy stewards of company finances, and they were eager to educate their peers when necessary. Most important, it was proof that the new leadership style could produce a result for the company that was better than what Bob and Mike could do alone.

♦

The anonymous culture survey that had made Bob and Mike face the truth in 2015 was repeated in the spring of 2016 and it showed substantial improvement. There was plenty more to do, but the cultural detox was working. It had been 18 months since Mike wrestled with Biggby’s purpose in his sleeping bag on South Manitou Island, and it was now time to focus on defining one.

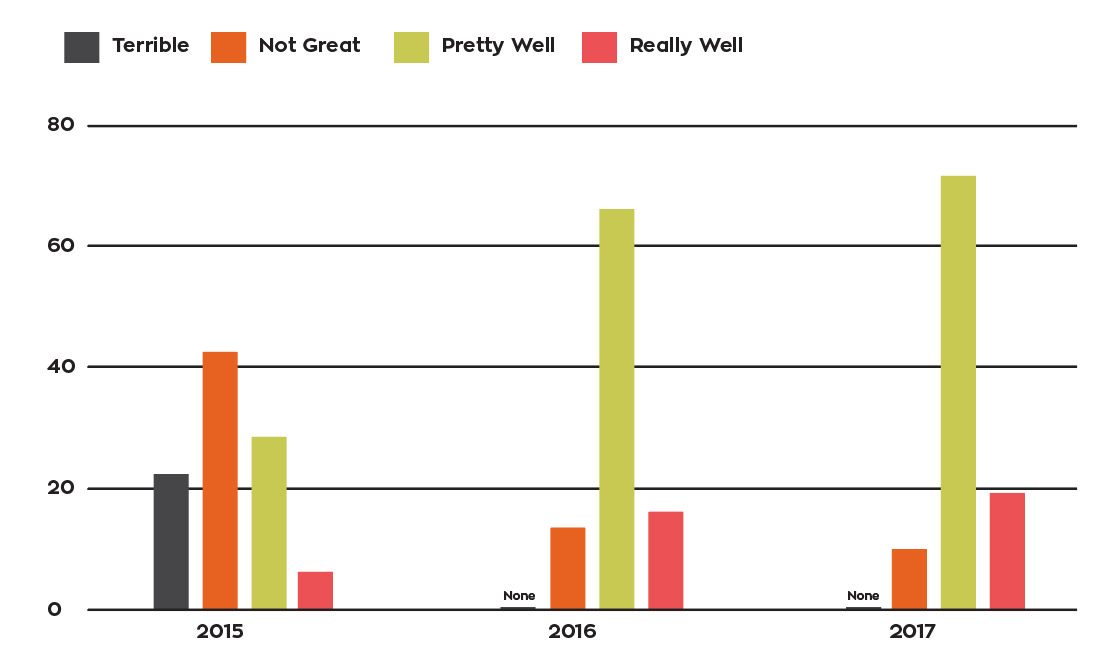

Biggby’s Culture of Change

The results from three years of culture assessments asking the question, “How well does Biggby Coffee treat its employees?”

The process began in July of 2016 and it was maddeningly slow. The leadership team opened a full hour during its weekly meeting for the conversation about purpose, and dozens of staff members attended and engaged in deep philosophical debate that left their brains hurting. Again and again, meeting debriefs revealed frustration that just as progress seemed within the group’s grasp, the meeting had ended. This went on for months, but even as the purpose process appeared to be getting nowhere, it was creating some unexpected benefits.

Mike was surprised to find that the process of discussing their purpose had finally created a structure for people to disagree with him and push back firmly. Mike and Bob had learned to want a team that would challenge them, and in the purpose meetings that team began to show up. Once it happened a few times in purpose meetings, people felt safer disagreeing in other meetings, too.

As the heat of summer gave way to the brilliance of fall, a new company purpose began to emerge: “Biggby Coffee Exists to Support You in Building a Life You Love.” The phrase itself didn’t take long to gain support, but the nettlesome question was how to define “a life you love.” The debate eventually refined four essential components: 1) a sense of belonging, 2) emotional and physical vitality, 3) knowing who you want to be, and 4) being able to exceed your basic needs.

