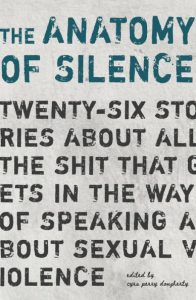

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from “The Anatomy of Silence,” an anthology of non-fiction and creative narratives about the silence that surrounds sexual violence. Reprinted with permission.

“At a time when Black males are losing ground on all fronts, and in many cases losing their lives, rather than creating a politics of resistance, many Black males are simply acquiescing, playing the role of sexual minstrel. Exploiting mainstream racialized sexist stereotypes, they go along to get along, feeling no rage that they must play the part of rapist or hypersexual stud to gain visibility.” — bell hooks*

Perhaps, I’ve acquiesced. Nah, let’s be honest. I have played the hypersexual stud. Usually, I would say something like, “I’m not perfect.” Though it has a Captain Obvious ring to it, my use of the phrase has conveniently served as a feeble attempt at providing cover from accountability. By giving the pre-emptive “I’m not perfect” sing-song, I hoped to silence critics, myself included.

This strategy is used for the not-so-great things: if I’m running late, forgot to send an email, wasn’t transparent in my intentions. “I’m not perfect” is a defense mechanism when I failed to be deliberate. To be deliberate is to take responsibility for my actions — to be accountable. Accountability is scary — that may be the reason why this convenient phrase is so utilized. And yes, I remain scared of what accountability will dredge up. Stakes are high and the consequences can be steep. “I’m not perfect” has, regrettably, been an underlying theme in much of my sexual dealings with women.

#MeToo makes way for reflection

“The Anatomy of Silence” is a collection of creative narratives about the silence that surrounds sexual violence.

In the wake of the #MeToo stories flooding most of our social media timelines, I had a moment that I imagine most other straight, cisgender men experienced. Nervousness. Reluctance to engage. Apprehension. Steady streams of reactive thoughts rattling off simultaneously. Will someone tag me in one of their #MeToo posts? Will someone say I overstepped or violated their boundaries? I had empathy and was uncertain about what would be said. My knee-jerk response morphed into self-preservation, taking deep breaths, hoping nobody said anything. Maybe an ex-girlfriend would describe my roll-over-loving strategy, which included sweet-talking clichés that now sound to me more like coercion than seeking enthusiastic consent. Maybe someone would come forward to say I didn’t pick up on non-verbal cues before, during, and/or after sex. I thought of a couple incidents that I had already sought atonement for but that I still internally battled with my conscience to actually change my actions. #MeToo would potentially be a public reckoning.

The #MeToo movement also had me thinking about the power of stories, whose voices have currency, and whose voices are often silenced. I saw in some massive way how toxic and harmful behaviors were affecting so many of my friends, partners, and colleagues. I took a moment and made a quick Facebook post, which read:

“Re: #MeToo : I want to say sorry and express my apologies to all who’ve been on the receiving end of my BS. To be clear, my BS has been slut-shaming, body shaming, unwanted advances, and womanizing. I want to acknowledge my wrongdoing when people shared with me their stories of experiencing various degrees of violation and I didn’t listen, or take their stories seriously, or didn’t fully hold the space for them. I am sorry. I am sorry when I cracked rape jokes and gave the benefit of the doubt when I suspected a friend of doing foul stuff behind closed doors. I am sorry. I am sorry for my misogyny and silencing. I am sorry to my mans who I gave misguided advice to when they asked about “how to get women.” I want to apologize to a specific woman from college that I felt at the time should’ve given me more affection/attention because I was a “nice guy’”doing nice things. I do not want to continue this pattern and hope we are working toward creating a new normal — one with healing, consent, and respect at the fore. Peace to all survivors.”

The “nice guy” construct in the #MeToo era

The #MeToo movement has been immense and has inspired more mainstream conversations about toxic masculinity and the social conditioning many boys and men have experienced and embodied. From my vantage point, most of the mainstream conversations stop short of nuance in the realm of toxic masculinity. We highlight the extremes, which, as an unintended consequence, provides cover for those who are engaged in toxic behaviors but are considered “nice guys,” “male feminists,” or “allies.” We readily drag public figures on social media but haven’t reconciled our complicity or reckoned with our actions and inactions. Too often, the “nice guy-bad boy” dichotomy has reigned supreme as the barometer for judging men — as if binaries perfectly encapsulate everyone’s experience. I ask myself: Where do I fall on this scale? And the question remains.

