Scaling social and environmental innovation (collectively “social innovation” for this article) requires an atypical perspective compared to traditional startup frameworks. Here we propose a new framework using the analogy of climbing a ladder to aid social entrepreneurs and funders in evaluating new opportunities for scale and developing strategies to achieve scale.

A common problem in the social innovation ecosystem is the challenge of scaling. This is the result of many factors, including several issues that are unique to social innovation enterprises. However, for an entrepreneur starting a new social enterprise, the resources used to guide startup efforts are often insufficient in that they fail to holistically address the complexities that surround scaling social innovation.

In order to create the change the world needs at the pace and scale needed, the power of market-driven scale is a crucial component to success. Unfortunately, social entrepreneurs face significant hurdles in achieving market-driven scale, often driven by challenges in the external environment where the enterprise operates. Market activity may be distorted by governments or aid agencies. Political rules and/or cultural norms may limit market growth, and infrastructure may be lacking for distribution or information sharing. Even if a market is present, it may still be nascent in its development — and yet pathways remain for the development of market-oriented, scalable solutions.

Despite these challenges, social entrepreneurs can still build plans for long-term, market-oriented, independently sustainable business models. They simply need the proper tools and resources to better understand the unique challenges they will face. These resources, combined with suggestions for the strategic deployment of those resources, will be better equip entrepreneurs to direct their efforts toward developing a successful business model. Without that understanding, innovations struggle to scale and funders struggle to understand how to support them. They become “social service ventures”:

“These…ventures never break out of their limited frame: Their impact remains constrained, their service area stays confined to a local population, and their scope is determined by whatever resources they are able to attract. These ventures are inherently vulnerable, which may mean disruption or loss of service to the populations they serve. Millions of such organizations exist around the world — well intended, noble in purpose, and frequently exemplary in execution — but they should not be confused with social entrepreneurship.”

This results in an ecosystem with considerable confusion about which solutions to scale and how to scale them. This confusion (or lack of strategic clarity) prevents both nonprofits and mission-driven for-profits from developing business models and strategies for scale.

Social entrepreneurs who develop targeted local solutions in niche markets may want to scale but struggle to find markets. University researchers often publish papers and move on due to the difficulty in commercializing and scaling their ideas, leaving potentially world-changing ideas to sit on the shelf. Funders provide program-specific grants or donations rather than funding overhead or investing in development of the sectors or systems needed to support scale and greater impact. Underlying it all is a lack of structures or incentives pushing or pulling entrepreneurs and funders into the growth and scale arena.

The future requires social entrepreneurs to pursue large-scale, transformational change through markets. To do this, it is critical to establish a more holistic framework for evaluating market-driven-scale potential with the goal of providing both entrepreneurs and funders more clarity and direction on how (or under what circumstances) to move social impact forward:

“Understanding the means by which an endeavor produces its social benefit and the nature of the social benefit it is targeting enables supporters…to predict the sustainability and extent of those benefits, to anticipate how an organization may need to adapt over time, and to make a more reasoned projection of the potential for an entrepreneurial outcome.”

The following is our proposal for a new, more holistic framework for evaluating readiness for scale and establishing strategies to scale social enterprises. Our framework represents key learnings from our personal experiences in early-stage venture capital and accelerators, sustainability research and innovation, and environmental economics. It also incorporates the aggregation and synthesis of various books, professional and academic research reports, case studies, and other frameworks such as the business model canvas.

While more work and research are needed, we hope the introduction of this framework will bring together participants in the social innovation ecosystem around a common approach to developing business models and strategies to achieve market-driven, transformational scale.

Climbing the Social Innovation Ladder

The current approaches to scaling social innovation are akin to trying to climb a tall wall with a short ladder, set on top of uneven ground without anyone to hold it. At the top of this ladder is the transformational change social entrepreneurs want to achieve, but they lack the necessary and appropriate ladder and support to get there.

To more quickly “scale” the ladder it needs to be placed on a solid foundation, someone needs to hold and stabilize the ladder, and the ladder needs to be extended so that it can reach the top. Hence, we refer to our framework as helping entrepreneurs “climb the social innovation ladder.”

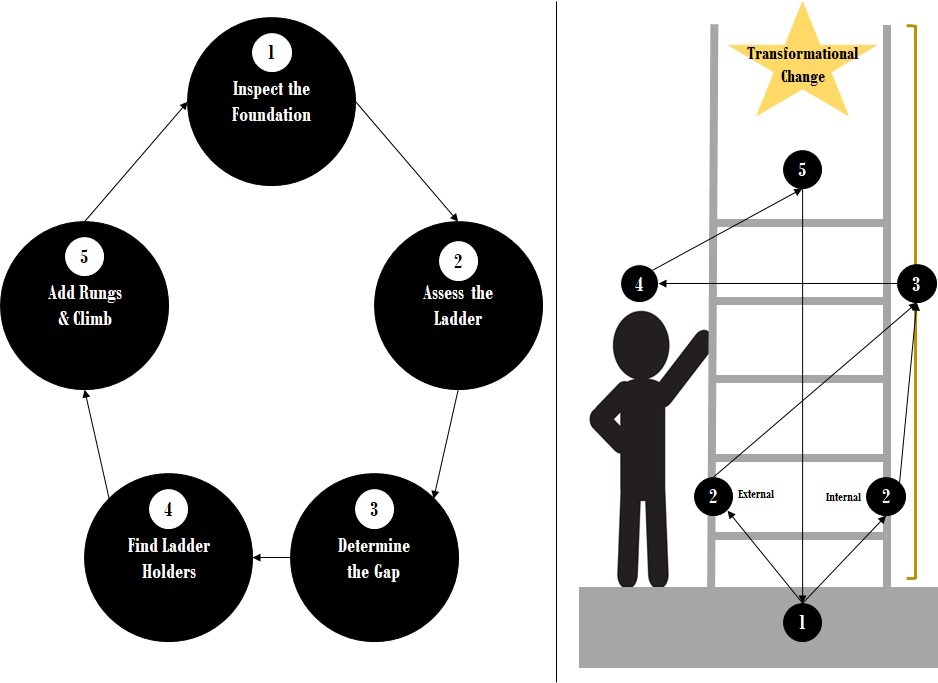

To build this better ladder requires a five-step process that gets repeated over time:

