A Brief Timeline

Rumors tend to abound when it comes to the folklore espoused by advocates of Prohibition, and by many of those who claim to be friends and protectors of the plant cannabis sativa. As with any history, understanding the complexity of cannabis’s path through the law is a great way to understand its current status — and stigma — in the popular imagination and in the business community. With that said, being armed with objective facts about the ways cannabis is being radically commoditized in a legal market, and the way the industry is rapidly evolving, is likely the best way to assess your relationship to this plant, and whether and how that relationship is likely to blossom into a business.

To begin, imagine the 1850s, when medicinal preparations of cannabis were sold in American pharmacies (think tinctures). At this point, “hemp preparations” and “cannabis preparations” were terms used interchangeably on vials. Now imagine the 1880s, when at least 500 “parlors” existed amongst the hippest American cities and cannabis was used “recreationally” by an entire cross-section of consumers. And yet, by the early 1900s, the bulk of cannabis activity was seen through the consumption of “marihuana cigarettes” enjoyed by Mexican laborers who had emigrated to the US during the Mexican Revolution, and through the jazz scene that was emerging in cities across the country, which was largely associated with an artistic Black community that already posed an existential threat to established White culture.

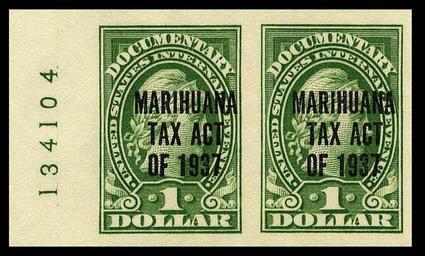

In 1906, concerns had been raised as to the loose labeling regulations that existed pertaining to cannabis. In order to address this, the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed by Congress, requiring that certain “drugs,” including cannabis, be accurately labeled, prohibiting adulterated products from entering the stream of commerce. By that time, numerous states, including Iowa, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Arkansas, Nebraska, Louisiana, and Colorado, had passed laws regulating marijuana as a “poison.” Thirty more states had anti-cannabis policies (various iterations of poison laws) on their books by 1933 — which, ironically enough, was the year alcohol prohibition was repealed. And in 1934, the Uniform State Narcotic Drug Act was enacted in order to help the US carry out its obligations under the Hague Convention of 1907, attempting to make laws uniform across the country restricting the sale and distribution of narcotics. This ushered in a host of state-specific laws that attempted to regulate the sale of cannabis through pharmacies, requiring the use of physicians to prescribe it. This is also what would pave the way for a Marihuana Tax Act to pass out of Congress in 1937, and for the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act of 1938, which to this day, defines marijuana as a “dangerous drug.”

Marihuana revenue stamp

It wasn’t until President Nixon signed into law the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Act of 1970 that cannabis was actually rendered federally illicit, wherein Title II of the Act contained a schedule of controlled substances, of which cannabis was one. The Act served as implementing legislation for the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, a treaty enacted by the UN in 1961, which expanded the reach of earlier treaties to include cannabis. (Similarly, the Single Convention Treaty has since been supplanted by acts broadening the international scope of illicit substances to include psychotropics, such as LSD and MDMA.) Cannabis becoming scheduled as a controlled substance would imply total prohibition on the possession and sale of cannabis, even for doctors and their patients.

What’s given rise to this web of public policies is instructive because it embodies the duality of our current cannabis complex: propaganda-stirred public sentiment to the extent that over-regulation in the form of Prohibition was made possible. Remember that it was 1936 when the film Reefer Madness was released as a tool of propaganda by the state, and an entire cult of fear was created around the racist effects that rampant cannabis use was projected to have on society as a whole. (Reefer Madness is said to be a “cautionary tale” featuring a fictionalized take on the use of marijuana. In the film, a trio of drug dealers lead innocent teenagers to become addicted to “reefer” cigarettes by holding wild parties with jazz music.) Racism initially, followed by an overt recognition by President Nixon that a War on Drugs would enable the state to lock up those who served to undermine a certain social order — namely, dissidents to the Vietnam War and people of color — would end up building our current prison industrial complex, relying on the mass incarceration of, in particular, young men of color, for the possession of even the smallest quantities of cannabis.