No 360-degree assessment has labelled me a psychopath, and no friend or colleague has called me a “sexist pig” — at least to my knowledge. I don’t count any of the most contemporary villains (Trump, Cosby, Weinstein, R. Kelly) as heroes. However, if I move with full honesty, I return to my use of the “I’m not perfect” cover to compensate for my refusal to grow in my dealings with women. This is complicity at best. At worst, I sided with the nice guy template as window dressing but harbored patriarchal views, which deemed women as commodities or sex objects.

In college, I met a woman; we went on a few dates, and I quickly caught romantic feelings. She wasn’t all that into me, but any attention from her meant everything to me. She asked me to help her with a project. I did. I had a hero complex. Weeks later, she received high praise for the final product. When she told me, I felt like the hero, but something was amiss. I reported all this back to a male friend, and he was annoyed on my behalf. That woman was at least supposed to give me some (translation: sex), he said. I didn’t find the concept disgusting or preposterous. I thought he was spot-on. I was not going to approach her with that compensation arrangement. Let it happen it organically, I thought. It never happened. Instead, I stewed in resentment — the same resentment that had been boiling within me from my previous unrequited love days of high school. That couldn’t be me. I was a nice guy. Plus, I had just finished reading “No Disrespect from Sista Souljah.” But nice guys don’t have that kind of entitlement.

More than a decade removed from college, I think differently about the ‘nice guy’ construct. What distinguishes the nice guys from the bad boys may just be performance without substance. The performance of the nice guy (or male feminist) construct could include my use of charm school etiquette and Audre Lorde quotes. The nice guys — deep in their performance — need to be told and reminded that being nice or caring does not warrant access to anyone’s body. No one owes me sex because I made a supposedly heart-warming gesture. Society preaches and punishes the bad boys but assumes the best of the nice guy. And in the quiet, the nice guy is potentially violating people and using his reputation to shield himself from accountability. This pattern silences his survivors.

“Good enough” is not enough

stephen hicks*, author of this essay in “The Anatomy of Silence.”

If you knew better, you’d do better. Maybe, but I knew the standard was low, and I surfed above that bar, knowing I would not be held accountable. Little did I know that bar was so low that, in fact, I would be held in very high esteem within predominantly women, femme, and LGBTQ spaces.

I imagine I’ve been considered “good enough” to sit at their lunch tables or “the best of the worst” in terms of my cis, straight, maleness. Picture me as the overachieving nice guy. I didn’t use the canon of derogatory terms for women or LGBTQ people. I didn’t crack rape jokes or laugh out loud when I heard them. I spoke of advocating for transgender women. I name-dropped Fannie Lou Hamer or Marsha P. Johnson when convenient. I spoke of intersectionality and practiced amplification during staff meetings, which would look like me reiterating what one of my female colleagues’ statements and giving them credit for their idea suggestion.

I sidelined my Wall Street corporate pursuits for social justice and public health work. As my career ascended, I found myself in more spaces where I was the anomaly: the cool, straight, cis, Black guy with muscles, a beard, and a master’s degree. Grandstanding and performing were my key go-to moves. And being in those spaces long enough, I eased into behaviors and practices that did not fully recognize people (specifically women) as more than conduits of my pleasure. It wasn’t benevolent patriarchy; it was more like a woke misogynist with great polish. A nice guy engaging in the same toxicity as his supposed evil contemporaries but with a softer charm.

From performance to accountability

#MeToo has named many, but not all, culprits. #MeToo has me thinking of all of the violations perpetuated by the nice guys — the social justice guys who cite Rebecca Solnit in one breath and who actively silence and control people in the next. Me.

I hurt lots of people on the way here to 32 years old. I diminished people’s feelings and prioritized detachment. Using the colloquialism, I thought with my other head. I used women for my pleasures and maintained imbalanced relationships with them. I was sex-positive without fully recognizing/affirming/celebrating the people I was having sex with.

I quietly rationalized my sexual pursuits as making up for lost time. I was a late bloomer. My schoolmates in middle and high school and college held hands, made out by the lockers, planned mall adventures, talked on the phones for hours, met parents, took prom photos, experimented with sex, and covered all the bases. Not me. I sat lonesome. Never, not once, did I experience that intimate connection with someone else throughout high school and college. Secretly, I was building a wall of resentment toward women, brick by brick. I said to myself, “Once I get the ladies, I ain’t slowing down.”