Articulating the components of “a life you love” was one thing, but measuring them was another, and in order to be operationalized, a purpose must be measurable. So the debate continued, once per week, an hour at a time, as the leaves fell and the frost came. Finally, the leadership team settled on indicators they could use to measure each of the four elements through a self-assessment. For example, they would score a person’s self-reported sense of belonging in relationship to family, friends, and work, and they’d evaluate exceeding basic needs by determining whether a person invests 10 percent of their income for their future.

The self-assessment was the key to operationalizing the purpose. The leadership team planned to use the self-assessment to help Biggby Coffee stakeholders look at their own lives and identify specific areas for improvement. Biggby would then use these results to develop practical tools to help people improve their scores, thereby supporting them in building a life they love.

Articulating the components of “a life you love” was one thing, but measuring them was another, and in order to be operationalized, a purpose must be measurable.

It had taken six months, but when the leadership team officially adopted the purpose in December 2016, Bob and Mike were very proud of it. It felt good to say it out loud, and it would give people a compelling reason to show up to work besides the paycheck. And for Mike, it finally answered the question he had wrestled with: What could Biggby do that would change the world? Mike believed that the self-assessment would help unshackle people and get them to trust themselves to work on what they dreamed they could do. Having that kind of an impact on the more than 2,800 high school and college-age baristas across the Biggby system, not to mention all of Biggby’s franchise owner–operators and other stakeholders … that was the grandest purpose Mike could think of.

Up to that point, Bob wouldn’t have said he was just role-playing in the culture-change effort at his company. He understood the training materials and he had been an active participant in the transformation process from the beginning. But it wasn’t until more than two years after Mike’s fateful camping trip that Bob experienced the promise of the purpose his company had just adopted.

As the self-assessment was being finalized, Bob found himself reading the projector screen full of questions that everyone in Biggby Coffee would soon be asked to answer, and mentally responding as he read. The first section of the self-assessment was “a sense of belonging” and it drilled into specific areas of life.

Work. “Sure, I belong here,” Bob thought — but then, he was the boss and it was possible that he had built this world to suit his personality, so maybe that didn’t count.

Friends. Of course Bob had friends, but the question called to mind a surprisingly thin Rolodex of relationships deep enough to feel like belonging.

Family. Well … Bob’s thoughts drifted as the discussion continued around him. His childhood had unfolded as his family moved 13 times in 17 years. He had learned early to build an emotional wall around himself for protection against the pain of leaving people behind again and again. In time, the wall protected him from everyone.

Bob’s father, who lived in San Diego with his second wife, would call on occasion and suggest that they take a vacation somewhere with their families. “Not a chance,” Bob always thought. Bob’s brother lived in Berlin, and Bob lost no sleep in between rare updates from him. Bob’s mother lived in Pensacola, Florida, and Bob, consciously or not, leveraged geographical distance as an excuse for limited engagement.

Still, when Bob permitted himself a moment of sentimental reflection, he realized that he had never experienced the warmth of an extended family, and now that he was married and the stepfather to an incredible son, he wanted to — for his son’s sake as much as his own. As Bob pondered the self-assessment section on belonging, a realization dawned on him: his father, his brother, and his mother couldn’t all be separate causes of his lack of belonging in his family. No, it couldn’t be them. “It must be me,” he realized.

Bob didn’t say anything at the time, but he had felt the power of the tool his team was creating. It was the moment Bob Fish went all in. The meeting ended and Bob went back to his office and closed the door. He knew what he had to do. He sat at his desk for a moment, took a breath, and reached for his phone.

♦

One morning in early December 2017, the employees of the Biggby Coffee corporate office received an all-staff email instructing everyone to report to the big meeting room for a mandatory special meeting. No one had ever seen anything like it. Not since Bob and Mike had read the survey results during the staff meeting nearly three years before had the tension in the building been so palpable. The room filled quickly, and after extra chairs had been found, the four directors took the stage. Their words sounded rehearsed as they explained that in another room, six people, 10 percent of the team, were being laid off.

The team explained that they had built the 2017 budget based on a 16 percent growth target, and spending followed suit, but by the middle of the year, growth had slowed dramatically. A series of factors had contributed. For one, out of loyalty to their Michigan owner–operators, Bob and Mike had led a charge to temporarily close the Michigan market to new stores. There were still overall performance issues in the corporate office. And yes, the time invested in fixing the culture and defining a purpose meant there was less time for everything else.