Where We Are Now: Hemp Versus Cannabis

In 2019, we are at an incredible crossroads. The first floodgate moment was the election of 2016. That November, nine states voted on cannabis ballot initiatives. California’s served to legalize adult use (“recreational”) cannabis, as did Nevada’s, Massachusetts’s, and Maine’s, while other states such as Arkansas, Montana, North Dakota, and Florida all legalized medical cannabis. This was a big deal. While many of us in the industry felt a palpable fear as to the direction our country might soon be headed in politically, we also recognized that the tipping point for our issue had been reached. We would continue to have to fight for access to banking, tax parity, intellectual-property protection, and a host of other structural issues, but we were winning the will of the American people and not just when they “liked” pot stories on Twitter or Facebook. People took to the polls, and they approved legalization in blue and red states alike.

Since those ballot initiatives passed, and as we begin to see states like Vermont, Connecticut, and New Jersey force this issue through their legislatures, there has been another monumental event that’s helped light up the cannabis space — that, of course, is the Farm Bill of 2018 (also known as the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018). While many readers of Conscious Company are familiar with the Farm Bill because of its applicability to a whole range of issues tied to agriculture, readers may not be as familiar with the section of this past year’s Farm Bill that removed hemp from the Controlled Substances List, rendering not just industrial hemp legal (as it was rendered in the 2014 Farm Bill under President Obama) but by implication, hemp-based CBD (CBD is a compound in cannabis that is believed to have limited if any psychotropic effect), of which a derivative was approved by the FDA earlier in 2018.

This means that currently, hemp-derived products are enjoying a legal status they’ve never had before. How are we defining hemp? Well, for that definition we go back to the Farm Bill of 2014, which states that hemp plants are cannabis plants containing .3 percent or less THC. That hemp is only regarded as legal, though, if its growth is registered with a state office that presides over hemp cultivation licenses. Although, to make matters even more complicated, in contradiction to official guidance from the FDA and DEA in 2016, when it was clarified in that year’s Farm Bill that the creation of a legal path for hemp production does not mean that product can pass back and forth across state lines, the United States Department of Agriculture just announced at the end of May 2019 that, regardless of whether hemp is a registered crop in whatever state it is grown, interstate commerce is not prohibited. Justification for this is ultimately its de-scheduling via the 2018 Farm Bill, but the decision comes in lieu of regulations being enacted by any state agency and is a clear signal that hemp and hemp-based CBD are on the verge of becoming a truly national market (as opposed to being ring-fenced from state to state).

It is also extremely important to realize that when you are looking at a CBD-only product, you are looking at an isolate that came from a plant that could have started out with a THC potency profile of more than .3 percent or a plant that started out with that little or less. In the first scenario, you are looking at an isolate of cannabis, and the only way for that plant matter to have entered the market lawfully is if it was cultivated under a marijuana business license issued by a state that has legalized “full-spectrum” cannabis (also known as marijuana). In the second scenario, you are looking at a hemp-based CBD product that may or may not be legal for the manufacturer or retailer to sell. You will not be prosecuted for possessing it, but depending on the state, whoever sold it to you could be. Prosecuted for what, you ask? That is also a difficult question to answer. Just this past year, the US Postal Service issued an advisory notice about its own policies, anticipating that its rules will soon be revised such that if a hemp producer is shipping products in line with the hemp rules of its state, that its transfer across state lines using the federal mail service will not be deemed illegal. And while no FDA regulations concerning hemp or CBD have been issued yet, a hearing took place at the end of May specifically so that the FDA could hear testimony related to CBD regulation. This is significant because, despite the current absence of clear regulations, many CBD distributors have received cease-and-desist letters from the FDA due to medical claims they’ve made about their products through their labels, websites, etc.

In contrast, cannabis that is marijuana — plants that contain more than .3 percent THC — is treated by the law quite differently. There are very strict regulations in place, from the requirements businesses must meet to become licensed to the requirement that these businesses be licensed at all, to the lab testing that product must meet and restrictions on advertising. And because licensing and other components of marijuana-licensing regimes are so comprehensive, it’s essential to understanding these pieces if investors or entrepreneurs are to sensibly approach this market.