During my college years, I wished for what some would deem “the good kind of problems” — those rooted mostly in excess. I wanted to be saying ‘no’ to multitudes of women interested in me. And in a whisk of years, I crossed the attractive threshold, and people reacted a bit differently to me — fewer women flaked out on dates; fewer women gave me fake phone numbers; more women inquired about my evening and weekend plans. My time had come. I began doing my thing, all with little regard. This was a time when a friend called me “a walking dick.”

I was 25 years old, and had a few things going for me. I saw women as sexual conquests to be recorded in my files. I made very little effort to transform my perception of women into a full engagement of who they were, complete with thoughts, opinions, beliefs, and experiences. Nah, that was too much. What mattered most was my presentation and sealing the deal — bonus points if neither party gained emotional attachment. I placed more energy in my sexual performance than in fostering intimacy. It worked best (for me) if we kept things transactional. My performance superseded my substance.

I strengthened a skillset through these transactional dealings with women — a polished approach, a detachment. I used sex as a mechanism to validate my worth. I relied on sex to substitute for meaningful interpersonal connections.

I wallowed in guilt in the months preceding #MeToo’s peak. In the evening hours of Friday, November 11, 2016, I finally did something. In an attempt to strike reconciliation or some semblance of it, I reached out to almost all of the women I could think of who were often treated like a booty call or a jump-off only to boost my fragile ego. I sat in a dimly-lit basement apartment thumbing away text messages. I must have texted 30 women that night — women who trusted me enough with physical intimacy and to whom I responded with coy tactics, lackluster affection, and conversation about everything except my feelings and intentions. I imagined this communication mode would be more conducive for naming my misdeeds and not expecting an immediate response.

I do not want to send those types of text messages again. The hurt doesn’t need to continue to a new group of women. I travel with my regrets and remorse, for it didn’t have to be this way. I’m keenly aware when author carmen Maria Machado writes, “How easily we accept women’s pain as collateral damage in men’s self-discovery.” Several women were on the receiving end of my unresolved traumas, and I didn’t do them any favors in extending my toxicity.

Within the last year, I joined a group of people deliberately addressing toxic masculinity in Washington, D.C. They have a program aimed at equipping masculine-identifying persons with tools for emotional labor, consent, and bystander intervention. The program isn’t a magic pill; however, for me, they planted some seeds in fertile soil. I began to unpack the motivations behind being so reckless in my dealings with women. I began to recognize the toxicity of my actions within the context of masculinity. Within that space, I finally aired how I used sex as a tool to validate my self-worth, so I would not have to exert more of myself. I could hide behind a false self instead of bringing my authentic self to my relationships with women.

Writing this essay while knowing my past feels bizarre. This may be my imposter syndrome once again. Thinking back to those behaviors that led to that November night of text messages, I want to honor those women and not lead more men astray.

We know there are many forms of performance — be it through gender, sexuality, self-promotion, or anything else. To be ‘cool’ or ‘woke’ is performative as well. I’m exhausted of performing — namely, I’m exhausted of grandstanding as the nice guy who uses the mask of his perceived distance from toxic masculinity, patriarchy, and rape culture to avoid doing any personal work.

Yes, I have strong opinions about what’s going on in the world. Yes, I think we can harness healthier masculinities. Yes, I can make a change, but I want to do it from an authentic space. I want to be less concerned with convincing women that I’m a good catch. Performative wokeness, I’ve learned, has a hey-look-at-me quality. More emphasis is placed on receiving brownie points than actually making a point. The sure-fire way for me to gauge if I am performing is based on my willingness to be in meaningful connection: Am I aiming to connect with these people or show them that I am a good person?

My text messages were meant to remove the sheen and move myself toward accountability. I want to make space for those who have been silenced to express themselves. I have to be careful because I recognize even my accountability-seeking efforts could become performative. It’s not meant to be an act coming from a self-serving, oblivious space. I am trying my best to translate my thoughts and feelings into meaningful change. I now know that there will be some sort of reckoning for my actions — good, bad, or without description. My actions have to speak louder than my words. In doing so, I am actively self-defining, healing, and resisting — not merely acquiescing.

“The Anatomy of Silence” is an anthology of non-fiction and creative narratives about the silence that surrounds sexual violence. The book presents unflinching analysis by 26 survivors and allies talking out loud (often for the first time) about what it means to stay silent, to be silenced, to be complicit in silencing others. Get your copy here.

*both bell hooks and stephen hicks use all lowercase letters for their names — this is a form of protest against the previous generations of slave owners from whom their names descend.