Bob and Mike had seen the problem emerging that summer and had tried to fix it with tactical financial cuts, but by year-end it was clear that their efforts had not been enough. Growth would be just north of 7 percent and projections showed a $250,000 loss in the first two months of 2018 alone. Bob and Mike had shared this information with the leadership team several weeks before. In a franchise’s corporate office, budget cuts mean layoffs — there just isn’t anything else to cut.

Layoffs had been necessary only twice before in the company’s history. The first time was early on, when the first and only store was seeing just four customers an hour. Bob had emptied his savings, maxed out his credit cards, and sold his car to try to make it work, but it hadn’t been enough. The second time was when growth stalled roughly 10 years later. On both occasions, when people were cut, they’d get walked out and no one would talk about it.

This time was different. The leadership team had agonized over what to do, and how to do it in a way that was consistent with Biggby’s hard-won cultural gains and its not-quite-one-year-old purpose. At the time of the previous layoffs, no one had known, for example, whether a departing person had just bought a home or had a baby on the way. But due to the culture work the corporate office had been doing, everyone knew a lot about everyone else. That made the decision to lay anyone off exponentially harder.

After a series of tortured conversations, the leadership team determined that each of the departing employees would be thanked for their contribution with a payout of any unused vacation time, plus a week of pay for each year they had been with the company. They also decided to share the decision with the entire company at the same time, creating an opportunity for people to ask questions and understand what had happened and why, share the sadness of the moment, and together decide what to do to prevent layoffs in the future.

As the directors explained all of this in the big room, reactions were mixed. One or two people ventured comments like, “My mom was laid off last month and all she got was a margarita from her coworkers. Her managers didn’t care.” There was also a conversation about how everyone had known that Biggby was lagging in its performance, and because of all the talk about supporting people in building a life they love, no one had wanted to hold anyone else accountable for underperformance. But it became clear in the room that looking the other way is not the same as really supporting people.

Looking the other way is not the same as really supporting people.

Despite some appreciation for the learning moment and the care the leadership team had shown, damage was done. For many, the layoffs had shattered a sense of safety and dramatically reduced their trust in leadership. Some found fresh evidence for an assertion that Biggby was not supporting them in building a life they loved. One of the directors took it upon herself to walk one of her departing employees out to her car. Before she drove away, the employee turned to the director and asked, “How could you do this to me?”

♦

The next week was bitterly cold and Bob spent Monday evening at his house in Douglas, Michigan, while a persistent snow fell outside. The smell of garlic and tomatoes filled the air while Bob arranged place settings on the table: one for him, one for his wife, who was singing to herself as she cooked, one for his stepson, home from college for winter break, and one for his mother.

After his all-in moment the previous winter, Bob made very intentional efforts to build relationships with his family. He had finally taken that vacation with his father, and recently he had invited his mother to move to Michigan, into a house less than two miles from his. Now she joins Bob and his family for dinner regularly.

The next morning, Bob drove through the snow back to the office. One big item had been left undone during the purpose process the year before, and the leadership team had given itself until the end of 2017 to complete it: articulating a new vision for the company. They’d been debating the vision in open meetings for the previous three months, and with the year quickly drawing to a close, the pressure was on.

A vision would need to answer the question “What will we achieve by when?” With a purpose as subjective as “Support people in building a life they love,” at first it was difficult to find a good approach to the question, let alone an answer. How would Biggby expand its impact? Offer Life You Love training to customers who came in for a cup of coffee? That seemed cultish. Open a training center and sell courses to people? That was a different business altogether. Further, how would the world change if Biggby was successful? Could the company measure reductions in homelessness, poverty, crime, depression, and suicide? Bob felt at times like the process was going around in circles or veering out of control entirely.