- Inspect the foundation: evaluate the purpose, mission, and vision of the enterprise in the context of the external environment the enterprise is or will be operating within.

- Assess the ladder: assess the internal dynamics of the enterprise’s model and product/service attributes to determine readiness and ease of scalability.

- Determine the gap: establish where the enterprise sits along the continuum of developing the market and its corresponding risk and capital scarcity.

- Find ladder holders: pinpoint potential partners from private, public, and social sectors, particularly channel partners (i.e., sales and distributions channels) and finance partners.

- Extend the ladder and climb: establish milestones, develop strategies that move towards transformational change, and execute (return to step 1 and repeat as needed).

Using this process, we believe innovators and funders alike will be better able to assess an organization’s readiness to scale and more effectively build and implement strategies to achieve scale. Figure 1 visualizes this framework.

Figure 1: Climbing the Social Innovation Ladder

Step 1: Inspect the Foundation.

Evaluate the purpose, mission, and vision of the enterprise in the context of the external environment the enterprise is or will be operating within.

Before climbing the ladder, the foundation on which it is placed needs to be inspected. The goal of step 1 is to evaluate the purpose, mission, and vision (collectively “PMV”) of the enterprise in conjunction with the external environment the enterprise is or will be operating within.

Here, we leverage the “Conscious Capitalism“ (Chapter 3) definition of PMV as follows:

- Purpose refers to the difference the enterprise is trying to make in the world.

- Mission refers to the core strategies that must be undertaken to fulfill the Purpose.

- Vision refers to a broad view of what the world could be once the Purpose is achieved.

This is the underpinning on which a strategy for scale is built. With a clear PMV at the forefront of decision-making leadership teams can make quicker, better, and bolder decisions that ultimately lead to superior performance.

In traditional startups, PMV is inherently aligned to a market scaling strategy. However, in social enterprises this is not always the case. Many organizations develop too narrow a scope for their PMV or are forced into a narrow PMV by funding limitations and expectations. This forces decisions that inhibit the potential for long-term impact.

Moreover, the unique environmental barriers a social enterprise faces are often different from traditional startups. That is why developing a proper PMV must be supported by a thorough understanding of the external operating environment to identify the unique challenges often faced by social enterprises.