Licensing Regimes and Social Justice

Post-repeal of the 18th Amendment in 1933, states were faced with a similar conundrum to what they are currently facing concerning pot. While we have not gotten to the point of federal prohibition simply dropping, we have been chipping away at it through the issuance of guidance documents such as the Cole Memorandum and FinCen Guidelines that have been in effect since 2014. Cannabis companies are now listed on both the NASDAQ and NYSE in addition to the Toronto Stock Exchange, and Congress remains barred from using federal funds to enforce the Controlled Substances Act in states where violators are acting lawfully under their state’s laws. And yet, similar to the establishment of dry counties in the wake of Prohibition’s abolition, municipalities frequently rail against the legality of cannabis and ban commercial activity related to it. California is rife with this issue, as citizens continue to battle over both access to the plant for personal use and for access to the plant for commercial purposes.

Many in California attest to the desire to conduct businesses in a fair fashion, with access to and education about cannabis as a therapeutic plant and not just another legal commodity to be traded on and profited from. But entrepreneurs throughout the state are struggling. The difficulties inherent in becoming a licensed player in the cannabis space are myriad, first from a state-level compliance perspective, then from the standpoint of needing to obtain all relevant local licensing, encompassing the typical paperwork involved for any business to get started compounded by the ever-evolving regulatory schemas that towns and cities are pioneering for the first time. Moratoriums on commercial activity are common, as is backlog in application processing and fundamental changes in policy enacted after application fees have been paid and substantial work has begun on cannabis-related projects.

The challenges that Californians in the cannabis space face is unique because of the sheer scale of California’s economy and the relative impact that any changes in economics around a particular commodity can have. An enormous sector of employment in California has been disrupted by legalization, and environmental controls are being implemented that impact how generations of farmers have chosen to cultivate their cannabis. It is arguable that the financial health of communities across the state, from urban to rural environments, has been de-stabilized through the advent of legalized adult use regulations. And key to this is licensing.

Similar in the alcohol industry, licensing is what allows businesses to not just shore up market share but to be compliant, the significance of which cannot be overstated in the cannabis industry. Pot entrepreneurs, perhaps more than any other type of businessperson, are concerned with compliance. That is because without perfect compliance, there is no shield from federal enforcement of draconian drug policies that can easily result in civil asset forfeiture and incarceration.

In terms of investing, licensing is also imperative. The first matter of due diligence when you are vetting a cannabis-related opportunity is to assess whether the activity engaged in is one that should be licensed in whatever state that activity is taking place. For instance, cultivating cannabis for commercial purposes (more than a home-grow of six plants) will always require a license, even if it’s what that state considers a “microbusiness.” Manufacturing will always require a license, as well (for instance, turning marijuana buds into chocolate). And dispensing (retail) will always require a license. It is an open question though, from state jurisdiction to state jurisdiction, whether things like delivery or distribution are “transportation.” In many states, analytical labs in the cannabis space have a licensing type. Not so, though, in states like New Jersey, where the industry is statutorily required to rely on a state-run lab for the purpose of testing product for potency and toxicity. That’s the state-level licensing regime in a nutshell.

Local licensing gets interesting because in many states, municipalities can decide for themselves which vertical markets they want or don’t want within their limits. Lab testing could be allowed, for instance, but not cultivation or retail. Zoning issues become stumbling blocks frequently, as setback requirements in particular can severely limit the real estate options available for marijuana businesses. Being relegated to various areas of a city can present constitutional issues as well, which are difficult to fight because of the view that cannabis business licenses are a privilege, not a right — although the underlying issue here is also a constitutional one: the rights of patients to have access to cannabis within reasonable reach.

Complicating matters even more is the entrance of large cannabis companies whose business models (and valuations) depend on the acquisition of licenses and the ability to justify incredibly high projections of revenue based on these licenses’ hypothetical value rather than on the actual value of the product those licenses and their operations generate, or from the standpoint of a consumer, or a member of the community where that large cannabis company’s holdings physically exist. In California, a removal of acreage caps in the final version of the regulations implementing the act that combined legalization measures for medical and adult use (commonly known as MAUCRSA) produced ideal conditions for licenses to be layered on one another in such a way that massive farms are currently some of the only fully legally operating entities with product on the market in California.