At some point, someone had suggested that the purpose could behave like a ripple effect. If Biggby created a culture that effectively supported people in building a life they loved, word would get out, and other business leaders would want to see what Biggby was doing. Then someone else pointed out that this ripple wouldn’t work unless Biggby was also growing at an impressive rate. Not only was lackluster growth an obstacle to incubating the Life You Love culture within Biggby itself — the recent layoffs made that clear — but it wasn’t a very good sales tool for the concept, either. If another company leader, who didn’t yet grasp the importance of a caring culture or a strong purpose, had a higher rate of growth than Biggby, the case for change was weakened.

So to scale its purpose, Biggby would have to build a culture that reliably delivered both exemplary human and financial results. The team started calling this the Biggby Effect. With the intellectual framework in place, all that was left to do was to determine the specific numbers. The human side came first: “by December 31, 2028, 90 percent of people who have been working for Biggby Coffee for at least a year will have a positive personal score on the Life You Love self-assessment.” Biggby would roll the purpose out to the entire franchise system over the next four years and begin measuring the extent to which people love their lives (as defined by the criteria they had established the prior year). They would tweak their training and development protocols and other internal systems until they achieved the goal.

Biggby Coffee has long-term plans to help all employees, including its baristas, live a life they love.

But the leadership team entered its final meeting of the year not yet aligned on a growth goal that was both sufficiently ambitious to power the Biggby Effect and even remotely realistic. The pain from the layoffs the previous week demanded a kind of rigor and passionate debate the team had not seen before. The meeting almost ended several times as people fought both frustration and flagging mental energy.

As the clock wound down and the team faced the real possibility that they would fail to keep their word to finish the process that year, the tone of the meeting shifted. Someone made a call to reach for greatness, not because it seemed within reach, but precisely because it didn’t yet. The leaders grounded these sentiments with data on what other franchises had achieved and how fast they had done it. Finally, one of the managers proposed setting the target at crossing $1 billion in gross revenue for all retail cafe sales within 10 years.

Mike couldn’t believe his ears. The truth was, he’d been doing some of his own personal visioning work lately, and so he felt in touch with the power of an ambitious goal. He’d decided he still wanted to own the Red Wings, but now he had another legacy in mind. In thirty years, he would be 76 years old and ready to retire. He’d be in Orlando or Las Vegas because those are the only two cities with venues large enough for the more than 10,000 people who will then attend Biggby Coffee annual franchise meetings. Mike would make a final presentation and the room would give him a steady and sustained standing ovation because it would be filled with thousands of people who credit Biggby with supporting them in building a life they love. Mike would walk out of that room and into retirement knowing that it had all been worth it.

Back in the big meeting room, he waited silently until several others expressed support for the $1 billion target before enthusiastically adding that he refused to believe that a team this talented wouldn’t be able to figure out how to reach such a goal. They called the vote and the proposal passed.

It was 4:00 p.m. on Thursday, December 14th, 2017, and the meeting stood adjourned. The leadership team was exhausted. But before leaving, they paused to savor the moment. Mike, Bob, and the whole Biggby family read the words projected on the screen in front of them:

“Most people go to work because they have to, not because they want to. They feel that their employer doesn’t care about them beyond the work they do for the company. This heartless workplace environment reduces the quality of life for them, their families, and their communities, contributing to chronic illness, domestic strife, and many of the other tough problems we face.

The workplace needs to change. Biggby can help.

Biggby Coffee exists to support people in building a life they love. United behind this purpose, our Baristas, Owner/Operators, and Home Office employees will create a culture that empowers us all to intentionally build a life we love. That culture will reach beyond Biggby Nation to our families, friends, and communities.

As Biggby Nation grows, this impact expands. The world will take notice, and the workplace will begin to change.

To achieve this, we must grow, and we must lead by example. By 2028, Biggby Coffee will be a billion-dollar company, and its Home Office employees, Owner/Operators, and Baristas will all be building a life they love.

The workplace will change. It all starts with Biggby.”

Reading the vision was humbling. Mike especially felt aware that Biggby was still in the middle of its own transformation; that there would be no point at which the company would become fully “conscious.” But he also believed that if they were loyal to the journey, always seeking to do the best they could today and learning to do even better tomorrow, then they were making a path for others to follow. The journey hadn’t been and wouldn’t be smooth or easy, and in fact it might be much harder than not starting the journey at all — but he had no doubt it was the right choice.

Biggby Coffee had found its purpose. Now the real work could begin.