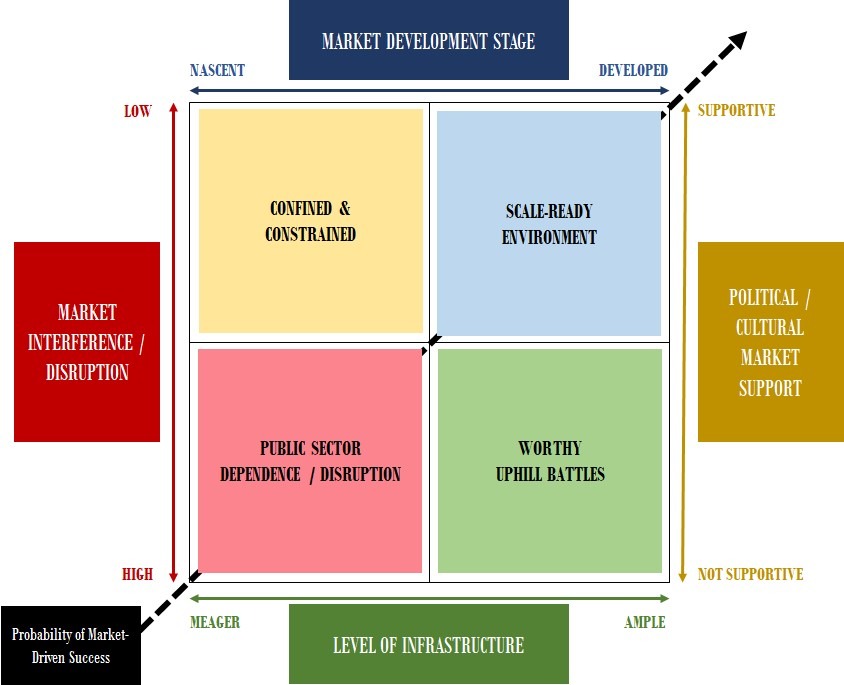

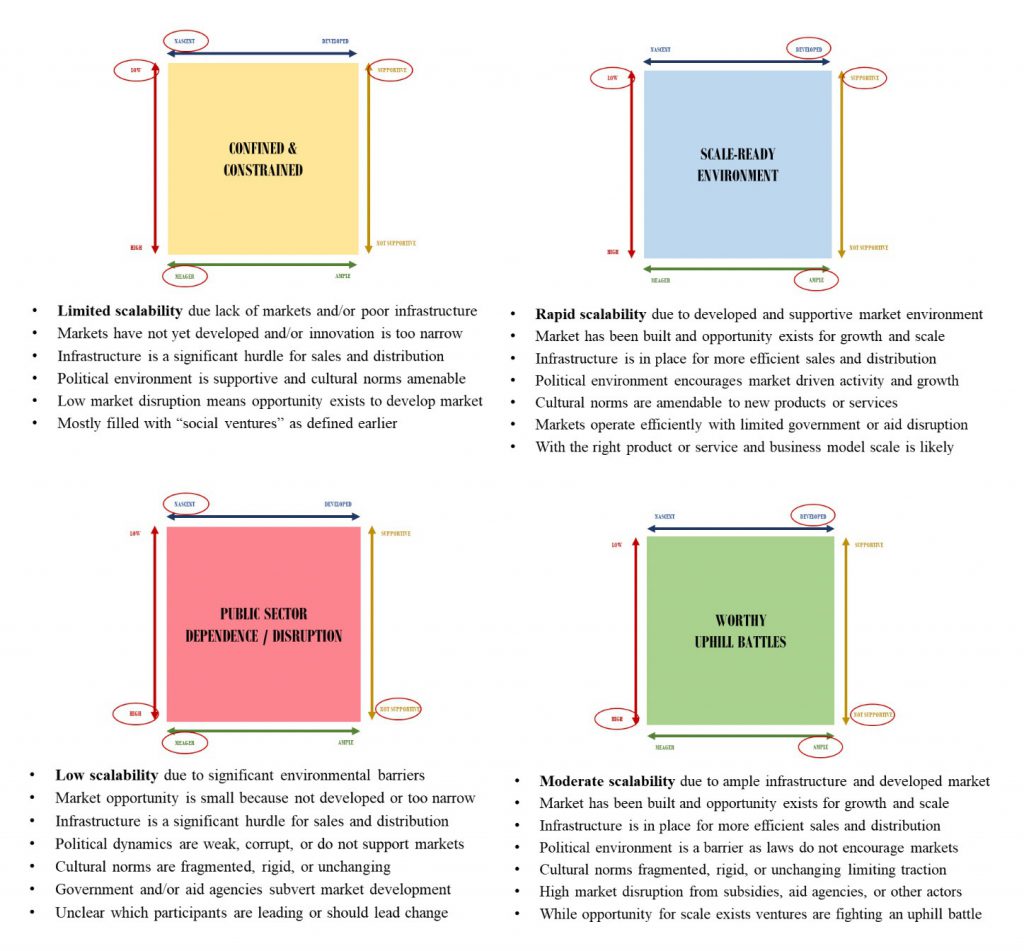

To aid in this process we have developed a tool to help determine whether the external environment is more or less supportive of scale and which challenges an enterprise may face. We call this tool the “Environmental Canvas” (see Figure 2 below). This is presented as a box with each side of the box representing a unique environmental consideration that social enterprises often encounter. These considerations each reflect a range of extremes that are either less or more supportive of market driven scale over time.

The four considerations we present are:

- Market interference/disruption (i.e., government or aid subsidy) ranging from “low” to “high”

- Stage of market development (i.e., robustness of market dynamics and talent availability) ranging from “nascent” to “developed”

- Level of infrastructure (i.e., distribution infrastructure and/or information networks) ranging from “meager” to “ample”

- Political and/or cultural support of market development (i.e., rules and norms that either inhibit or enable robust markets) ranging from “not supportive” to “supportive”

The intersections of these variables result in four separate quadrants, each with its own unique challenges and characteristics (see Figure 3 for an overview of the unique characteristics present in each quadrant). The lower left quadrant is an environment least supportive of market driven scale while the top right quadrant is most supportive of market driven scale.

Figure 2: The Environmental Canvas

To evaluate which quadrant an enterprise may fall into, we have provided several guiding questions below for each variable. Many of these questions were derived from our personal experiences as well as the Strategy section of “Business Model Generation.” Within each variable it is important to consider potential inhibitors or enablers of market-driven scale.

| Variable | Guiding Questions |

| Market development stage | ● How large and how sophisticated is the talent pool? ● What is the ability to attract, hire, retain necessary talent? ● Is there an existing market sector for your product or service? ● What is the general customer willingness and ability to pay? ● Is the macro economy in a boom or bust phase? ● How high is the unemployment rate? ● How would you rate the quality of life? |

| Level of infrastructure | ● How strong is the public infrastructure in your market? ● How easy is it to obtain the resources needed to execute? ● How would you characterize transportation, trade, school quality, and access to suppliers and customers? ● How strong is technology and communication infrastructure? ● How reliable and viable are public services for organizations? |

| Market interference / disruption | ● What level of subsidy exists as it relates to the product/service? ● Which aid agencies or government programs are present in the market that may provide a similar product or service? ● Which incumbent and/or new entrant competitors (if any) are disrupting the market or industry? ● What is the potential for non-market driven product or service substitutes (e.g., from government)? ● How high are individual and corporate taxes? ● What rules may affect your business model? |

| Political / cultural market support | ● Which regulatory trends influence your market? ● What level of political corruption may exist in the market? ● Which regulations and taxes affect demand or ability to sell? ● Which trends might influence customer behavior? ● Which cultural norms could affect your business model? ● Which societal values could affect your business model? ● Identify and describe key societal trends. |

Figure 3: Environmental Canvas Quadrant Characteristics

It is important to note that this environmental assessment is not meant to demonstrate that entrepreneurs should avoid difficult operating environments. Rather, this assessment is meant to force them to think critically about how the environment may impact their ability and strategy to scale, and how this may require them to think different about their PMV.