Merit and Equity

There are a couple of other major pieces to consider when you’re trying to understand how the cannabis industry works, specifically in terms of licensing and the hope for a cannabis industry we can feel good about. For one, many states utilize a merit-based application system, whereby applicants are competing with others in their geographic area for a limited number of licenses.

The particularities of applications differ from state to state, but ultimately, the gamut of what must be provided runs from a description and background check of an operation’s team, a business plan with clear sources of funds and capital formation strategies identified, operations policies and procedures related to everything from the growing and processing of cannabis to the security plans that will be used, a network of community partners to account for all aspects of the supply chain, to software used for financial accounting and to establish and preserve chain of custody. In competitive jurisdictions, it is not just a matter of checking off boxes, it’s a matter of being able to provide a narrative that describes what you are doing as a cannabis business and how you will deliver on what you are offering the jurisdiction that gets applicants points. Some jurisdictions even go so far as to require community engagement plans, and points for addressing diversity as a component of ownership not just hiring, are also awarded (Pennsylvania’s medical market is a great example of this).

Going further, some states are setting aside permits for equity applicants, such as Maryland, where a social equity application process is being conducted separately from general permitting. States can create set-aside budgets for such programs, as is being contemplated in New Jersey and has been initiated in cities like California’s Oakland and Los Angeles. Social equity advocates are pushing hard in states like New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut as well, insisting that the expungement of drug-related offenses for those who have been convicted of activity that is now forming the basis of a legal market must be part and parcel to any enabling legislation that would create a licensing path for behavior that some citizens remain locked up for. Massachusetts has gone so far as to be discussing exclusivity on delivery licenses for those who would qualify for equity permitting for the first two years that this license type exists. The intention is to provide those who have been hardest hit by the War on Drugs with meaningful ways by which to enter a legal market and have a chance to gain a foothold in the industry through the establishment of fully capitalized infrastructure and brand development.

Takeaways

There is an enormous amount of ground to cover in a 101 on Cannabis, especially cannabis from a conscious perspective. We haven’t even gotten to dig into the scientific research that is available, the research that is coming, and the laws we need to change in order for that to happen. We haven’t gotten to the intellectual-property questions that research and development questions raise, from a brand development, consumer-facing perspective and from a more macro perspective than that: how do we want strain technology to be owned? How can restrictions on seed-sharing as a practice of generational farming be guarded against? How are lab-testing requirements being enacted from state to state? How are they being enforced? What kinds of research partnerships are possible between operators and universities? How can community development and cooperative models be effectively driven by legislation? How do we understand market differentiation from cannabinoid to cannabinoid (e.g. THC vs. CBD vs. CBDV)? How are issues like the risk of impaired driving and employee drug testing being navigated? Ultimately, how do we approach these questions mindfully from a public-policy standpoint? And how can the growth of discourse around these issues related to cannabis be pursued from a holistic perspective?

The takeaways here involve realizing that in any industry, there is a tension between the purely financial interests of a company and its interests overall, in terms of its long-term sustainability. What is good for the masses is often good for a company, while putting the good of society at the heart of a business model is what is revolutionary and counter to the traditional capitalist model. In essence, occupying this space of tension and addressing the issue of social impact as a factor in measuring sustainability is what makes a conscious company. And yet, profitability at scale with net-positive social impact is a challenging imperative, even in industries that do not face the constraints that cannabis businesses face .

There are two major ways the Conscious Company community can support and take action within the context of the cannabis industry. One is by lending its ability to lead and make business decisions in a way that skillfully blends the priorities of profit, people, and planet to create machines that build wealth and wellbeing. It may be a turbulent environment, but never have you come across an industry with so much passion for the concept of liberation and reverence for plants and all that the plant world has to offer. The industry needs role models, though. It needs successful entrepreneurs and social impact investors who have experience making values-based businesses profitable and pushing for legislation that enables this approach to conscious commerce, conscious capitalism, and conscious business. What the industry has to offer in return is limitless if entrepreneurs are able to find and build with this type of support.

This article is intended as a jumping-off point for the Conscious Company community to begin talking about cannabis (full-spectrum and cannabinoids such as CBD) as an opportunity for values-based business in this country and abroad to flourish. Please leave a comment or contact Shoshanna@pistilandstigma.com directly with any questions about what you’ve read or requests for us to cover specific issues in future posts.