It is often overlooked, but one of the key changes an enterprise will have to make when deciding to scale an innovation is reframing the problem, and therefore the PMV, of the enterprise. This is essential for determining which strategies they may need to employ in order to effectively navigate the dynamics of each environment as they scale towards transformational change.

Step 2: Assess the Ladder.

Assess the internal dynamics of the enterprise’s model and product/service attributes to determine readiness and ease of scalability.

After inspecting the foundation on which to place the ladder, the ladder itself must be assessed to ensure that it is ready for climbing. This is achieved by evaluating the internal dynamics of the enterprise in order to assess readiness to scale and ease of scaling.

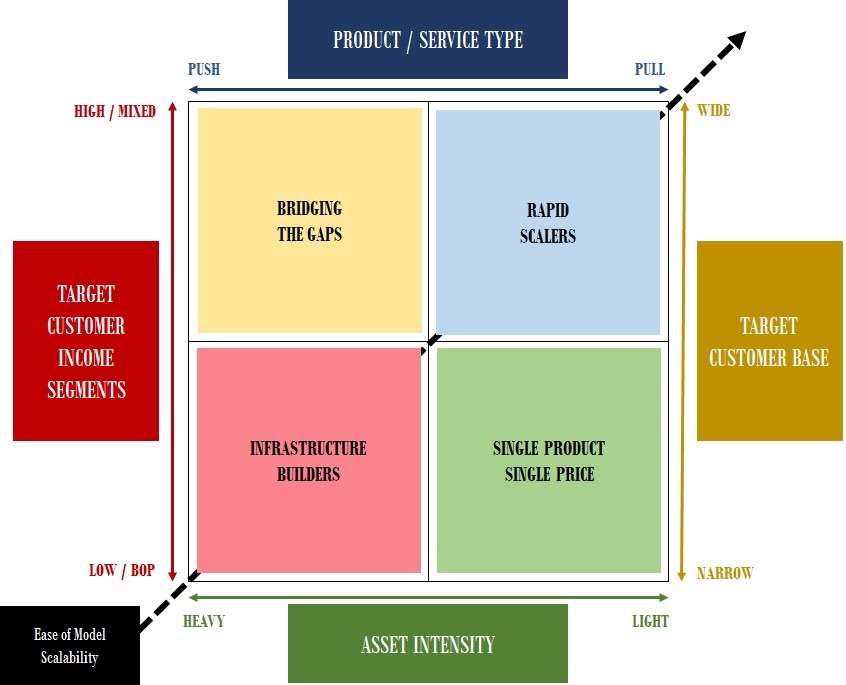

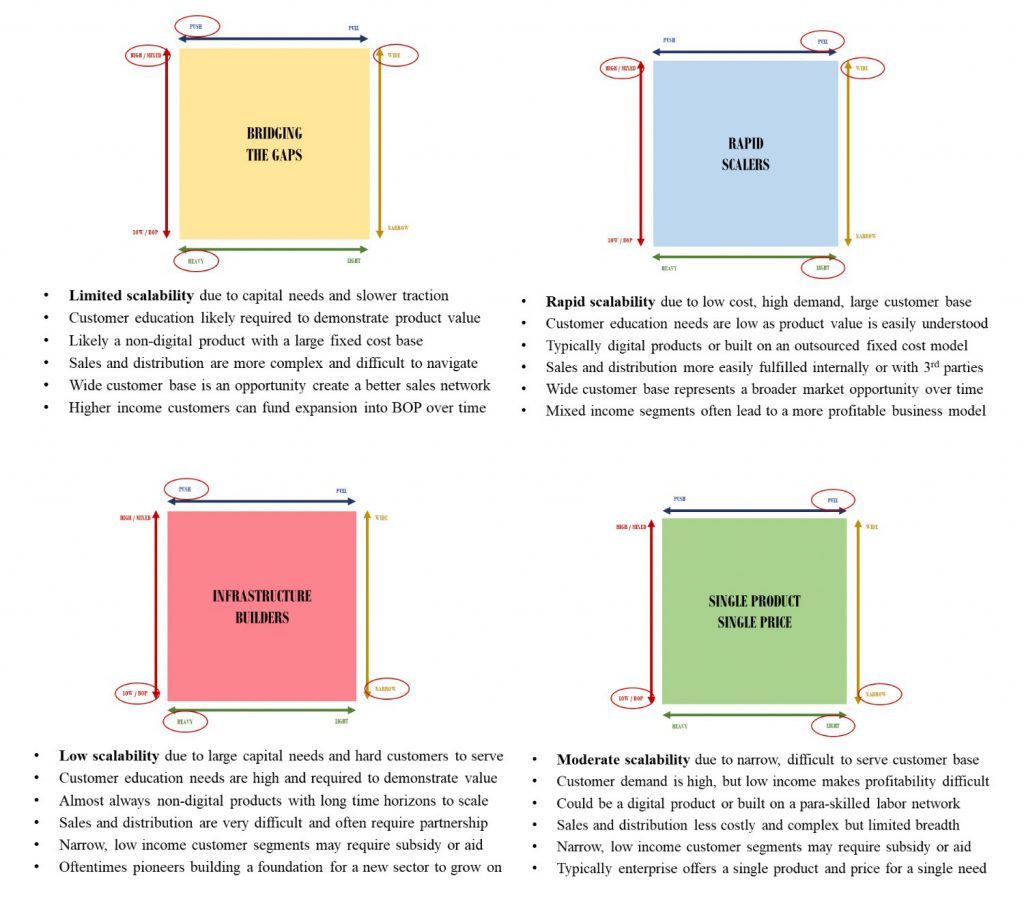

Like the external environment, social enterprises pursuing market driven scale also need to consider the unique characteristics of their solution as they try to balance both impact and financial sustainability. We call the tool to assess the internal product-service attributes the “Product-Service Canvas.” It is a tool similar in function and structure to the Environmental Canvas except the variables assessed now relate to the business model and/or product/service attributes of the enterprise (see Figure 4).

Leveraging this report from Deloitte we look at the following four considerations:

- Product-service type (i.e., a push versus a pull product or service) ranging from “push” to “pull”

- Asset intensity (i.e., a capital intensive versus low cost, flexible model) ranging from “heavy” to “light”

- Target customer income segments (i.e., a higher/mixed income or a lower/base of the pyramid (“BOP”) target market) ranging from “low / BOP” to “high / mixed”

- Size of target customer base (i.e., a wide and broad or narrow and niche customer base) ranging from “narrow” to “wide”

Once again, the intersections of these variables result in four separate quadrants, each with its own unique characteristics (see Figure 5 for an overview of the unique characteristics present in each quadrant). The lower left quadrant is a business model/product/service that may be hardest to scale while the top right quadrant is one that is easiest to scale.

Figure 4: The Product-Service Canvas

To evaluate which quadrant a product or service may fall into, we have provided an overview of the descriptions and definitions for each variable for users to better understand the spectrum of product-service dynamics being assessed. Leveraging the same report from Deloitte we put together the following definitions for each variable.

| Variable | Overview / Definition |

| Product / Service Type | Being a push versus pull product/service depends on the return it provides, adjusted for time and risk. Products with a high return, provided quickly and with little risk (e.g., food) are desired. Products with an uncertain, future return (e.g., insurance) are less desired.

● “Push” = less obvious value or provide uncertain benefits in the future (e.g., health insurance) ● “Pull” = highly valued products with strong, ready demand that can be used immediately with little risk (e.g., food and electricity) |

| Asset Intensity | Asset intensity typically relates to infrastructure, overhead, and distribution costs. There are generally three factors at play:

● “Heavy” = carry a higher cost structure due to the need for physical presence, complex distribution channels, and a skilled labor force (e.g., a manufactured product) ● “Light” = have low marginal costs and up-front capital requirements (e.g., a mobile phone app) |

| Target Customer Income Segments | This relates to the range of income levels served. Some focus on a single, low-income segment, some focus on a higher/middle income segment, and some sell to a range of customers across income levels.

● “Low/BOP” = clearly intended for a single, lower income base, which is often obvious because the enterprise sells products or services that higher-income customers would not buy or need ● “High/Mixed” = serve a wide range of customers, evidenced by different products at different prices that are sold to different income segments based on the purchasing power of the customer |

| Target Customer Base | This relates to the potential to serve a larger or smaller base of customers. Products or services that can appeal to or serve a larger base of customers, regardless of income level, have a much wider audience to reach versus the opposite.

● “Narrow” = oftentimes offering a single product or service at a single price that is relevant to only a particular customer segment ● “Wide” = oftentimes offering multiple products or services at that are undifferentiated between the various income segments served |

Figure 5: Product-Service Canvas Quadrant Characteristics

It is important to note that this internal assessment is not meant to deter entrepreneurs or funders from pursuing asset heavy, push products or services. In fact, we hope that more entrepreneurs and funders address problems that require solutions such as these. These are often the problems and issues most in need of change and can result in significant long-term societal impact:

“…the reality is that much, if not most, critical development work necessarily entails asset-heavy operations, often delivering push products. Most of what development field want to do involves efforts such as providing health and education to populations in urban slums and rural villages…finding solutions for access to clean drinking water, basic sanitation, life-saving vaccines and medicines, safer cooking methods, and so forth. These are all goods and services that must be manufactured or carried long distances, distributed through real property, delivered by skilled and expensive workers, sold via lengthy educational campaigns, and the like.”

Together, steps 1 and 2 help create a more holistic picture of the important challenges, barriers, constraints, and hurdles that the enterprise may need to overcome as it attempts to scale towards transformational change, anchored by a scale supportive PMV. Even if the assessments indicate scale is more difficult, this does not mean those paths should be avoided. Rather, we hope both early and later stage enterprises are encouraged to craft an appropriate business plan and strategy for climbing the ladder regardless of where they begin.

Step 3: Determine the Gap.

Establish where the enterprise sits along the continuum of developing the market and its corresponding risk and capital scarcity.

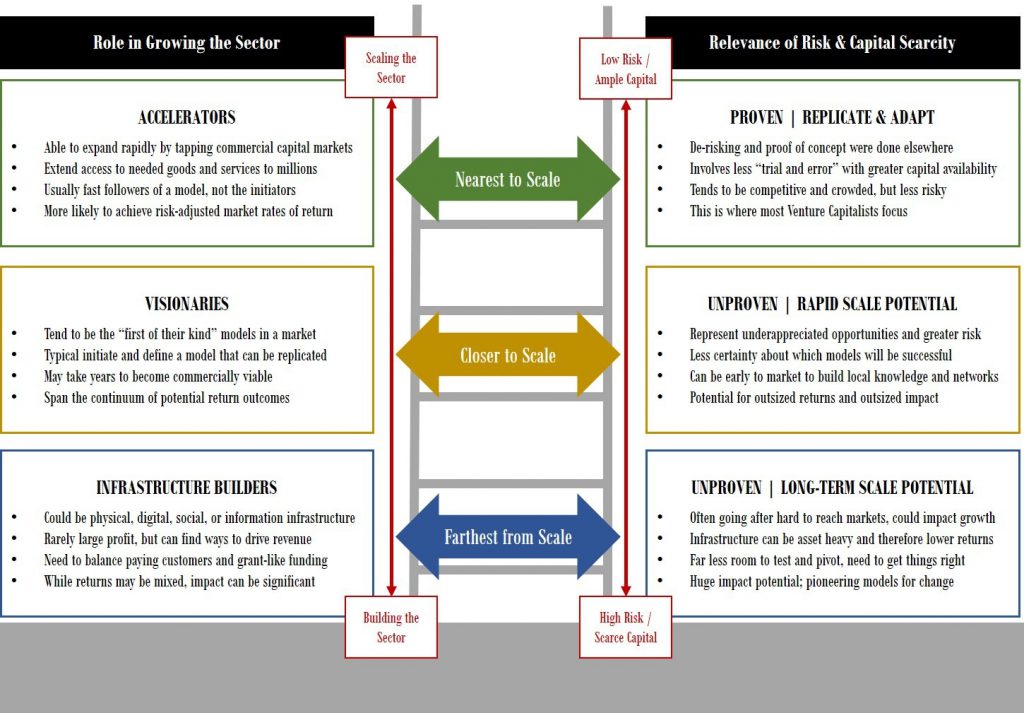

With a proper foundation in place and a thorough assessment of the ladder completed, the next step is to determine how much further the enterprise needs to climb. The goal is to determine how far from the top (transformational change) the enterprise is and what its journey to scale may be like. This is driven by where the enterprise sits along a continuum of two key considerations:

- The enterprise’s role in developing the market: those building market infrastructure versus those scaling an existing, proven model.

- The relative risk and capital scarcity related to that model: those lower on the ladder are riskier and thus less capital is available to support scale.

Within the context of first consideration there are three categories of enterprises according to their impact in growing an industry sector.

- Accelerators: enterprises that enter a after a visionary model has been proven and accelerate the growth of a sector by scaling their individual firms as they refine and improve upon the visionary model that served as their foundation – closest to the top.

- Visionaries: pioneering enterprises that believe in a product or service well before it is proven; they contribute to the sector by testing, validating, and proving the generic model of an innovation or product – in the middle.

- Infrastructure Builders: enterprises that advance a sector by addressing the common needs of industry players, thus helping to build a supportive ecosystem for future innovations to be built upon – farthest from the top.

Within the context of the second consideration there are another three categories of enterprises according to the relative risk and capital scarcity that correspond to the business model.

- Proven | Replicate & Adapt: enterprises leveraging proven models; this is where the bulk of existing Venture Capital money flows – closest to the top.

- Unproven | Rapid Scale Potential: enterprises pursuing unproven models; typically are asset light and serve lower- and middle-income populations; represents under-tapped opportunity waiting to be unlocked through typical Venture Capital structures — in the middle.

- Unproven | Long-Term Scale Potential: enterprises pursuing unproven models that may be asset intensive, serve only lower income groups, and/or operate in countries with less developed capital markets; this segment requires investors to be more creative with their approach, but offer tremendous impact potential – farthest from the top.

Each category above aligns across the ladder (i.e., “Infrastructure Builders” tend to be in the “Unproven | Long-Term Scale Potential” category as it relates to potential risk and capital scarcity). Steps 1 and 2 help an enterprise identify where it sits in these categories. Then, knowing which of these categories the enterprise is in helps assess one of the most significant hurdles to scaling social innovation: capital availability. Figure 6 below shows how these various categories align across the ladder and highlights the key characteristics of each category identified above.

Figure 6: Finding the Position on the Ladder

Figure 6: Finding the Position on the Ladder

After determining the gap to the top, the enterprise has a better idea of their role in building a market and how that relates to potential risk and capital availability. Knowing this is not only important for building a market driven scale strategy, but it is also important in identifying and establishing the appropriate partnerships and identifying the appropriate investors.

Step 4: Find Ladder Holders.

Pinpoint potential partners from private, public, and social sectors, particularly channel partners (distribution and sales channels) and finance partners.

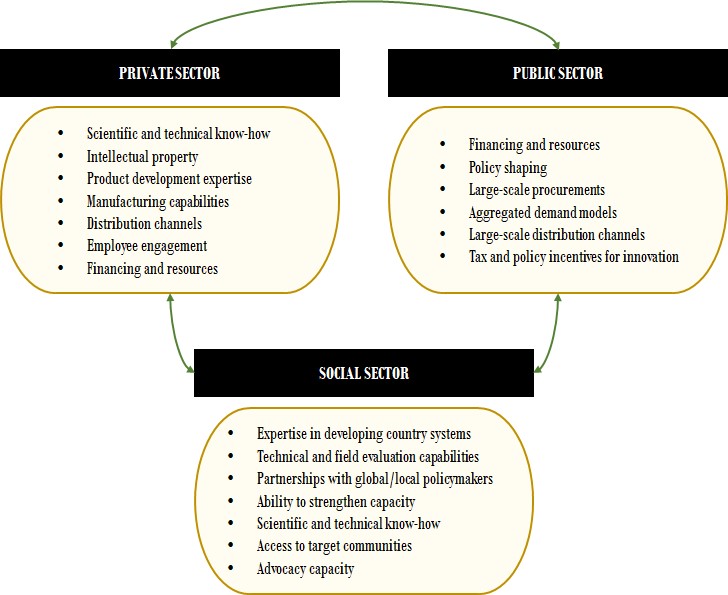

No ladder should be climbed without someone to hold and stabilize it. The same is true for the social innovation ladder. Very rarely can a social innovation enterprise achieve transformational change and sustain its impact without the expertise and the resources of partners from across the public, private, and social sectors.

At this stage, we have established the change the enterprise is trying to achieve at scale (its PMV), determined the unique environmental challenges that will be encountered, evaluated the specific attributes of the product-service that will support scale, and identified the enterprise’s role in developing a market and, thus, its corresponding risk and capital availability.

Scalable social innovations should be built to leverage partner resources as needed and will certainly vary depending on the issue they are addressing, the environment they are operating within, and other local conditions relevant to the enterprise. Figure 7 has been replicated and adapted from this article and outlines the potential contributions that could come from each sector. The Environmental Canvas and Product-Service Canvas should inform which contributions may be most valuable at any given time.

Figure 7: Examples of Partner Contributions

When an enterprise is determining which partners to engage, we think it is particularly important to spend time identifying potential sales and distribution channel partners, particularly those with local knowledge and experience, and engaging appropriately aligned capital partners.

Using partner channels for distribution may lead to lower margins but can also allow an enterprise to expand its reach more quickly. More importantly, the enterprise will be able to avoid the significant capital expense of establishing a new distribution network on its own.

When it comes to capital partners, it is important to identify capital that aligns more appropriately with the scale strategy and model of the enterprise. This often means eschewing traditional philanthropy and venture capital approaches for new structures. Below we highlight two investment structures that can be particularly amenable to social enterprises:

| Structure | Overview |

| Revenue-based financing (“RBF”) with structured exits | ● Investor gets paid a percentage of company’s revenue ● Revenue percentage is typically in the 4-5 percent range ● Investor return varies with company performance ● Valuable in markets where exits may be difficult ● Payments continue until investment is repaid up to an agreed upon multiple, typically 2.0 – 3.0 times the investment amount ● Typically positions investor as a lender rather than a shareholder or equity holder ● Unlike debt though, founders and managers generally do not have to guarantee the debt, despite lack of collateral ● Expect pay back in a few years, but not legally mandated |

| Demand dividends and similar variations | ● Tend to be specific to social enterprises ● Similar to RBF, valuable in markets where exit is difficult ● More of a debt instrument with some equity-like aspects ● Investor receives a temporary ownership stake as a preferred equity shareholder ● Payments to investor are deferred for 10 – 24 months ● After “holiday period” investor begins collecting dividends which are paid as a percentage of free cash flow ● Similar to RBF, these are variable payments but not paid as part of revenue, rather than as a percentage of profits ● Caps upside at a certain return on investment, at which time investor is no longer a shareholder ● Typically, must be paid in full within 7 years |

Additional alternative venture financing structures include venture debt, light preferred equity structures, prepayments enabled by crowdfunding, SAFE agreements, and even digital currency enabled structures. The world of venture financing is rapidly changing and adapting, and these new structures will continue to need new attention and research. Nonetheless, it is important to highlight these new structures as they may align more closely with a social enterprise’s long-term goals and strategies for scaling towards transformational change.

Now, with a holistic picture of the enterprise’s readiness and ability to scale, recognition of the enterprise’s role in developing the market and the potential capital availability, and the identification of appropriately aligned partners and investors, it is time to develop an appropriate strategy and execute.

Step 5: Extend the Ladder and Climb.

Establish milestones, develop strategies that move towards transformational change, and execute (return to step 1 and repeat as needed).

This final step of the process incorporates all the various learnings from the steps above. The goal is to establish milestones (extending the ladder) and build strategies that will guide the enterprise’s climb towards transformational change. As you will see below, these strategies can vary across different dimensions of what it means to “scale” and different levels within each dimension.

We do not presume to make prescriptions of the milestones an enterprise should establish. Instead, milestones should be developed by the management team of the enterprise in conjunction with its partners and investors. However, we note that any milestone developed should reflect key learnings from steps 1-4, should be time bound (short, medium, and long-term milestones), should include specific goals related to the up, out, or down scale dynamics the enterprise intends to address (discussed further below), and should cover and cross within each dimension and level of potential scale (discussed further below).

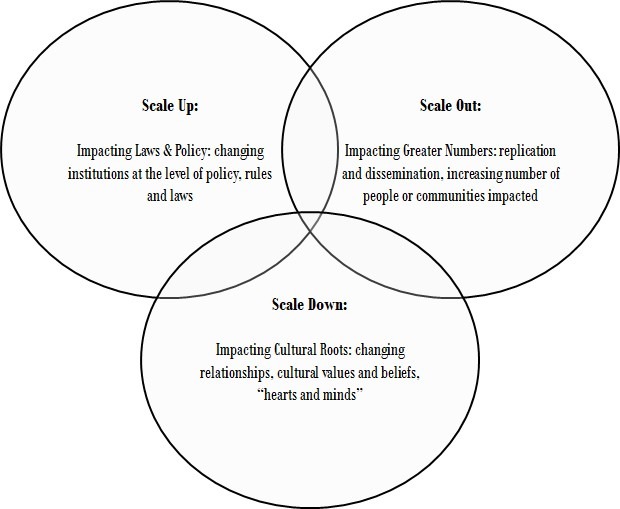

In order to truly achieve transformational change (the kind of change that shifts entire systems) an enterprise needs to think about scale within three categories: (1) scaling up – influencing policy, (2) scaling out – replicating and adapting, and (3) scaling down – influencing culture (see Figure 8 – replicated and adapted from this research). This means moving beyond the simple concept of scaling through replication and dissemination and developing a strategy that reflects a combination of these three approaches.

Following Moore et al, scaling up relates to strategies that aim to change institutions at the level of policy, rules and laws. Scaling out relates to strategies that aim to replicate and disseminate the innovation, increasing the number of people or communities impacted. Scaling down relates to impacting cultural roots by changing relationships and/or cultural values and beliefs (a “hearts and minds” strategy). Typically, organizations will move from scaling out to scaling up, scaling out to scaling down, or some similar combination, but usually not immediately to scaling up or down. By combining these categories of scaling, large systems change can be achieved.

Figure 8: Scale Up, Scale Out, Scale Down

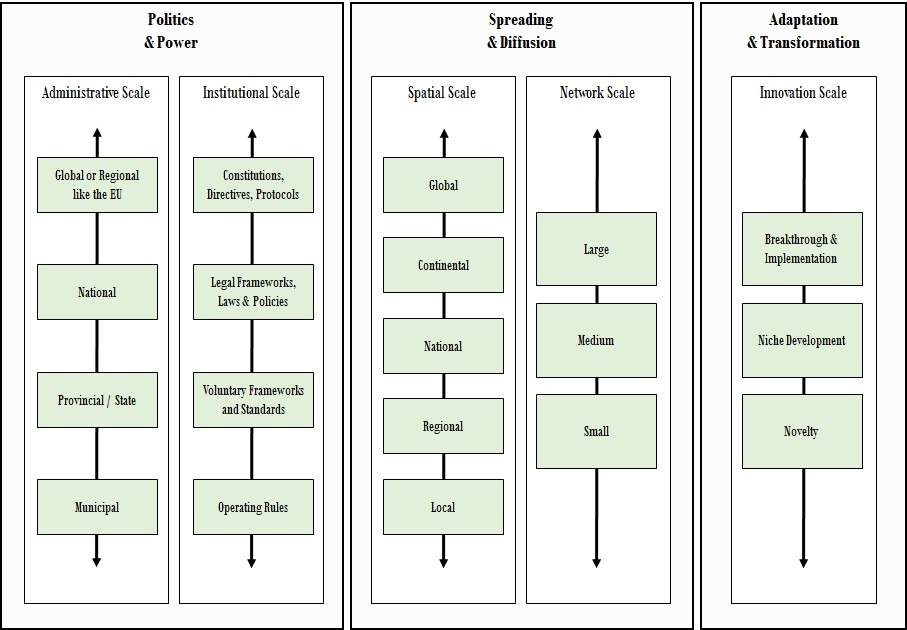

Understanding these three categories of scale implies movement across a variety of different dimensions and levels: (1) a “politics and power’ dimension with an administrative scale and an institutional scale within it, (2) a “spreading and diffusion” with a spatial/geographic scale and a network scale within it, and (3) an “adaptation and transformation” dimension with an innovation scale within it. Figure 9 — replicated and adapted from this research — provides a visualization of these three dimensions for scale and the levels of scale within each one.

Figure 9: Dimensions, Scales, and Levels for Scaling Social Innovation

Figure 9: Dimensions, Scales, and Levels for Scaling Social Innovation

An enterprise looking to “scale up” would be navigating an administrative and institutional scale ranging from local to global government structures as well as operating rules to full constitutions. An enterprise “scaling out” would be navigating a spreading and diffusion dimension targeting geographic proliferation from local communities to global ones as well as a network scale dictated by the number of people impacted ranging from small to large. Lastly, an enterprise scaling through the innovation cycle will focus on moving from a novelty level innovation to a true breakthrough innovation which is then followed by implementation. Thus, a well thought out and integrated scale strategy will combine and cut across these dimensions in a way that involves movement up each level of scale and movement across and between dimensions.

Once the enterprise has developed its strategy and established its milestones it should begin to execute against that strategy (i.e., begin the climb). When the time comes that the enterprise has achieved its climb (i.e., successfully executed its strategy), or, more importantly, as the environment and the organization evolve over time, it should revisit step 1 of the framework to begin the process over again. This iterative process will allow the enterprise to adapt its strategy, discover any changes or pivots that may be required, identify new partners as needed, build new strategies, and develop new milestones that together will allow the enterprise continue climbing the ladder towards the transformational change they set out to achieve.

Conclusion

We believe that establishing a more holistic framework for evaluating a social innovation’s readiness for scale and establishing strategies to scale will help move the ecosystem towards the transformational change it intends to create more quickly. It will also allow for more rapid social innovation development and better coordination between innovators, funders, and other actors as they seek to scale.

Using the analogy of climbing a ladder conceptualizes the framework and the five step, iterative process it prescribes. By inspecting the foundation (assessing the purpose, mission, and vision of the enterprise in the context of whether or not the external environment is more or less supportive of scale), assessing the ladder (evaluating the internal product-service attributes to determine ease of scale), determining the gap (determining where the enterprise sits along the continuum of sector impact and risk/capital scarcity), finding ladder holders (identifying appropriate partners across the public, private, and social sectors), and extending the ladder and climbing (establishing strategies and milestones for scale based on the learnings from steps 1-4) the social innovation ecosystem will be better aligned around what to scale and how to scale it.

As more and more social entrepreneurs implement and repeat this process, more and more innovations will achieve the large-scale, transformational change we hope to see in the world.